Health professionals have spent years trying to pinpoint the sources of America’s rising obesity levels, but research by University of Virginia Professor Christopher Ruhm suggests it might be time to look beyond the usual suspects.

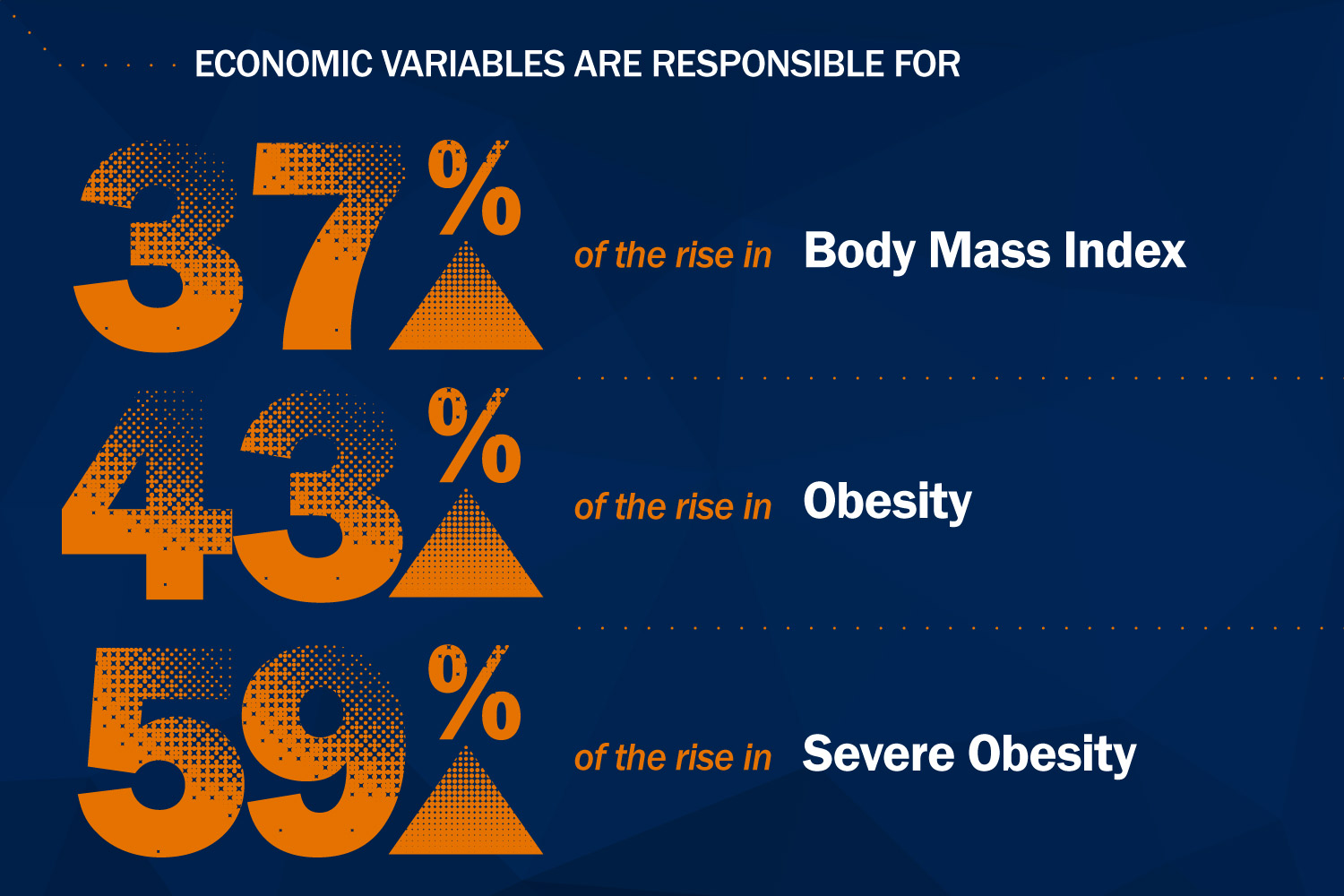

Ruhm, a professor of public policy and economics in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, recently completed a joint research project examining the economic factors that can lead to obesity. It revealed that collectively, economic variables explain 37 percent of the rise in body mass index or BMI, 43 percent of the rise in obesity and 59 percent of the rise in Class II and III obesity – extreme obesity defined by a BMI of 35 or higher.

The full study was done in collaboration with economics professors Charles Courtemanche, Joshua Pinkston and George Wehby of Georgia State University and the findings were published in the spring edition of the Southern Economic Journal.

Christopher Ruhm is a professor of public policy and economics in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. (Photo by Dan Addison)

“There’s been a very rapid rise in obesity in last three decades but we don’t fully understand what the causes are,” said Ruhm. “Here, we were attempting to do a more integrated study that looked at a larger variety of potential causes.”

The Centers for Disease Control estimate that approximately one-third of all American adults are obese today, a massive jump from the mere 13 percent in 1960.

“Our research looks at 27 different factors, basically measuring anything that’s been in economic literature as a potential cause,” said Ruhm.

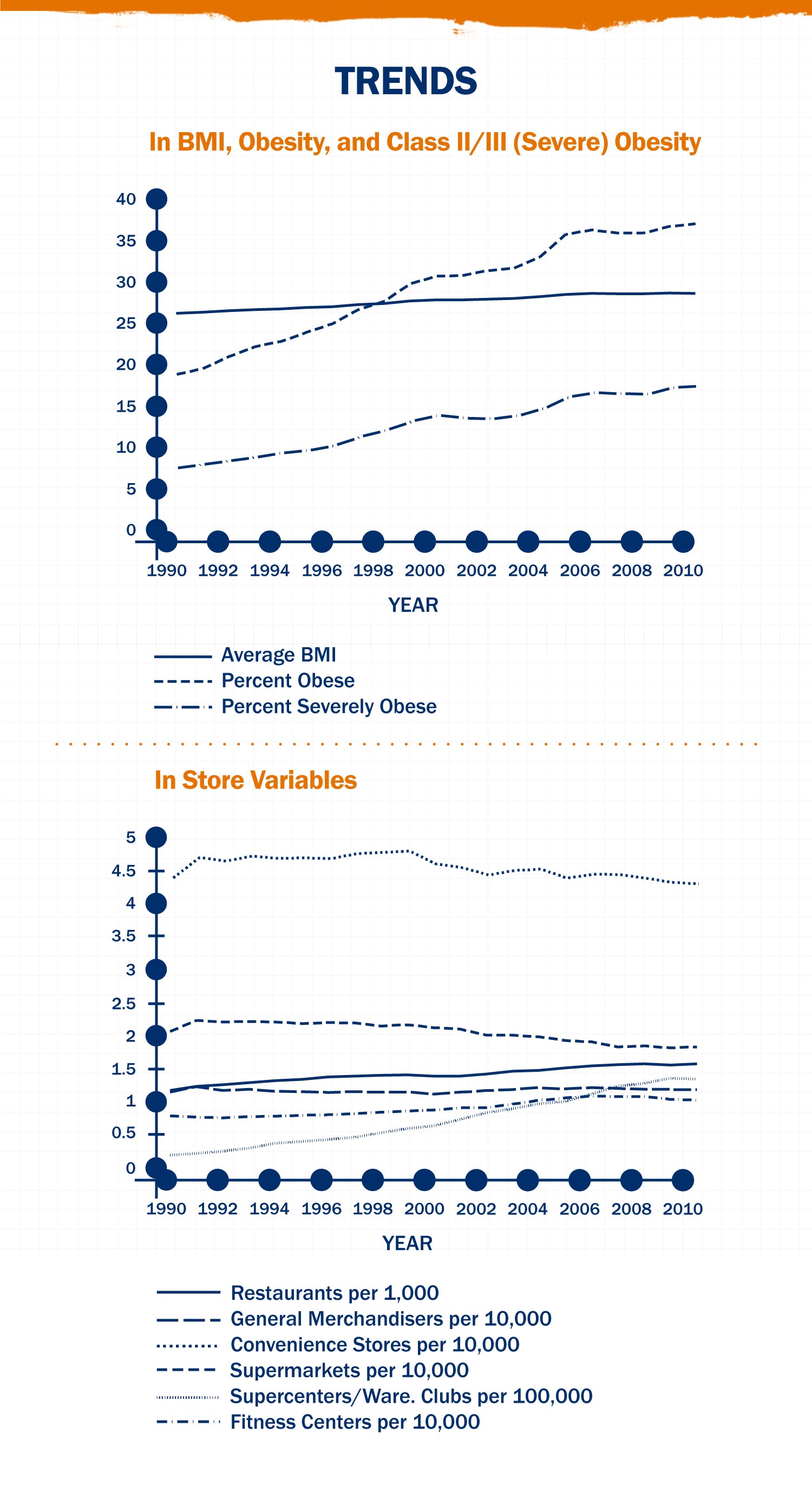

Using survey data from around the country, he and his fellow researchers examined the impact of variables like big box grocery stores and restaurants per capita, the proportion of the work force in blue collar jobs and the prices of alcohol, food and cigarettes.

Among all these factors, the number of restaurants per capita and the number of supercenters and warehouse clubs per capita had the most statistically significant impact on rates of obesity. Populations with access to more restaurants and big box stores tended to have higher rates of obesity.

Ruhm said it’s unclear exactly why these factors have the biggest impact, but he has some theories.

“My own view is that restaurants and supercenters are essentially lowering the prices and making all kinds of food more available, but particularly calorie dense food,” he said. “If you go into a supercenter, you could buy healthy food but there’s also a lot of unhealthy food that you can buy cheaply and in large quantities.”

He went on to explain that while having lots of restaurants available may not lower the monetary cost of eating out, it can still incentivize people towards making poor eating choices by lowering the time cost. Having access to faster, more efficient meal options means less time invested in meal preparation.

In addition to studying economic factors that directly contributed to weight gain, the researchers also looked at weight loss attempts as a way to measure the population’s own cost-benefit assessment of weight gain.

“There are some economic models that argue that when we see higher weight, typically what we’re seeing is just a rational or optimal decision because it’s become cheaper or more enjoyable to eat more,” said Ruhm. “But we view the weight loss attempts as an indication that people are overeating from their own perspective. They’re feeling like they’ve made an error.”

Looking back at the economic factors that are the biggest contributors to poor dietary decisions, the researchers agree that limiting the number of superstores and restaurants per capita is both an unrealistic and undesirable solution. Instead, Ruhm suggests that policymakers implement small incentives for people to select healthy foods. Specifically he proposes higher subsidies for fresh fruits and vegetables that will be sold as such over subsidies for the various components of processed foods.

“There’s also a whole other set of interventions that people refer to as ‘nudges.’ That’s when you try to create small costs to making bad decisions for your health,” he said.

For example, placing healthier dessert choices like fruit closer to the front and high calorie choices like cake towards the back in cafeterias and buffets creates a small “nudge” for people to choose the low calorie option. When there’s a line waiting behind you, the time cost is lower for the closest foods.

Ruhm and his fellow researchers will soon have a better idea of the kind of policy nudges that are most effective in promoting healthy choices. Now that they’ve studied outside economic factors that impact weight gain, they plan to take a closer look at decision-making on an individual level.

“We’re doing a little bit of work trying to understand the extent to which these eating decisions are rational, that people are balancing costs and benefits versus the extent to which they’re impulsive decisions,” he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 2, 2016

/content/supercenters-may-be-supersizing-americans