A new exhibition at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections sheds light on an often-overlooked Harlem Renaissance poet in UVA’s backyard.

The exhibition, titled “Anne Spencer: I Am Here!” showcases the life and work of Lynchburg poet Anne Spencer. She was known for her poetry on the natural world, her civil rights advocacy and her elaborate garden. Spencer may not be as well-known as her contemporaries, but she was influential, becoming one of the first Black woman whose works were included in the “Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry.” Though she spent most of her life in Virginia, she played a critical role in the Harlem Renaissance after visits from James Weldon Johnson and other movement figures.

Though just as important as contemporaries like Langston Hughes, Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer is less-known to the general public. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

“This is such an exciting way to introduce her to the public, since she didn’t get all the credit she deserved,” said Tessa Berman, a fourth-year student who co-curated the exhibition’s poetry section.

“Anne Spencer: I Am Here!” opens Tuesday and runs through June 14. It’s the final chapter in a three-part series at Special Collections examining Black history in Central Virginia a century ago. The first chapter focused on the Holsinger Studio, a rare example of a photography studio that photographed Black people as they chose to present themselves. The exhibit earned praise from outlets like the Washington Post and PBS. The second exhibit drew upon Special Collections’ significant selection of music, monographs and more from the Harlem Renaissance.

The current exhibition, a partnership between UVA Library and the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum, offers a comprehensive view of Spencer’s poetry, activism and domestic life – which often intertwined, as she sometimes wrote on the walls of her Lynchburg home.

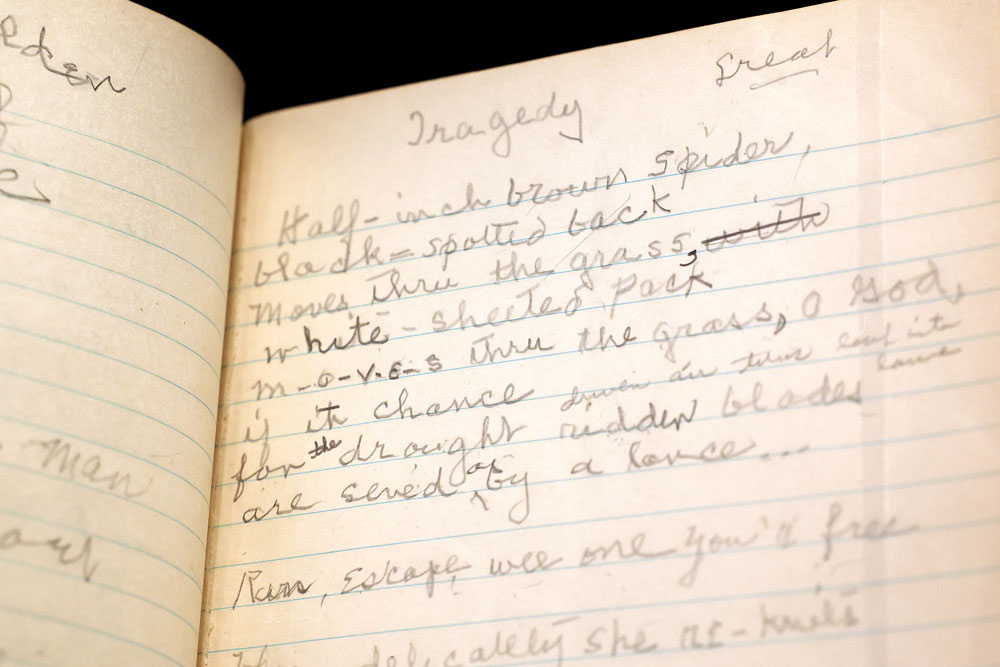

Spencer didn’t just write in notebooks – she’d scrawl poems on bills and the walls of her home. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Spencer wrote on every available surface, from electric bills to Christmas cards. Consequently, the exhibition is “fragmentary in nature,” according to curator Holly Robertson. The exhibition’s items range from published poetry to her husband’s business ledgers (the Spencers were landlords and developed properties in a Black Lynchburg neighborhood, where many of the houses still stand). In addition to manuscripts, photographs and a replica of Spencer’s personal library, the exhibition includes a still-unpublished poem. The love poem, written on Spencer’s copy of “Dreer’s Garden Book,” celebrates her joy of being able to love, even if she can do little else.

“She was often criticized for not being political, for writing feminine poetry about flowers,” said Jacquelyn Kim, the exhibitions coordinator with UVA Library who curated the exhibition’s section on Spencer’s civil rights activism. “But she was really very political.”

Civil rights leaders first encouraged Spencer to publish her poetry. NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson visited her in 1919 (Spencer was an early member of the organization’s Lynchburg chapter in 1913) and pushed her to publish her work. An earlier visit from Langston Hughes likewise inspired her poetic pursuits.

The exhibition is the result of a partnership with the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Countee Cullen, a fellow poet, was also a friend. Spencer – despite what critics said – wrote her biographical note to Cullen’s poetry anthology, describing the difficulties of being a Black woman. “By hell, there is nothing you can do that you want to do – and by heaven you are going to do it anyhow,” Spencer wrote.

When writers, artists and activists involved in the Harlem Renaissance traveled through the South, they would often stay with Spencer.

“The Harlem Renaissance came to Anne Spencer,” Robertson said.

The Spencer house was a safe place to stay for traveling Black intellectuals in a segregated South. W.E.B. Du Bois, for example, needed a place to stay where he could bathe – most Southern hotels would not allow him to use their bathrooms.