The growing numbers of students living off Grounds contributed to soaring rents citywide. Between 2012 and 2018, the average apartment rents rose 18.1%, jumping by 9.4% in 2017 alone. Among the major apartment buildings in the Charlottesville market, average rents were $1,384. This, as one report on the city’s housing needs noted, means that “a single person working a minimum-wage job would need to work 147 hours per week” to be able to afford to live in the city. A person earning $15 an hour (the new living wage standard adopted in January 2020 by the University) would still need to work 71 hours per week to be able to afford the average apartment in Charlottesville. At 40 hours a week, individuals earning $15 an hour would spend over half their income on housing. That same report found a deficit of 3,318 affordable housing units in Charlottesville for 2017, projected to reach 4,020 by 2040. The latter figure parallels that of UVA’s off-Grounds enrollment growth since 2000: 3,920 students.5

The growing cost of living in Charlottesville is, in one sense, indicative of the city’s prosperity. But the benefits, as well as the burdens, of economic growth have been unevenly distributed, and too often come at the expense of Charlottesville’s Black residents. Between 2010 and 2017, white median household income in Charlottesville rose from $45,000 to $64,000, inflation adjusted. Meanwhile, African American median household income actually fell from $31,000 to $28,000. Over the past two decades, the city’s African American population has declined from 22% to 18.4% of the city’s total population.

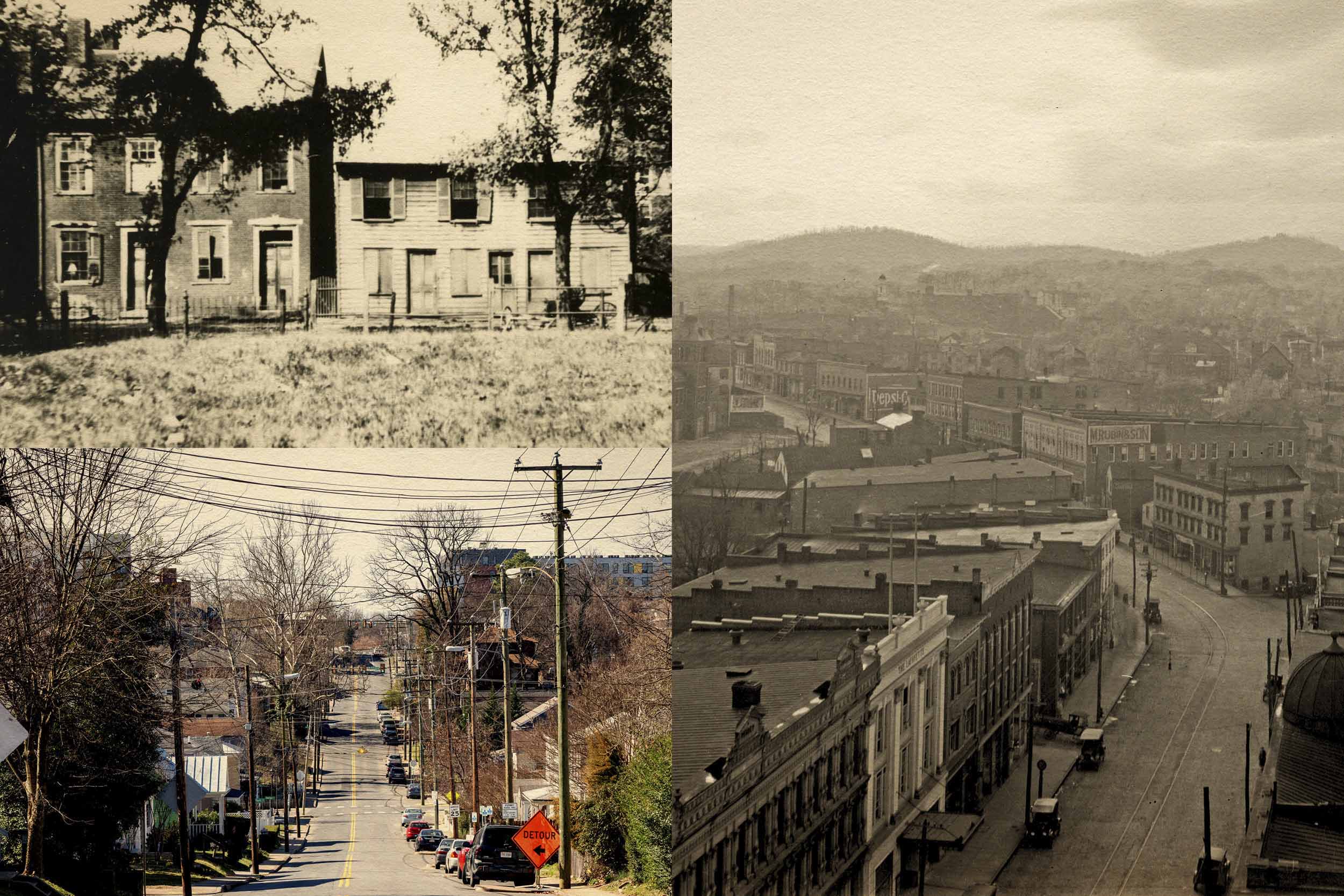

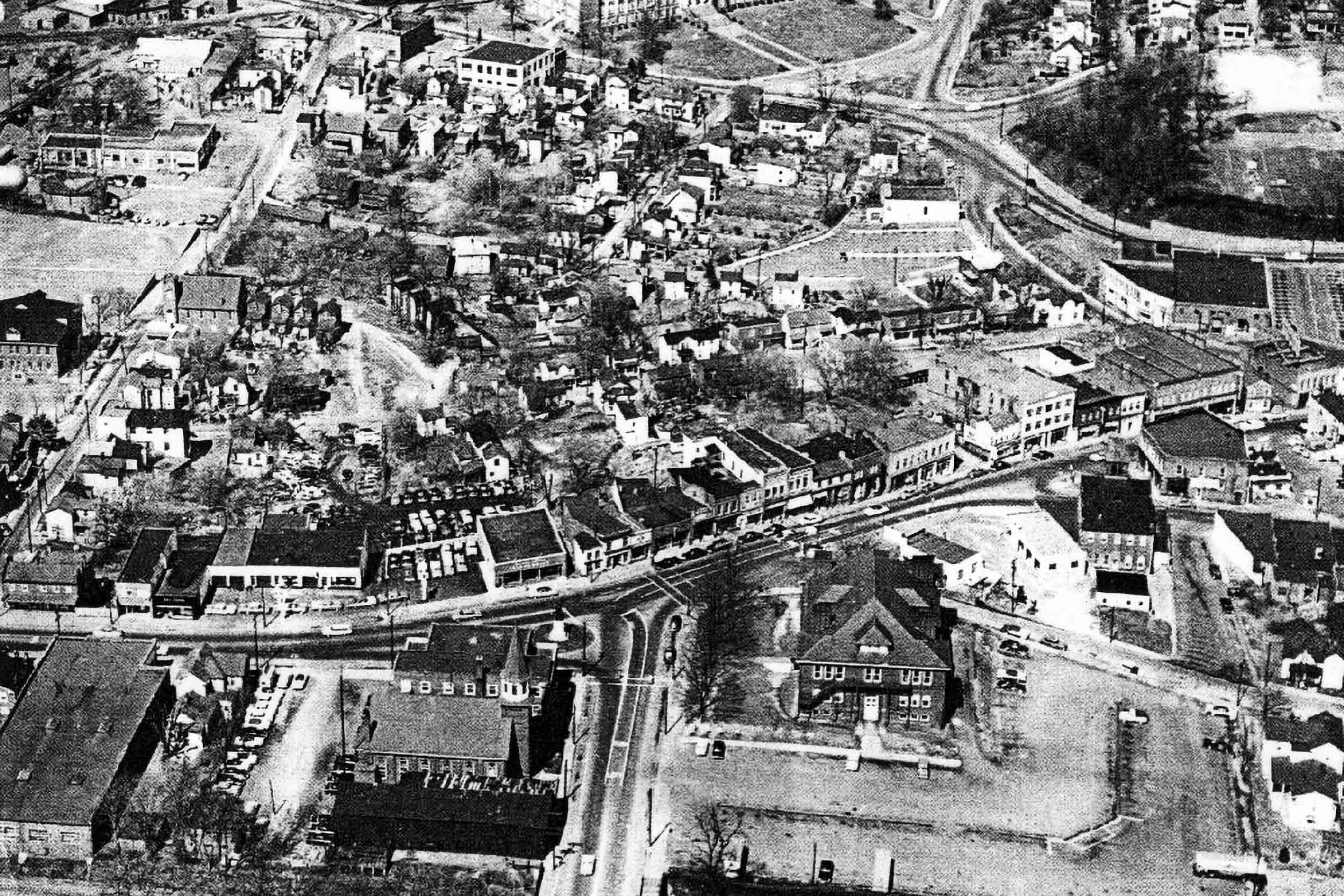

These changes have been especially pronounced in the neighborhoods surrounding the University. In the 10th and Page neighborhood, the African American population dropped 17 percentage points between 2010 and 2017, from 72% to 55%. Simultaneously, median rent in this neighborhood rose from $666 to $939, median home value increased from $160,300 to $205,800, and overall median household income rose from $17,000 to $38,000. The dwindling number of longtime residents who remain bemoan the loss of community that has accompanied the area’s changing racial and socioeconomic demographics, a transformation embodied in the proliferation of fences and walls around properties and new businesses catering to the consumer tastes (and pocketbooks) of students and young white professionals.6