Editor’s note: Even an institution as historic as the University of Virginia has stories yet to be told. Some are inspiring, while the truths of others are painful, but necessary for a fuller accounting of the past. As Baptist minister and former Southern Christian Leadership Council leader Fred Shuttlesworth once said, “If you don’t tell it like it was, it can never be as it ought to be.”

The president’s commissions on Slavery and on the University in the Age of Segregation were established to find and tell those stories. “UVA and the History of Race” – a joint project of UVA Today, the president’s commissions, and faculty members and researchers – presents some of them, written by those who did the research. The project reflects UVA’s educational mission and the commission’s charge to educate, and to support the institution as a living laboratory of learning.

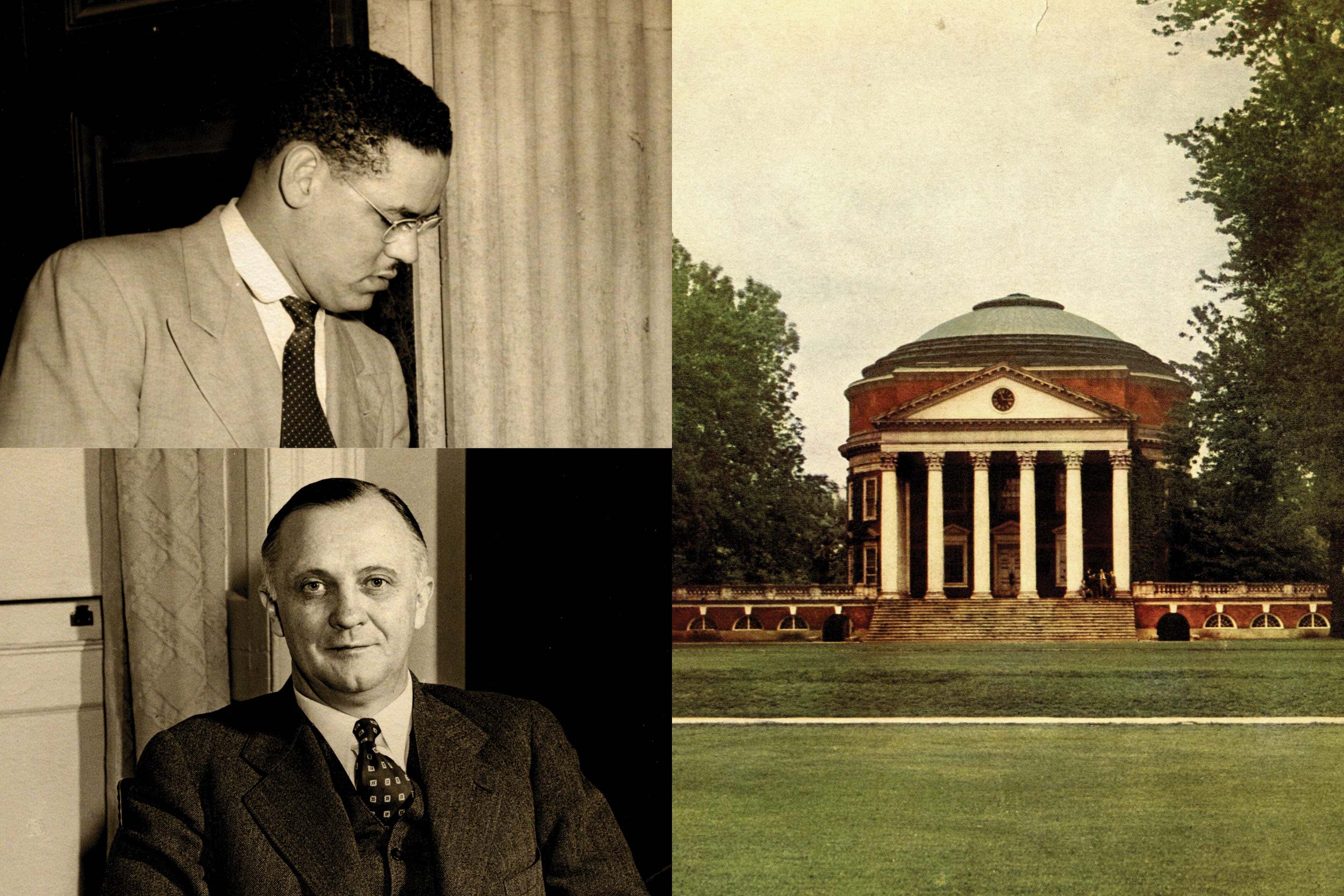

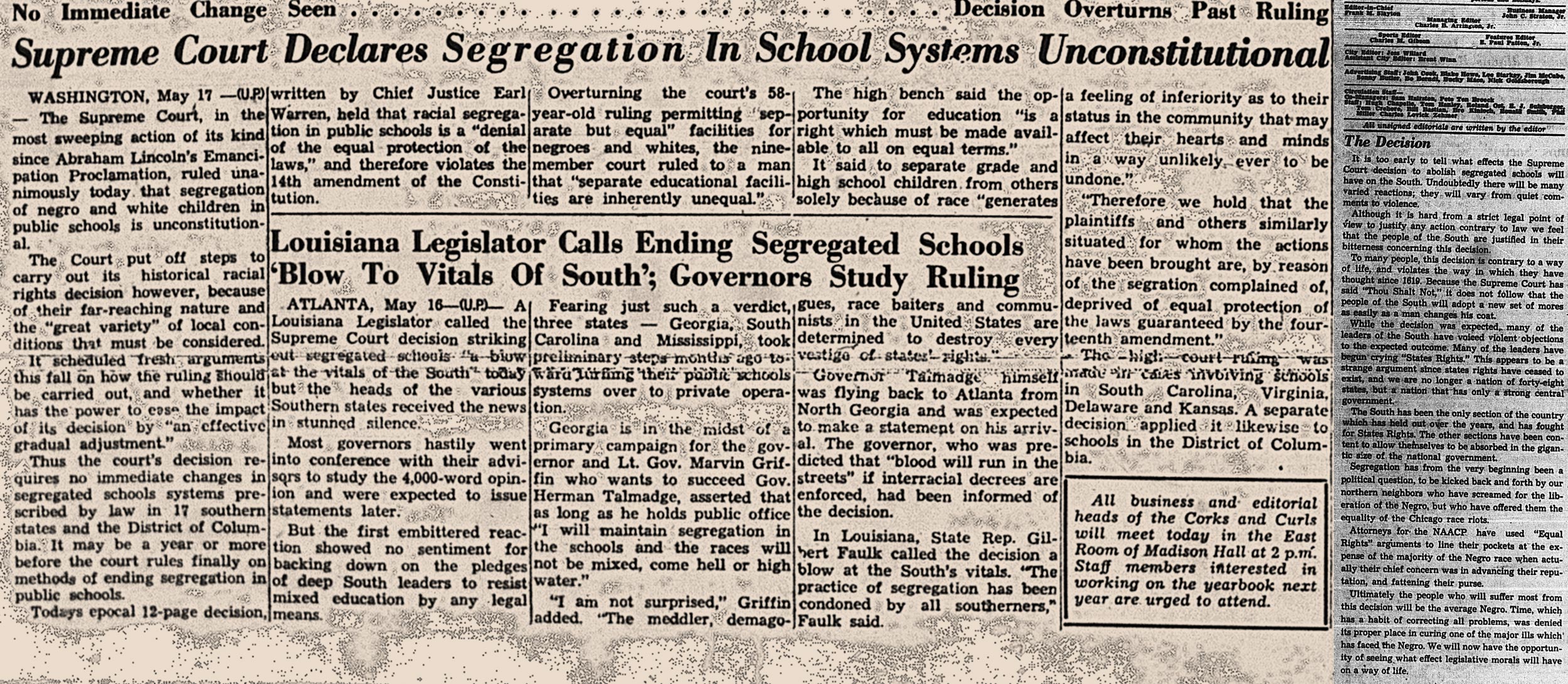

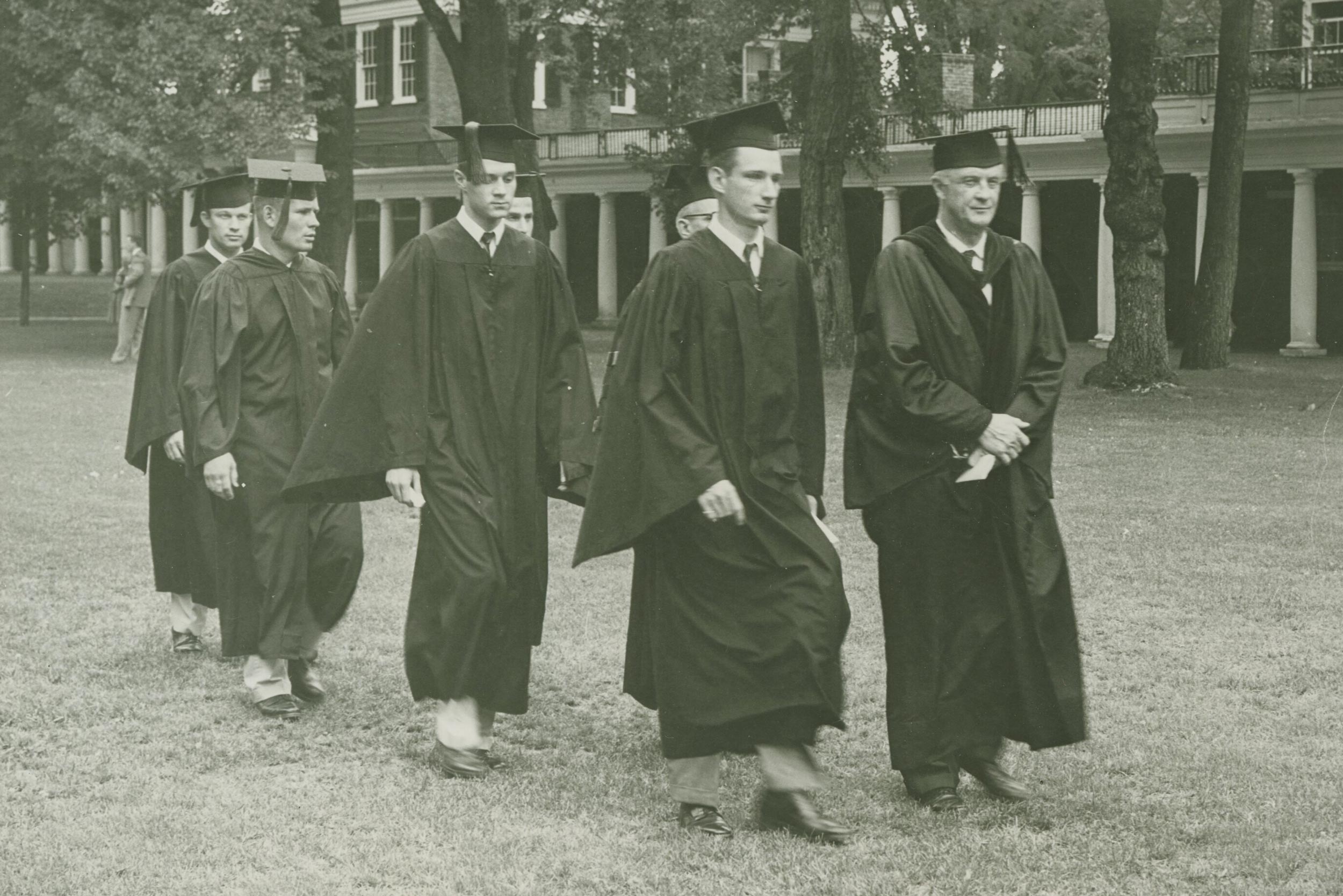

Today’s story, “Winds of Change in the 1950s,” commences the second half of the series, which includes six installments to be published in March, exploring topics primarily ranging across UVA during the 20th century. Topics included in the second half of the series include:

- Momentum for a more inclusive University in the 1950s.

- The UVA experience for Asians and Asian Americans.

- Gentrification’s impact on African American communities.

- Segregation’s legacy in the UVA hospital.

- UVA in the era of Massive Resistance.

- The University’s allies in integrating Virginia public schools.

Find all of the stories published to date at UVA Today.