October 7, 2008 — This summer, when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its historic affirmation of the right of detainees at Guantánamo Bay to challenge their confinement, one University of Virginia history professor’s research was critical to how the justices arrived at their decision.

For nearly a decade, Paul Halliday, associate professor of history, has been quietly studying the use of habeas corpus in England and its empire back to the 16th century and earlier. Habeas corpus, the judicial means by which prisoners may demand that their jailer show a valid reason for their detention, is considered a bedrock of personal liberty in U.S. law — and is the only specific right enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

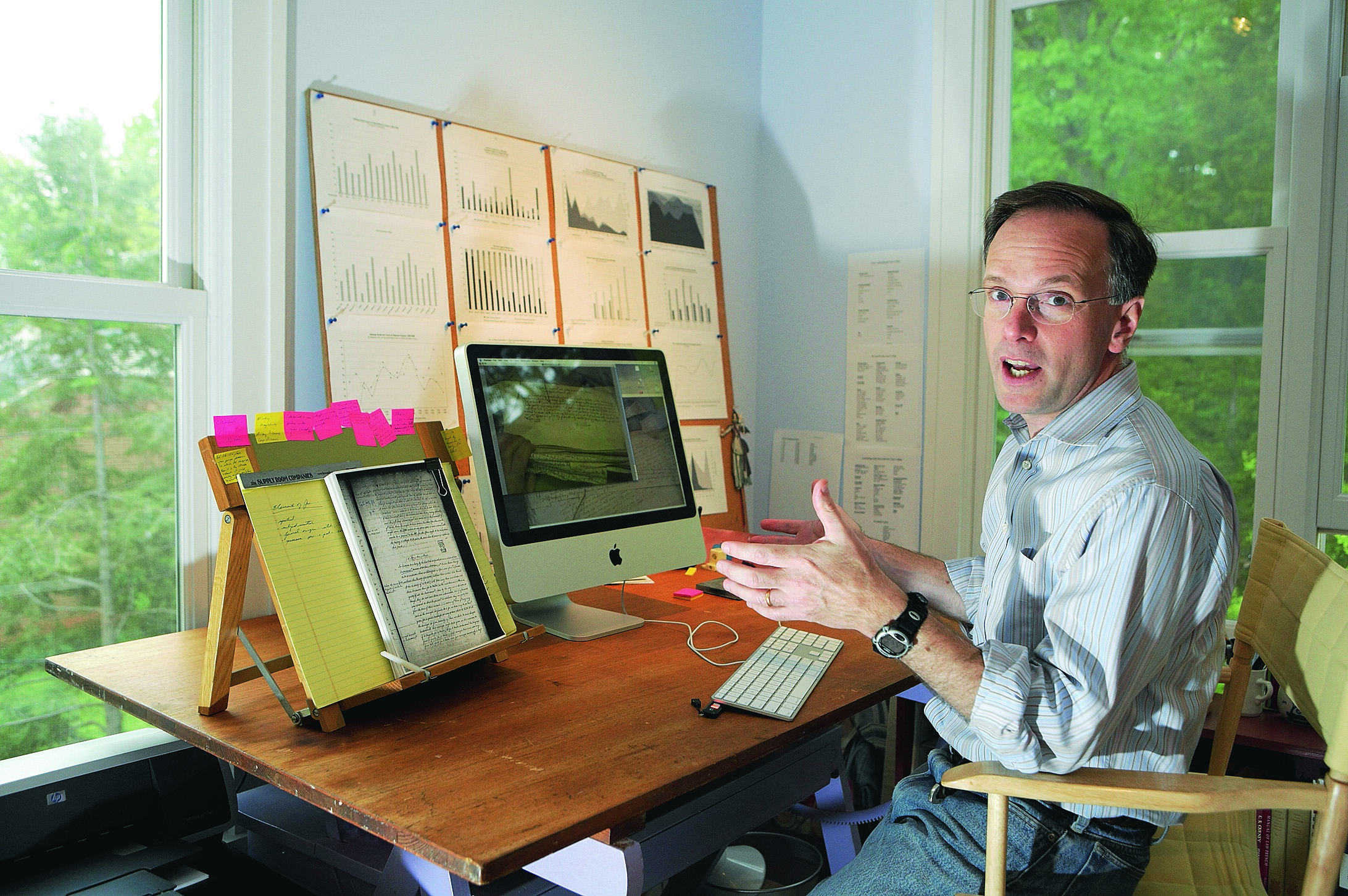

“Like most historians, I like to think of my work as leading to reconceptions of a problem, allowing us to see more fully what the law was and how it was conceived and used,” Halliday said.

“Paul is probably the most knowledgeable person on the planet about the historical scope of the writ of habeas corpus and its use in the Anglo-American tradition,” said James Oldham, St. Thomas More Professor of Law and Legal History at Georgetown University Law Center, who consulted with Halliday about the writ’s history for several amicus briefs written on behalf of the Guantánamo detainees. Halliday’s book on the subject (expected in 2010) “will rewrite that history [of habeas corpus] in a fundamental way,” Oldham said.

Seeing More Fully

Halliday never dreamed he would be doing research on habeas corpus because so much had already been written about it. But while immersed in research on the role of litigation in 16th- and 17th-century English politics at London’s National Archives, Halliday realized that documents concerning more than 11,000 habeas cases from the court of the King’s Bench — the king’s greatest common law court — remained bundled in their original files, most unopened since they were stored away hundreds of years ago.

It turns out, he said, that the many volumes written about the “Great Writ” are “astonishingly superficial,” based on printed case reports that amount to less than 2 percent of the thousands of writs answered by justices of the peace and all kinds of other magistrates across England and the empire in cases ranging from family disputes to slavery.

Halliday began spending his summer and semester breaks in the National Archives at Kew, Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the British Library and university and law school libraries at Cambridge, Yale and Harvard.

“The more work I did, I realized that what’s in the archive and what’s been written [about habeas corpus] had nothing to do with one another,” he said.

Scribbled on tiny scraps of parchment (1 or 2 inches by 8 to 10 inches) and written in Latin, many writs are rumpled, worm-eaten and soiled with coal dust, dirt or water stains. Halliday has photographed thousands and noted their contents, which he then analyzes in an intricate computer database that tracks each case.

“The writ of habeas corpus was not founded on ideas about liberty,” he was surprised to learn. Instead, it was designed to ensure that individuals imprisoning people in the king’s name upheld the law and did not abuse their authority.

“The focus of habeas corpus was on the wrongs of jailers rather than the rights of prisoners,” Halliday said. “Judges were concerned with the behavior of jailers and that they acted within the law.” Paradoxically, this would give the writ its great strength as ideas about liberty developed outside of law.

This was clear in 1605, when jailer Francis Hunnyngs repeatedly refused to return habeas writs granted by the court of King’s Bench on behalf of people imprisoned in a property dispute. Ultimately, the court found Hunnyngs in contempt, and he went to jail.

“When they jailed the jailer,” Halliday said, “we can see how determined the court was to ensure that everybody who claimed to act in the king’s name answered to the judges.” From these beginnings, a kind of judicial authority developed that would make it possible to use habeas corpus to protect what we later came to know as civil liberties.

The relationship of the king to his subjects — which included aliens living within the king’s protection — was considered a bond of reciprocity, Halliday explained: “The king protects the subject, and the subject protects the king, literally, with his body.” (The Latin habeas corpus is sometimes translated as “produce the body.”) It was in the king’s best interest to ensure that his jailer, as the king’s authority, acted within the bounds of the law, whenever the body of any subject was detained.

Guantánamo and the Supreme Court

The key in the Supreme Court Guantánamo case (Boumediene v. Bush) was whether noncitizens are entitled to habeas corpus, and if so, whether they must be on American soil to use it. A recent Virginia Law Review article by Halliday and U.Va. Law School’s American legal historian G. Edward White — not yet published when sought out by the Court — was cited four times in the decision and by attorneys on both sides.

Halliday and White identified what the Founding Fathers understood about habeas corpus and why they included the “Suspension Clause” in the Constitution, which reads: “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” Since 1789, the writ has been suspended only a few times, always controversially, including by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 allowing U.S. internment of people of Japanese descent.

The article also showed that the English court consistently allowed foreigners access to habeas corpus. In the 1640s, during the English Civil War, justices used habeas corpus to release those imprisoned by military officers. Between 1689 and 1710, Chief Justice Sir John Holt and his court released hundreds of accused traitors and spies — French, Irish, Scots and English — during wartime and threatened rebellion, while always identifying those who might, by law, rightly merit prosecution.

“Place was not the point in habeas litigation. People were,” Halliday writes.

“Paul’s work sheds light on the original meaning and purpose of the Constitution’s guarantee of habeas corpus,” said Jonathan Hafetz of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, who consulted with Halliday for an amicus brief in the Guantánamo cases. “It shows that efforts to deny habeas corpus to detainees today and to create prisons outside the law contradicts centuries of history and tradition.”

Still, Halliday cautioned, one thing not found in the past is the present, and looking for cases identical to today’s is not the way to use history. Neither is it right to superimpose one generation’s experience on another’s from hundreds of years before, for each lives in a “different mental universe.” Instead, he writes about how he, as a historian, looks at the evidence: “What we find in thousands of cases across thousands of miles are patterns revealing principles about habeas corpus.”

And that’s what it takes, he said. If the past is expected to inform current legal issues, legal and judicial practitioners must do much more serious work in court archives to detect trends and patterns in Anglo-American jurisprudence.

“I want my research to teach American lawyers and judges: Not so fast — don’t be so quick to think that by reading a handful of sources everyone has read over and over again that you can declare, ‘It was thus and such in the past, so we will do thus and such in the present.’ If judges are supposed to be informed by what happened in the past, they need to take much more seriously what it takes to recover that past.”

That kind of historical analysis, he said, “might help us think our way into the problems we confront today from surprising points of entry that we might not otherwise see.”

This approach to research also informs every course he teaches, encouraging his students’ questioning and critical analysis — the heart of the liberal arts education.

Images of writs of habeas corpus are provided courtesy of History professor Paul Halliday, who photographed them for his research purposes. Reproduced by permission from The National Archives, London, England.

The National Archives of the United Kingdom: Making Discoveries Possible

The writs are found at the National Archives of the United Kingdom. Many of the writs had not been viewed since they were tied and wrapped hundreds of years ago. Due to their fragility — imagine how dry and rigid parchment could be after centuries – the National Archives Conservation Department devoted many hours to softening and flattening the writs for Professor Halliday’s use, to his — and our — tremendous gratitude.

A visit to the National Archives Web site will provide this introduction to the revered British institution:

Who we are

The National Archives is a government department and an executive agency of the Secretary of State for Justice. It brings together the Public Record Office, Historical Manuscripts Commission, the Office of Public Sector Information and Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

What we do

The National Archives is at the heart of information policy, setting standards and supporting innovation in information and records management across the U.K., providing advice on opening up and encouraging the re-use of public sector information. Through our efforts in promoting best practice in information management, we look to ensure the survival of today´s information for the future.

The National Archives is also the U.K. government’s official archive, containing 900 years of history with records ranging from parchment and paper scrolls through to digital files and archived websites. The National Archives makes open records available to all, either onsite or online, continuously developing new tools to make history tangible for everyone.

For nearly a decade, Paul Halliday, associate professor of history, has been quietly studying the use of habeas corpus in England and its empire back to the 16th century and earlier. Habeas corpus, the judicial means by which prisoners may demand that their jailer show a valid reason for their detention, is considered a bedrock of personal liberty in U.S. law — and is the only specific right enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

“Like most historians, I like to think of my work as leading to reconceptions of a problem, allowing us to see more fully what the law was and how it was conceived and used,” Halliday said.

“Paul is probably the most knowledgeable person on the planet about the historical scope of the writ of habeas corpus and its use in the Anglo-American tradition,” said James Oldham, St. Thomas More Professor of Law and Legal History at Georgetown University Law Center, who consulted with Halliday about the writ’s history for several amicus briefs written on behalf of the Guantánamo detainees. Halliday’s book on the subject (expected in 2010) “will rewrite that history [of habeas corpus] in a fundamental way,” Oldham said.

Seeing More Fully

Halliday never dreamed he would be doing research on habeas corpus because so much had already been written about it. But while immersed in research on the role of litigation in 16th- and 17th-century English politics at London’s National Archives, Halliday realized that documents concerning more than 11,000 habeas cases from the court of the King’s Bench — the king’s greatest common law court — remained bundled in their original files, most unopened since they were stored away hundreds of years ago.

It turns out, he said, that the many volumes written about the “Great Writ” are “astonishingly superficial,” based on printed case reports that amount to less than 2 percent of the thousands of writs answered by justices of the peace and all kinds of other magistrates across England and the empire in cases ranging from family disputes to slavery.

Halliday began spending his summer and semester breaks in the National Archives at Kew, Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the British Library and university and law school libraries at Cambridge, Yale and Harvard.

“The more work I did, I realized that what’s in the archive and what’s been written [about habeas corpus] had nothing to do with one another,” he said.

Scribbled on tiny scraps of parchment (1 or 2 inches by 8 to 10 inches) and written in Latin, many writs are rumpled, worm-eaten and soiled with coal dust, dirt or water stains. Halliday has photographed thousands and noted their contents, which he then analyzes in an intricate computer database that tracks each case.

“The writ of habeas corpus was not founded on ideas about liberty,” he was surprised to learn. Instead, it was designed to ensure that individuals imprisoning people in the king’s name upheld the law and did not abuse their authority.

“The focus of habeas corpus was on the wrongs of jailers rather than the rights of prisoners,” Halliday said. “Judges were concerned with the behavior of jailers and that they acted within the law.” Paradoxically, this would give the writ its great strength as ideas about liberty developed outside of law.

This was clear in 1605, when jailer Francis Hunnyngs repeatedly refused to return habeas writs granted by the court of King’s Bench on behalf of people imprisoned in a property dispute. Ultimately, the court found Hunnyngs in contempt, and he went to jail.

“When they jailed the jailer,” Halliday said, “we can see how determined the court was to ensure that everybody who claimed to act in the king’s name answered to the judges.” From these beginnings, a kind of judicial authority developed that would make it possible to use habeas corpus to protect what we later came to know as civil liberties.

The relationship of the king to his subjects — which included aliens living within the king’s protection — was considered a bond of reciprocity, Halliday explained: “The king protects the subject, and the subject protects the king, literally, with his body.” (The Latin habeas corpus is sometimes translated as “produce the body.”) It was in the king’s best interest to ensure that his jailer, as the king’s authority, acted within the bounds of the law, whenever the body of any subject was detained.

Guantánamo and the Supreme Court

The key in the Supreme Court Guantánamo case (Boumediene v. Bush) was whether noncitizens are entitled to habeas corpus, and if so, whether they must be on American soil to use it. A recent Virginia Law Review article by Halliday and U.Va. Law School’s American legal historian G. Edward White — not yet published when sought out by the Court — was cited four times in the decision and by attorneys on both sides.

Halliday and White identified what the Founding Fathers understood about habeas corpus and why they included the “Suspension Clause” in the Constitution, which reads: “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” Since 1789, the writ has been suspended only a few times, always controversially, including by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 allowing U.S. internment of people of Japanese descent.

The article also showed that the English court consistently allowed foreigners access to habeas corpus. In the 1640s, during the English Civil War, justices used habeas corpus to release those imprisoned by military officers. Between 1689 and 1710, Chief Justice Sir John Holt and his court released hundreds of accused traitors and spies — French, Irish, Scots and English — during wartime and threatened rebellion, while always identifying those who might, by law, rightly merit prosecution.

“Place was not the point in habeas litigation. People were,” Halliday writes.

“Paul’s work sheds light on the original meaning and purpose of the Constitution’s guarantee of habeas corpus,” said Jonathan Hafetz of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, who consulted with Halliday for an amicus brief in the Guantánamo cases. “It shows that efforts to deny habeas corpus to detainees today and to create prisons outside the law contradicts centuries of history and tradition.”

Still, Halliday cautioned, one thing not found in the past is the present, and looking for cases identical to today’s is not the way to use history. Neither is it right to superimpose one generation’s experience on another’s from hundreds of years before, for each lives in a “different mental universe.” Instead, he writes about how he, as a historian, looks at the evidence: “What we find in thousands of cases across thousands of miles are patterns revealing principles about habeas corpus.”

And that’s what it takes, he said. If the past is expected to inform current legal issues, legal and judicial practitioners must do much more serious work in court archives to detect trends and patterns in Anglo-American jurisprudence.

“I want my research to teach American lawyers and judges: Not so fast — don’t be so quick to think that by reading a handful of sources everyone has read over and over again that you can declare, ‘It was thus and such in the past, so we will do thus and such in the present.’ If judges are supposed to be informed by what happened in the past, they need to take much more seriously what it takes to recover that past.”

That kind of historical analysis, he said, “might help us think our way into the problems we confront today from surprising points of entry that we might not otherwise see.”

This approach to research also informs every course he teaches, encouraging his students’ questioning and critical analysis — the heart of the liberal arts education.

Images of writs of habeas corpus are provided courtesy of History professor Paul Halliday, who photographed them for his research purposes. Reproduced by permission from The National Archives, London, England.

The National Archives of the United Kingdom: Making Discoveries Possible

The writs are found at the National Archives of the United Kingdom. Many of the writs had not been viewed since they were tied and wrapped hundreds of years ago. Due to their fragility — imagine how dry and rigid parchment could be after centuries – the National Archives Conservation Department devoted many hours to softening and flattening the writs for Professor Halliday’s use, to his — and our — tremendous gratitude.

A visit to the National Archives Web site will provide this introduction to the revered British institution:

Who we are

The National Archives is a government department and an executive agency of the Secretary of State for Justice. It brings together the Public Record Office, Historical Manuscripts Commission, the Office of Public Sector Information and Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

What we do

The National Archives is at the heart of information policy, setting standards and supporting innovation in information and records management across the U.K., providing advice on opening up and encouraging the re-use of public sector information. Through our efforts in promoting best practice in information management, we look to ensure the survival of today´s information for the future.

The National Archives is also the U.K. government’s official archive, containing 900 years of history with records ranging from parchment and paper scrolls through to digital files and archived websites. The National Archives makes open records available to all, either onsite or online, continuously developing new tools to make history tangible for everyone.

— By Karen Doss Bowman

This story originally appeared in the A&S Magazine.

Media Contact

Article Information

October 7, 2008

/content/uva-historian-rewriting-history-habeas-corpus