Across the University of Virginia, scholars with expertise in the presidency and elections have been closely following the 2020 presidential race, providing insight on how the race might unfold and how factors like the coronavirus pandemic could affect voters.

Ahead of Tuesday’s vote, we checked in with three of them – William Antholis, director and CEO of the Miller Center; Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the UVA Center for Politics; and Jennifer Lawless, Commonwealth Professor of Politics and chair of the Department of Politics.

For more information on the election, see this list of pre- and post-election programs and events at UVA, and monitor the Miller Center “Election 2020 and Its Aftermath” page and the Center for Politics website. The Miller Center will also host several webinars in the days after the election.

Now, here’s what Antholis, Kondik and Lawless will be keeping an eye on.

Timing in Swing States

With polls showing a close race in some swing states between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, Antholis emphasized that all results might not be in on Tuesday night.

“It is quite likely that we won’t know the outcome of the election on Tuesday night, and that is OK,” he said. “That is in accordance with laws in many of these swing states, governing how votes are counted.”

In particular, Lawless said, the high volume of absentee and mail-in voting could delay counts slightly more than usual in some states.

“In prior elections, we have not necessarily needed to wait on that, because we have not had such a high volume of mail-in and absentee voting,” she said.

Scholars at the Miller Center have produced a map showing which states are likely to count votes quickly (“hares”), and which might take longer (“tortoises”), based on election law in those states governing how and when mail-in or absentee ballots are counted. See the full map, and a list of tortoise and hare states, here. It uses electoral projections from Kondik and Center for Politics director Larry Sabato’s team at Sabato’s Crystal Ball.

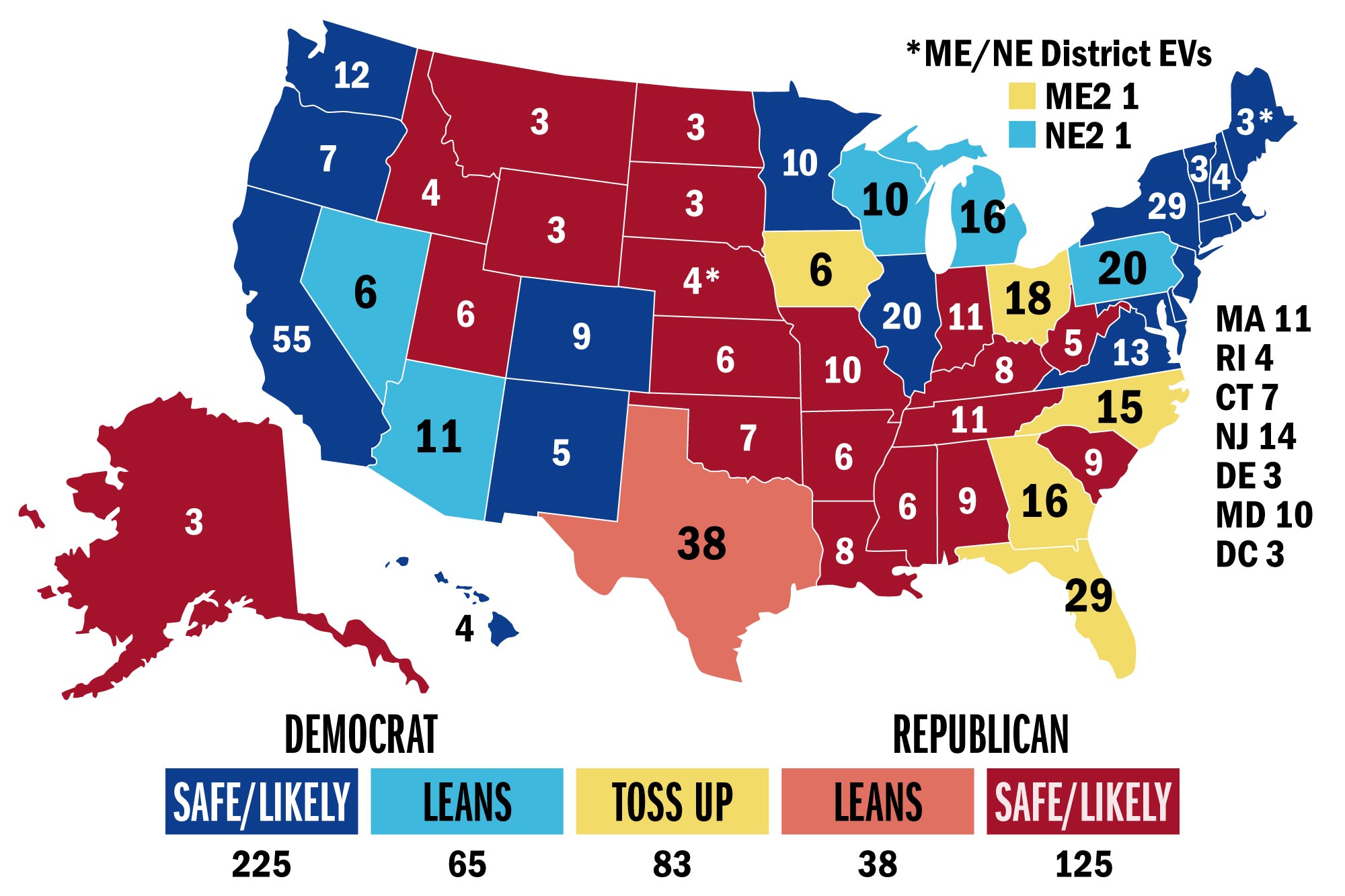

Electoral Votes by State

This map from Sabato’s Crystal Ball shows states that are projected to go for each party, as well as swing states, and the number of Electoral College votes per state. (Image courtesy UVA’s Miller Center)

For example, states like Florida, Georgia and Arizona begin processing absentee and mail-in votes before Election Day. We will likely know the results in those states on Election Night, Antholis said. However, states like Pennsylvania, considered a key swing state, cannot begin to process mail-in ballots until Election Day and will likely need a few days to provide those results. If the race is close enough, that could delay the national election results.

Kondik said he will be paying particularly close attention to results in Florida and Pennsylvania.

“Pennsylvania in many ways is a must-win for Biden, and Florida is a must-win for Trump,” he said. “We will likely know the results in Florida on Election Night, so if I could only watch one state, that would be it.”

Lawless also put Georgia in the mix.

“Both Georgia and Florida should be able to report their counts on Election Night, because state laws allow them to start processing absentee ballots early,” she said. “If Joe Biden wins those states, it’s hard to imagine a scenario by which he doesn’t win the presidency and we would have an announced winner that night. If Donald Trump wins those states, results could come down to votes in other swing states with slower counts, protracting the race.”

Control of the Senate, Lawless noted, is also at stake.

“It is hard to imagine a scenario by which Senate control doesn’t match White House control,” she said.

Historical Precedent

If the election does take longer to resolve, Antholis pointed out that the country has been in that position several times before.

“Historical precedent tells us that results can take a few days to come in, even in ‘normal’ elections where results are fairly clear,” he said. “There have also been five times in American history where there was great uncertainty about presidential election results.”

Dean of Students Allen Groves discussed one of those in last week’s “UVA Weekly” video, reminding students of the 2000 election when George W. Bush defeated Al Gore after a 5-4 Supreme Court decision ended vote recounts in Florida.

The examples Antholis cited include the election of 1800, in which Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr were nominated on the same political ticket, won the same number of electoral votes and the House of Representatives had to break the tie; the election of 1824, when the House chose John Quincy Adams after an inconclusive Electoral College result; the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, which sparked a secession crisis; the 1876 election, when Rutherford Hayes lost the popular vote, but won the Electoral College after contesting results in four states; and the 2000 election.

Looking at general trends of the race, Kondik said he sees some similarities to the 1980 election, when incumbent Jimmy Carter, who, like Trump, was considered an “outsider” candidate when he first won the presidency in 1976, then struggled after a tough year that included economic problems and the Iranian hostage crisis. A Trump victory, Kondik said, could resemble the 1948 election, in which incumbent Harry Truman struggled early in the polls but benefited from a late surge and surprised pundits with a victory over Thomas Dewey.

In many ways, however, Lawless said the chaos of this year feels unique.

“We have never had a presidential election amid a pandemic, with this level of early and absentee voting, as well as a very topsy-turvy economy,” she said.

Growth in Early Voting and Mail-In Voting

Lawless, Antholis and Kondik all pointed to early, mail-in and absentee voting as a key trend in this election that is likely to carry over and grow in future elections.

“There has been an overall trend in American elections toward more people voting early and voting by mail,” Kondik said. “There has been a steady growth in states allowing these options, and in voters taking advantage of those opportunities. I think that trend will continue, and more and more votes will be cast before Election Day.”

Many states that had not already allowed for widespread early voting or vote-by-mail changed their laws this year to accommodate voters’ concerns about the pandemic, Lawless said. Virginia, for example, established Election Day as a holiday and expanded early voting to 45 days before the election.

Increasingly voters have had the option to vote early, or vote by mail. Kyle Kondik expects both options to keep growing. (Photo by Ziniu Chen, University Communications)

“Traditionally, we as a country have not led the world in terms of voter turnout, because Election Day is on a Tuesday and is not a national holiday, and because many states have had restrictions on early or mail-in voting,” she said. “However, the pandemic turned that on its head, and many states modified their laws, registration and early voting processes to make sure that people could vote safely.”

Lawless expects a lower in-person turnout on Election Day, as many people will have already cast their votes, but believes overall turnout will be higher this year than in previous election cycles.

“The pandemic has not only motivated people to cast a vote, but has made it easier for them and prolonged the length of time in which they can vote,” she said. “It’s hard to imagine states turning back on that.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 30, 2020

/content/uva-politics-experts-discuss-three-key-trends-tuesdays-election