Sept. 24, 2007 -- In a world where we all search for something, Ruhi Ramazani searches for understanding.

Officially retired from the University of Virginia in 1994, the professor emeritus of government and foreign affairs has hardly slowed down. He organized an international conference that explored the separation of church and state last spring in Prague and is currently editing a book collecting the papers from that conference. He continues to serve as an outside reader on doctoral committees and to review books in his field.

Now in his sixth decade as a scholar of the Middle East, Ramazani joined the University faculty in 1953. After the publication of two of his earliest books — “The Foreign Policy of Iran, 1500-1941: A Developing Nation in World Affairs” (1966), the first study of Iran’s foreign policy in any language, and its sequel, “Iran’s Foreign Policy, 1941-1975: A Study of Foreign Policy in Modernizing Nations” (1975) — the media dubbed him the “dean of Iranian foreign policy studies in the United States.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, when the standard approach to analyzing international relations was a focus on the great powers, Ramazani stressed the importance of exploring the domestic and foreign policy goals of smaller countries as players themselves, not just as pawns of the larger countries. For much of his career, he has urged American analysts and policymakers to look beyond simplistic interpretations of Iran’s actions to reach a more nuanced understanding of Iranian culture, religion, government, domestic issues and people.

In his work, Ramazani stresses the importance of historical consciousness when interpreting current events. He also emphasizes the complex mix of factors — political, economic, cultural, religious and historical — that combine to influence a government’s actions, both domestically and internationally. As an expert on the Middle East and U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, he has written or edited more than a dozen books and150 articles and book chapters on related topics.

From Teheran to America

Rouhoullah “Ruhi” K. Ramazani was born in Teheran in 1928, the son of Ali Ramazani, a builder-architect, and his second wife, Azam. Ramazani and his two sisters grew up in a prosperous, middle-class Muslim family in Iran’s capital city.

Ramazani’s father liked to take his young son with him to construction sites where he was working. One day, his father took Ramazani to the opening ceremony for a building project that included tennis courts. Iran's leader, Reza Shah Pahlavi (who reigned 1925-41), who had seized power in Iran a few years earlier through a military coup, was touring the project and pointed to a line on the tennis courts saying, “That line is crooked.”

“No, your majesty, it’s not,” his father responded at a time when most people did not contradict the shah. Ramazani’s father directed his workers to demonstrate that the line was straight, which they did and which it was.

Ramazani’s secure, happy life changed dramatically when he was 15; his mother died in his arms of heart disease. His father sought solace in alcohol, and Ramazani assumed responsibility for his two sisters.

Shouldering this family burden without complaint, he continued his studies and earned the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree in literature, then entered The School of Law, Political Science and Economics at the University of Teheran. He took courses in comparative law, civil law and criminal law, and the politics of government, graduating with a “licence” in juridical science in 1952.

While still a law student in need of money, Ramazani took a job as a tutor for a high school dance troupe, which was leaving Teheran for a tour in Turkey. Among the dancers was Nesta Shahrokh, a dark-eyed beauty whose mother traveled with the group as a chaperone. Ramazani and Nesta became friends during the tour.

Back in Teheran after the tour, Nesta and Ramazani’s friendship deepened. In post World War II Iran, the political situation was unstable as communists, nationalists, socialists and Islamists fought for the country’s hearts and minds. Like their elders, university students were politicized. The Communist Party hired people to intimidate students associated with the other groups and the party faithful compiled lists of students to be attacked. One day, as Ramazani sat in class, thugs rushed in and stabbed to death one of his classmates. In the confusion that followed the attack, the other students rushed into the hallways. “Names were called,” Ramazani said. “I heard my name as part of the turmoil. So I called out my own name as I ran through the hallways: ‘Get Ramazani’!”

It was clear to Ramazani that not only did he have no professional future in Iran, but he likely would be killed if he stayed.

“During my law studies, I became infatuated with the U.S. Supreme Court and comparative law,” Ramazani said. He proposed to Nesta, and the couple made plans to emigrate to the United States, where he could pursue graduate studies in law and a life of academic freedom.

The young couple married late in 1951. Early the next year, with savings of $300, they set sail for the United States, passing by the Statue of Liberty on their way to Ellis Island. They both enrolled at the University of Georgia — Ramazani in law and Nesta in home economics.

The newlyweds paid $10 monthly rent for a WWII surplus trailer that had neither shower nor bath. They subsisted on Wonder Bread, bananas and beans that they heated in the can. When their neighbors learned the couple had no cooking utensils, they offered them used pots and pans, which were gratefully accepted.

That first quarter at the University of Georgia, Ramazani took two courses, American government and constitutional law. He worried about the law exam, which would examine his understanding of American case law. “My English was OK, but not up to that,” Ramazani said. “I would sit up from night to morning to decipher the books.” After the exam, Ramazani’s constitutional law professor, Albert Saye, told him that he had received the only A-plus in the course. Because Ramazani wanted to pursue a doctorate in law, which Georgia didn’t offer, his two professors, Saye and Sigmund Cohn, recommended he pursue his interest in international law at the University of Virginia.

“Both of them wrote letters for me,” Ramazani said. “Their letters must have been good. I was not only admitted, but also got a DuPont Fellowship, which paid tuition and fees.”

Joining U.Va. Faculty

In 1953, the Woodrow Wilson Department of Government and Foreign Affairs asked Ramazani to teach a course on the Middle East. He did, teaching nine students in the first course ever offered on the Middle East at U.Va. A year later, Ramazani became the first person to receive a doctorate in the science of jurisprudence in international relations and international law from the U.Va. School of Law.

Hired as full-time faculty after receiving his degree, Ramazani helped build the modern University, said Larry J. Sabato, University Professor and director of the Center for Politics. Ramazani recruited Sabato to the University’s faculty when Ramazani was first chairman of the Department of Government and Foreign Affairs (now the Department of Politics) and Sabato was finishing his doctoral degree at Oxford University. “Ramazani helped build the University into a nationally ranked institution,” Sabato said "There was almost nothing in the international field that he didn’t either run or have a hand in running.”

After living in faculty housing for a few years, Ramazani and his family built a house, which Ramazani designed, in Ivy. Forty-six years later, he and Nesta still live there.

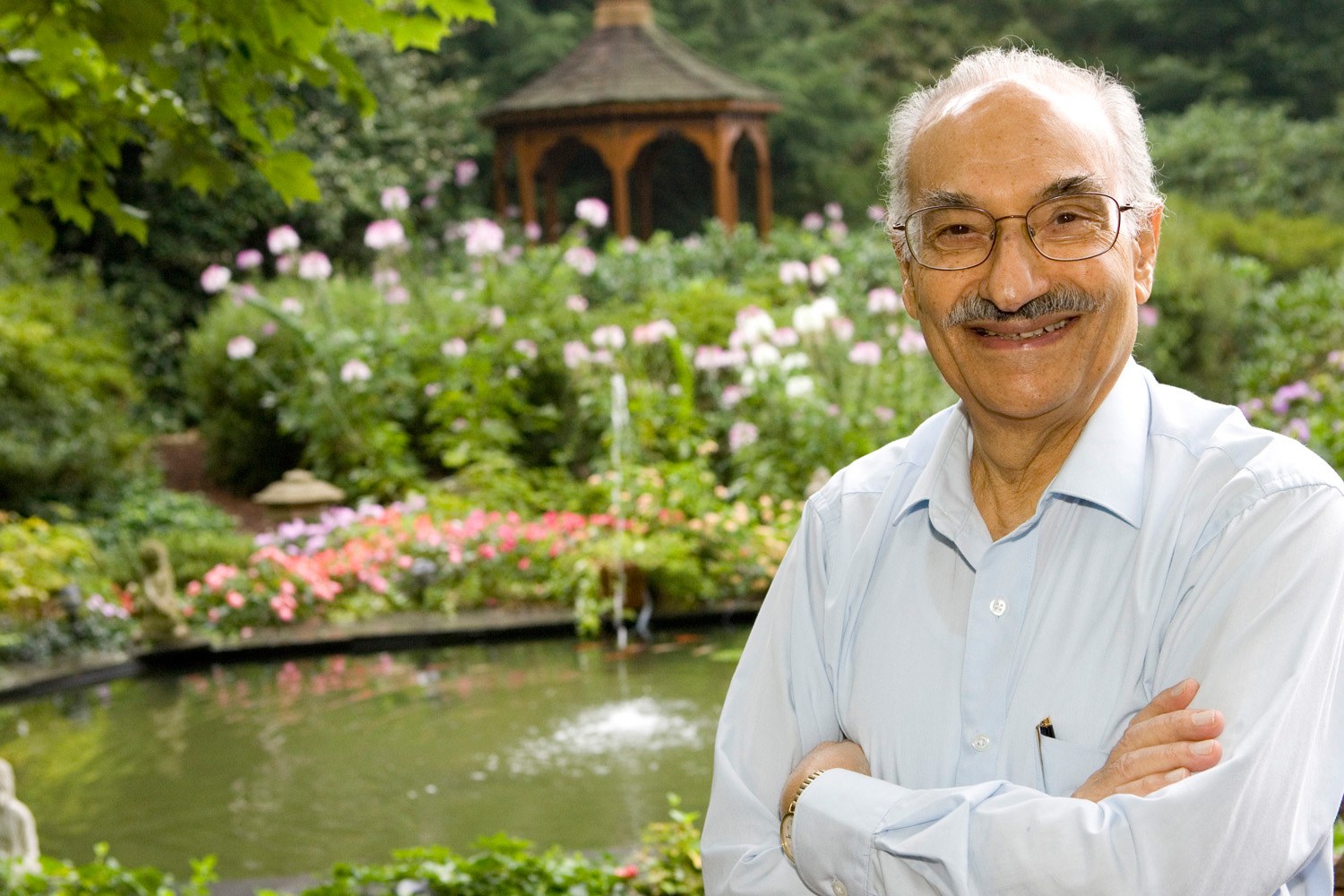

Nestled in the woods near the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Ramazanis’ house has a cozy interior, decorated with Persian artifacts — carpets, metalwork and prints. The dining room opens onto a multilevel deck with a beautiful mountain view. Nesta has planted a stunning flower garden around a lily pond, with fountains and statues set here and there. Not only a talented gardner, she also is known for her Persian cooking.

“I’ve enjoyed many of Nesta’s meals,” said Sabato. “And believe me, if you’re invited to dinner at her house, you go. It’s a culinary extravaganza.”

The Ramazanis have four children and six grandchildren. Their children are: Vaheed, a professor of French literature at Tulane University; David, a furniture maker in Charlottesville; Jahan, the Edgar F. Shannon, Jr. Professor of modern and contemporary poetry, and postcolonial literature, and chairman of the Department of English at U.Va., (who is married to Caroline Rody, associate professor of ethnic American, Caribbean, and women's fiction at U.Va.); and Sima, their only daughter, who worked previously as a social worker but now stays at home with three young daughters.

Ramazani notes with pride that his family holds eight degrees from the University of Virginia.

Gorbachev of the Politics Dept.

Alexander “Sandy” Gilliam, special assistant to the president of U.Va., secretary of the Board of Visitors and a longtime friend of the Ramazanis, finds it difficult to itemize their contributions to the University community over the years because there have been so many. “They’re stalwarts of the University,” he said. “They’re people you can rely on in a crisis.”

Ramazani’s many contributions have been recognized by the University with the creation of a chair in his name, his election to two endowed chairs, a Distinguished Professor Award and a Thomas Jefferson Award. He also has received a Fulbright Award, a Social Science Research Council Award, and awards from the Middle East Institute, the American Association of Middle Eastern Studies, and the Center for Iranian Research and Analysis.

Yet, even with a curriculum vitae brimming with honors and international achievements, Ramazani believes that one of his most important accomplishments has been his teaching. He figures that between his classes in international law and U.S. foreign policy, over 40 years, he’s taught more than 8,000 students.

“I take a lot of pride and joy in my students who have gone on to be successful,” Ramazani said. “A young African-American woman came into my class knowing nothing about the Middle East. Now, Rita Ragsdale is the U.S. ambassador to Djibouti. And Nat Howell, another student, was the U.S. ambassador to Kuwait during the first Persian Gulf War.”

James D. Savage, professor of politics, believes that Ramazani’s influence continues to be felt through the careers of his students, particularly those who have gone into diplomatic service. “He’s had a significant impact on the field of government and diplomacy through his students,” Savage said.

Ramazani also has had an important, if unheralded, impact on his beloved University through quiet, behind-the-scenes efforts and discreet negotiations. In his 40 years on the faculty, Ramazani has served on his share of University committees and task forces and — both when asked and unasked — offered top administrators the benefit of his advice.

"Through his career, Ruhi has been a key figure in faculty leadership,” said Leonard Sandridge, executive vice president and chief operating officer. “He has been a quiet advisor to several presidents. His scholarship and commitment to students are widely known.”

In addition to his intellect and experience, Ramazani’s calm demeanor and gracious style have contributed to the success of his many undertakings.

“I can’t think of a person he’s offended,” Sabato said, "and he’s gotten things done, which is hard to do without offending someone."

During two terms as department chair (1976-82 and 1992-94), Ramazani also has greatly influenced the Department of Politics.

When he first joined the department, morale was low. “The senior faculty had all the power and the junior people were marginalized in the running of the department,” said Robert Fatton, the Julia Allen Cooper Professor of Politics and former department chair, who was a junior faculty member when Ramazani first served as department chair. “The assistant professors and even the associate professors couldn’t vote on department measures. That changed under Ruhi.”

As chair, he enacted many changes — instituting regular faculty meetings, including the votes of junior faculty in department decision-making and creating the post of associate chair to help with the administrative workload.

“He was like the Gorbachev of the department,” Fatton said.

The changes that Ramazani enacted democratized the decision-making process, boosted morale and improved the department’s appeal. “Because of that there has been a huge difference in the long-term success of the department,” Savage said. Ramazani made the department “more collegial and attractive to prospective junior faculty.”

Ramazani also had a sensitivity to aesthetics and a Middle Eastern sense of style that improved his colleagues' day-to-day lives, Savage said. “The hallways were painted a depressing, institutional green; he had them painted white. We had metal doors; he had them replaced with wooden doors.”

Ramazani supported the creation of a faculty lounge to foster a sense of community. He also created “Ruhi’s Corner,” a place in his office where people could come in to chat. And on Friday afternoons, he offered “Ruhi’s Tea,” a chance for anyone in the department, no matter how junior, to come in and sip tea with the chairman.

“That was not done before and it hasn’t been done since,” Savage said. “He was opening the department, not just in a formal sense, but also in informal ways.”

Bridging the Divide

Ramazani and Nesta have made arrangements to leave their property in Ivy to the University when the time comes. In the meantime, Ramazani remains active intellectually, connected with the University and engaged in his field. “I don’t think Ruhi will ever stop thinking, reading and writing,” Fatton said.

“One of Ruhi's great hopes has been that he could personally help bridge the divide between the country of his birth, Iran, and the country where has lived for most of his adult life, the United States,” said William B. Quandt, the Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., Professor of Government and Foreign Affairs and an expert on the Middle East. “It remains to be seen whether Ruhi’s hope for reconciliation between the two countries he knows best will take place, but if and when it does, he will have played an important role behind the scenes.”

Written by Charlotte Crystal

Officially retired from the University of Virginia in 1994, the professor emeritus of government and foreign affairs has hardly slowed down. He organized an international conference that explored the separation of church and state last spring in Prague and is currently editing a book collecting the papers from that conference. He continues to serve as an outside reader on doctoral committees and to review books in his field.

Now in his sixth decade as a scholar of the Middle East, Ramazani joined the University faculty in 1953. After the publication of two of his earliest books — “The Foreign Policy of Iran, 1500-1941: A Developing Nation in World Affairs” (1966), the first study of Iran’s foreign policy in any language, and its sequel, “Iran’s Foreign Policy, 1941-1975: A Study of Foreign Policy in Modernizing Nations” (1975) — the media dubbed him the “dean of Iranian foreign policy studies in the United States.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, when the standard approach to analyzing international relations was a focus on the great powers, Ramazani stressed the importance of exploring the domestic and foreign policy goals of smaller countries as players themselves, not just as pawns of the larger countries. For much of his career, he has urged American analysts and policymakers to look beyond simplistic interpretations of Iran’s actions to reach a more nuanced understanding of Iranian culture, religion, government, domestic issues and people.

In his work, Ramazani stresses the importance of historical consciousness when interpreting current events. He also emphasizes the complex mix of factors — political, economic, cultural, religious and historical — that combine to influence a government’s actions, both domestically and internationally. As an expert on the Middle East and U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, he has written or edited more than a dozen books and150 articles and book chapters on related topics.

From Teheran to America

Rouhoullah “Ruhi” K. Ramazani was born in Teheran in 1928, the son of Ali Ramazani, a builder-architect, and his second wife, Azam. Ramazani and his two sisters grew up in a prosperous, middle-class Muslim family in Iran’s capital city.

Ramazani’s father liked to take his young son with him to construction sites where he was working. One day, his father took Ramazani to the opening ceremony for a building project that included tennis courts. Iran's leader, Reza Shah Pahlavi (who reigned 1925-41), who had seized power in Iran a few years earlier through a military coup, was touring the project and pointed to a line on the tennis courts saying, “That line is crooked.”

“No, your majesty, it’s not,” his father responded at a time when most people did not contradict the shah. Ramazani’s father directed his workers to demonstrate that the line was straight, which they did and which it was.

Ramazani’s secure, happy life changed dramatically when he was 15; his mother died in his arms of heart disease. His father sought solace in alcohol, and Ramazani assumed responsibility for his two sisters.

Shouldering this family burden without complaint, he continued his studies and earned the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree in literature, then entered The School of Law, Political Science and Economics at the University of Teheran. He took courses in comparative law, civil law and criminal law, and the politics of government, graduating with a “licence” in juridical science in 1952.

While still a law student in need of money, Ramazani took a job as a tutor for a high school dance troupe, which was leaving Teheran for a tour in Turkey. Among the dancers was Nesta Shahrokh, a dark-eyed beauty whose mother traveled with the group as a chaperone. Ramazani and Nesta became friends during the tour.

Back in Teheran after the tour, Nesta and Ramazani’s friendship deepened. In post World War II Iran, the political situation was unstable as communists, nationalists, socialists and Islamists fought for the country’s hearts and minds. Like their elders, university students were politicized. The Communist Party hired people to intimidate students associated with the other groups and the party faithful compiled lists of students to be attacked. One day, as Ramazani sat in class, thugs rushed in and stabbed to death one of his classmates. In the confusion that followed the attack, the other students rushed into the hallways. “Names were called,” Ramazani said. “I heard my name as part of the turmoil. So I called out my own name as I ran through the hallways: ‘Get Ramazani’!”

It was clear to Ramazani that not only did he have no professional future in Iran, but he likely would be killed if he stayed.

“During my law studies, I became infatuated with the U.S. Supreme Court and comparative law,” Ramazani said. He proposed to Nesta, and the couple made plans to emigrate to the United States, where he could pursue graduate studies in law and a life of academic freedom.

The young couple married late in 1951. Early the next year, with savings of $300, they set sail for the United States, passing by the Statue of Liberty on their way to Ellis Island. They both enrolled at the University of Georgia — Ramazani in law and Nesta in home economics.

The newlyweds paid $10 monthly rent for a WWII surplus trailer that had neither shower nor bath. They subsisted on Wonder Bread, bananas and beans that they heated in the can. When their neighbors learned the couple had no cooking utensils, they offered them used pots and pans, which were gratefully accepted.

That first quarter at the University of Georgia, Ramazani took two courses, American government and constitutional law. He worried about the law exam, which would examine his understanding of American case law. “My English was OK, but not up to that,” Ramazani said. “I would sit up from night to morning to decipher the books.” After the exam, Ramazani’s constitutional law professor, Albert Saye, told him that he had received the only A-plus in the course. Because Ramazani wanted to pursue a doctorate in law, which Georgia didn’t offer, his two professors, Saye and Sigmund Cohn, recommended he pursue his interest in international law at the University of Virginia.

“Both of them wrote letters for me,” Ramazani said. “Their letters must have been good. I was not only admitted, but also got a DuPont Fellowship, which paid tuition and fees.”

Joining U.Va. Faculty

In 1953, the Woodrow Wilson Department of Government and Foreign Affairs asked Ramazani to teach a course on the Middle East. He did, teaching nine students in the first course ever offered on the Middle East at U.Va. A year later, Ramazani became the first person to receive a doctorate in the science of jurisprudence in international relations and international law from the U.Va. School of Law.

Hired as full-time faculty after receiving his degree, Ramazani helped build the modern University, said Larry J. Sabato, University Professor and director of the Center for Politics. Ramazani recruited Sabato to the University’s faculty when Ramazani was first chairman of the Department of Government and Foreign Affairs (now the Department of Politics) and Sabato was finishing his doctoral degree at Oxford University. “Ramazani helped build the University into a nationally ranked institution,” Sabato said "There was almost nothing in the international field that he didn’t either run or have a hand in running.”

After living in faculty housing for a few years, Ramazani and his family built a house, which Ramazani designed, in Ivy. Forty-six years later, he and Nesta still live there.

Nestled in the woods near the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Ramazanis’ house has a cozy interior, decorated with Persian artifacts — carpets, metalwork and prints. The dining room opens onto a multilevel deck with a beautiful mountain view. Nesta has planted a stunning flower garden around a lily pond, with fountains and statues set here and there. Not only a talented gardner, she also is known for her Persian cooking.

“I’ve enjoyed many of Nesta’s meals,” said Sabato. “And believe me, if you’re invited to dinner at her house, you go. It’s a culinary extravaganza.”

The Ramazanis have four children and six grandchildren. Their children are: Vaheed, a professor of French literature at Tulane University; David, a furniture maker in Charlottesville; Jahan, the Edgar F. Shannon, Jr. Professor of modern and contemporary poetry, and postcolonial literature, and chairman of the Department of English at U.Va., (who is married to Caroline Rody, associate professor of ethnic American, Caribbean, and women's fiction at U.Va.); and Sima, their only daughter, who worked previously as a social worker but now stays at home with three young daughters.

Ramazani notes with pride that his family holds eight degrees from the University of Virginia.

Gorbachev of the Politics Dept.

Alexander “Sandy” Gilliam, special assistant to the president of U.Va., secretary of the Board of Visitors and a longtime friend of the Ramazanis, finds it difficult to itemize their contributions to the University community over the years because there have been so many. “They’re stalwarts of the University,” he said. “They’re people you can rely on in a crisis.”

Ramazani’s many contributions have been recognized by the University with the creation of a chair in his name, his election to two endowed chairs, a Distinguished Professor Award and a Thomas Jefferson Award. He also has received a Fulbright Award, a Social Science Research Council Award, and awards from the Middle East Institute, the American Association of Middle Eastern Studies, and the Center for Iranian Research and Analysis.

Yet, even with a curriculum vitae brimming with honors and international achievements, Ramazani believes that one of his most important accomplishments has been his teaching. He figures that between his classes in international law and U.S. foreign policy, over 40 years, he’s taught more than 8,000 students.

“I take a lot of pride and joy in my students who have gone on to be successful,” Ramazani said. “A young African-American woman came into my class knowing nothing about the Middle East. Now, Rita Ragsdale is the U.S. ambassador to Djibouti. And Nat Howell, another student, was the U.S. ambassador to Kuwait during the first Persian Gulf War.”

James D. Savage, professor of politics, believes that Ramazani’s influence continues to be felt through the careers of his students, particularly those who have gone into diplomatic service. “He’s had a significant impact on the field of government and diplomacy through his students,” Savage said.

Ramazani also has had an important, if unheralded, impact on his beloved University through quiet, behind-the-scenes efforts and discreet negotiations. In his 40 years on the faculty, Ramazani has served on his share of University committees and task forces and — both when asked and unasked — offered top administrators the benefit of his advice.

"Through his career, Ruhi has been a key figure in faculty leadership,” said Leonard Sandridge, executive vice president and chief operating officer. “He has been a quiet advisor to several presidents. His scholarship and commitment to students are widely known.”

In addition to his intellect and experience, Ramazani’s calm demeanor and gracious style have contributed to the success of his many undertakings.

“I can’t think of a person he’s offended,” Sabato said, "and he’s gotten things done, which is hard to do without offending someone."

During two terms as department chair (1976-82 and 1992-94), Ramazani also has greatly influenced the Department of Politics.

When he first joined the department, morale was low. “The senior faculty had all the power and the junior people were marginalized in the running of the department,” said Robert Fatton, the Julia Allen Cooper Professor of Politics and former department chair, who was a junior faculty member when Ramazani first served as department chair. “The assistant professors and even the associate professors couldn’t vote on department measures. That changed under Ruhi.”

As chair, he enacted many changes — instituting regular faculty meetings, including the votes of junior faculty in department decision-making and creating the post of associate chair to help with the administrative workload.

“He was like the Gorbachev of the department,” Fatton said.

The changes that Ramazani enacted democratized the decision-making process, boosted morale and improved the department’s appeal. “Because of that there has been a huge difference in the long-term success of the department,” Savage said. Ramazani made the department “more collegial and attractive to prospective junior faculty.”

Ramazani also had a sensitivity to aesthetics and a Middle Eastern sense of style that improved his colleagues' day-to-day lives, Savage said. “The hallways were painted a depressing, institutional green; he had them painted white. We had metal doors; he had them replaced with wooden doors.”

Ramazani supported the creation of a faculty lounge to foster a sense of community. He also created “Ruhi’s Corner,” a place in his office where people could come in to chat. And on Friday afternoons, he offered “Ruhi’s Tea,” a chance for anyone in the department, no matter how junior, to come in and sip tea with the chairman.

“That was not done before and it hasn’t been done since,” Savage said. “He was opening the department, not just in a formal sense, but also in informal ways.”

Bridging the Divide

Ramazani and Nesta have made arrangements to leave their property in Ivy to the University when the time comes. In the meantime, Ramazani remains active intellectually, connected with the University and engaged in his field. “I don’t think Ruhi will ever stop thinking, reading and writing,” Fatton said.

“One of Ruhi's great hopes has been that he could personally help bridge the divide between the country of his birth, Iran, and the country where has lived for most of his adult life, the United States,” said William B. Quandt, the Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., Professor of Government and Foreign Affairs and an expert on the Middle East. “It remains to be seen whether Ruhi’s hope for reconciliation between the two countries he knows best will take place, but if and when it does, he will have played an important role behind the scenes.”

Written by Charlotte Crystal

Media Contact

Article Information

September 24, 2007

/content/uva-profiles-new-series-spotlights-uva-professor-emeritus-rk-ramazani