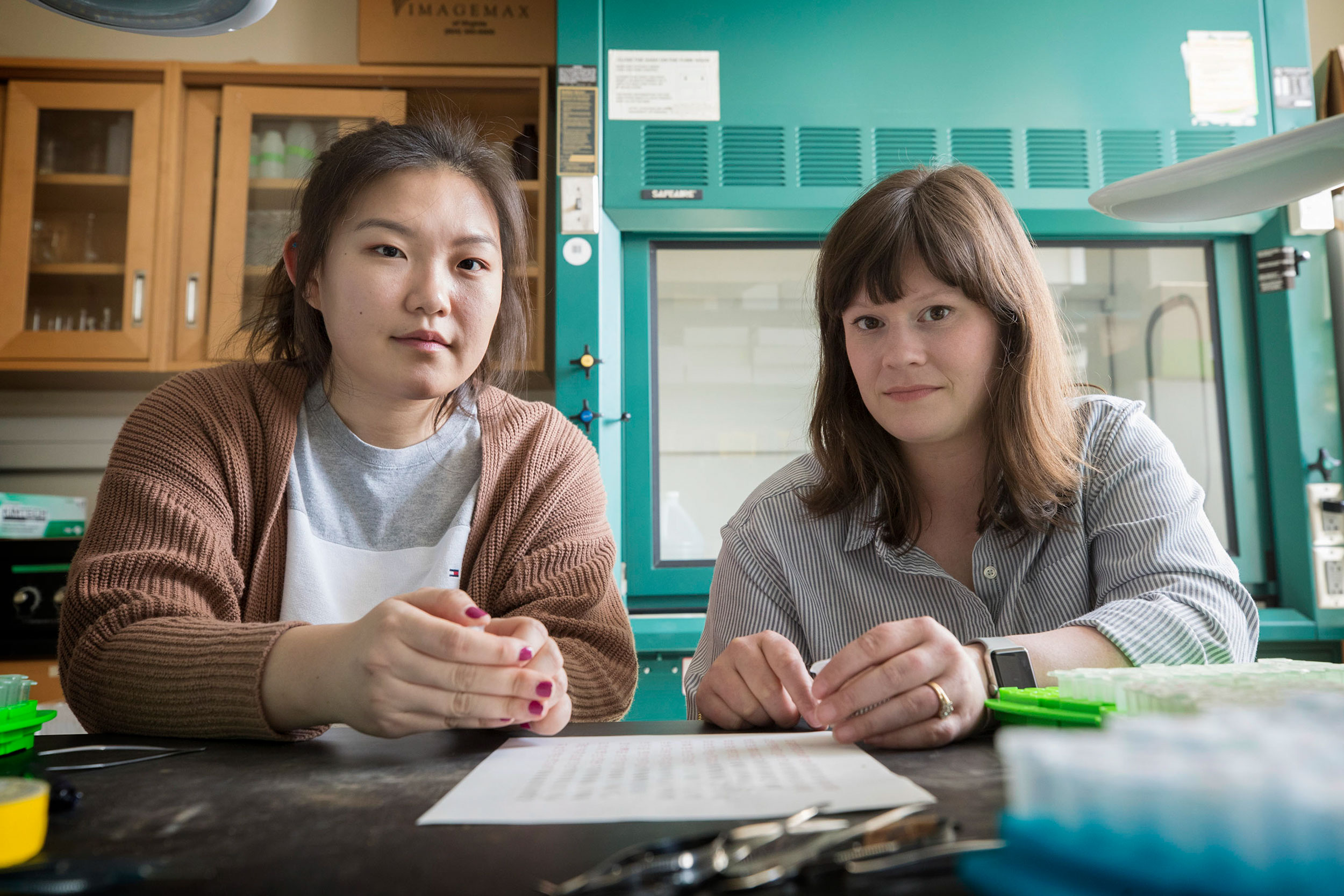

One of Virginia’s best-known spring pollinators, the blue orchard mason bee, has become difficult to find in recent years, and two University of Virginia students are trying to understand why – and how two species of Japanese mason bees might be encroaching on its territories.

Nayoung Lee of Springfield, a third-year biochemistry major and religious studies minor, and Kathryn LeCroy of Pleasant Grove, Alabama, a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in environmental sciences, are studying the distribution of the two species of non-native mason bee species in Virginia in reference to their native range in Asia. Insect species are often limited by climate in their distribution, so the climate of their native area often predicts how far they could spread in a non-native range. This information could indicate how far they can spread through the United States and where they may compete for flowers and nesting resources with native mason bees.

Lee and LeCroy are working together as recipients of a Double ’Hoo research award that pairs an undergraduate student with a grad student mentor.

Nayoung Lee

“The non-natives are already the most common species of mason bee in much of Virginia,” said T’ai Roulston, a research associate professor in UVA’s Department of Environmental Sciences and curator of the State Arboretum of Virginia who is working with Lee and LeCroy. “Mason bees are important pollinators of spring plants, including economically important ones, such as apples and cherries.”

Mason bees are cavity-dwellers, meaning that they nest in existing holes in the environment, such as the hollows of trees, the abandoned nests of wood-boring beetles, or under tree bark. They are called mason bees because once they have laid their eggs, they seal off the nest with mud. They are non-honey-producing, wild pollinators important to agriculture.

“In recent years, concern for the decline in bee populations has increased,” LeCroy said. “With potentially tremendous negative impacts on our ecosystem, the decline in bee population is of legitimate concern, not simply some trendy social media hashtag.”

The information the duo has gathered has proven useful.

“Their research has already shown how abundant the non-native species are, which was completely unknown,” Roulston said. “One of the Japanese mason bees has not been studied at all in North America, and yet it is one of the most dominant spring bee species in the mid-Atlantic region.”

Osmia cornifrons and Osmia taurus are the two exotic species of mason bees from Japan. Osmia cornifrons was imported from Japan as a pollinator, according to LeCroy, while Osmia taurus were not purposefully introduced into the environment.

Kathryn LeCroy

“In the last decade, exotic mason bees have been proliferating throughout the mid-Atlantic while one native mason bee, the blue orchard bee, might be in decline,” LeCroy said. “Based on observations in their native range of Japan, we hypothesized that these two exotic mason bees would exhibit different distributions across Virginia based on winter climate, using a 30-year averaged wintertime temperature, and elevation.”

The researchers engaged more than 100 volunteer “citizen-scientists” in 2017 and 2018, providing them with wooden nesting blocks to place in more than 150 locations in the environment. They used these nesting blocks to capture mason bees.

“After collecting the nests in 2017, we identified the sex and species of each mason bee inside every nest,” LeCroy said, “Our observations from this data set indicate there is a significant difference in exotic mason bee distributions: O. taurus is found nearly everywhere throughout Virginia, but O. cornifrons is only found in areas at higher elevations with lower mean wintertime temperatures.”

LeCroy said this mirrors the patterns of the two bee species’ native ranges in Japan.

“We are unsure at this time as to how far O. taurus could spread beyond Virginia, but projecting its spread in the United States is a crucial next step,” LeCroy said.

LeCroy said that their research has not determined what has caused the decline in native mason bee populations.

”It’s not clear why the native bees are in decline,” LeCroy said. “It could be habitat destruction, predators or pathogens.”

LeCroy enjoys working with the volunteer data collectors and observers. They have a passion for their research and their involvement with the bees, she said, and come from a variety of occupations, from minister or mechanic to librarian.

“We take road trips around the state and listen to the citizen-scientists,” LeCroy said, “I enjoy listening to them and learning from them. It is a two-way street. We share data with each other.”

Lee works with LeCroy in building the nest blocks, collecting data and visiting citizen-scientists.

“Through this project, I have increased my awareness of environmental concerns beyond the decline in mason bee population,” Lee said. “This research gives me the experience of working with other students, faculty members and citizen-scientists. It allows me to ask questions, prepares me for giving talks and enables me to practice working with fine details in a lab setting.”

Lee believes that her work on the mason bee project will be valuable in her future endeavors

“I will use all these experiences in my future career hopefully as a doctor or a researcher,” Lee said. “I absolutely love what I do.”

Lee is the vice president of finance for Phi Delta Epsilon, the pre-medical fraternity. A graduate of West Springfield High School, she plans to pursue a career in medicine, possibly as surgeon.

LeCroy received her bachelors’ degree in biology from Birmingham-Southern College in Birmingham, Alabama, and her masters’ degree in biology (ecology and evolution) from the University of Pittsburgh. She has received a Jefferson Fellowship; a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship; and a Garden Club of Virginia Conservation and Environmental Studies Fellowship. She is a member of the Raven Society and served as the head alumna adviser for a UVA sorority chapter. She said she hopes to work with undergraduate students and citizen-scientists in some capacity in the future.

Roulston said the two researchers make a good team.

“They are very excited about the work they are doing, tireless in planning and carrying out their research and great communicators about their work to audiences,” Roulston said. “They are dogged and inspired people who are fun to travel with, work with in the lab and talk to.”

The students have given public talks about their research, with speaking commitments that extend into the future.

“They are excellent ambassadors for the University and have a great way of connecting the work they do with the general public,” Roulston said.

Media Contact

Article Information

April 15, 2019

/content/uva-research-team-hunts-down-exotic-mason-bees