When University of Virginia sociology professor Jeffrey K. Olick visited the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial a few years ago, he saw something unexpected: a second monument had been erected there. Next to the original that honored Jews who revolted against the Nazis in 1943, the new one commemorated the 1970 visit of German Chancellor Willy Brandt, who spontaneously knelt in a gesture of penitence.

“It is about a memory of a memory,” Olick said. The plaque depicting Brandt kneeling was unveiled Dec. 6, 2000, the 30th anniversary of his famous gesture.

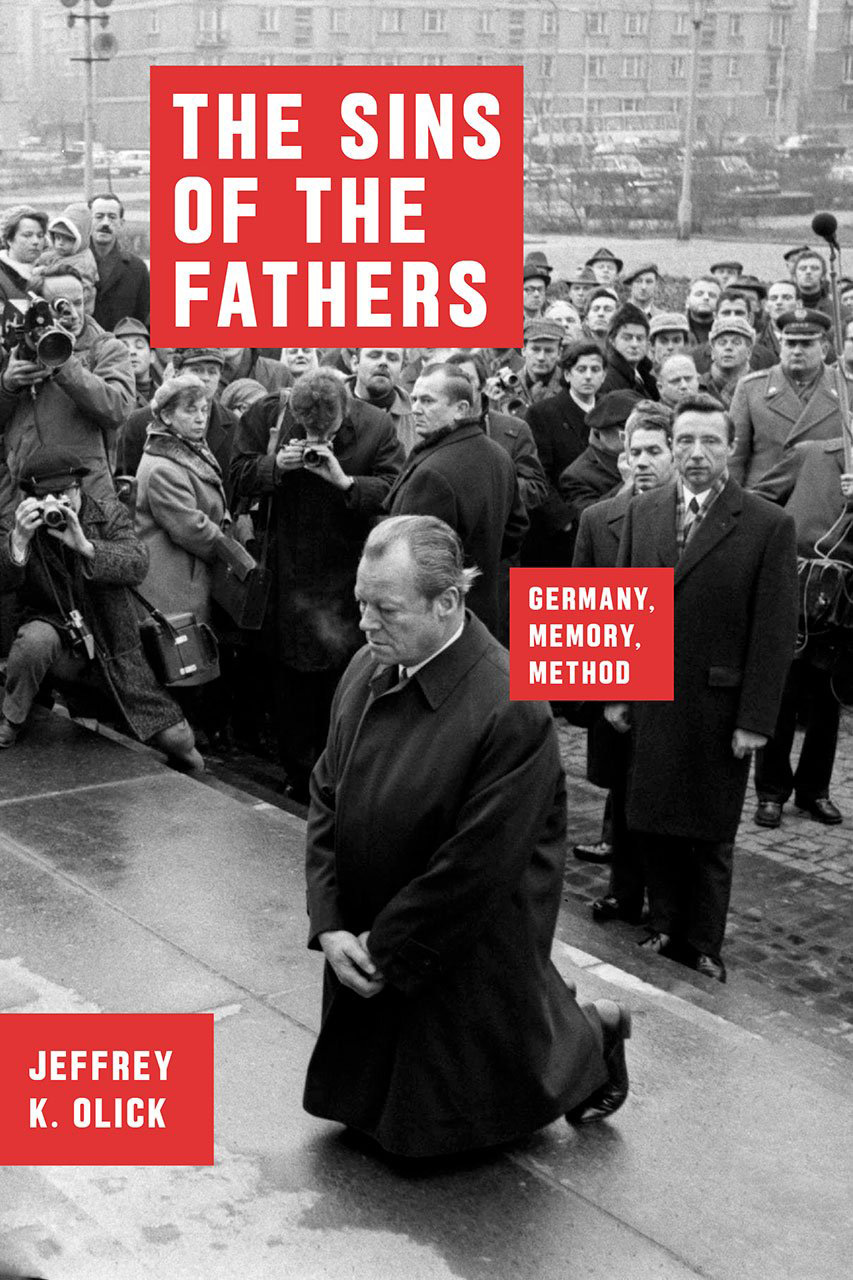

Olick’s new book, “The Sins of the Fathers: Germany, Memory, Method,” published by University of Chicago Press, analyzes how German leaders have addressed the country’s national memory of its Nazi past and the Holocaust since the end of World War II, and the changing approaches they have used, depending on time, place and context.

The book cover photo depicts German Chancellor Willy Brandt spontaneously kneeling at the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial in 1970.

In 1970, critics reacted loudly that Brandt’s move was inappropriate. Polish officials were angry he focused on Jewish war victims. Conservatives were infuriated that he assumed an attitude of contrition. Others supported his sentiment and willingness to show that publicly.

Brandt, who as a young man escaped to Scandinavia during the war, was a symbol to the younger generation and was unburdened with a Nazi past, as some other leaders were, Olick pointed out. (The German chancellor’s political position is akin to a prime minister – the head of government, whereas as the role of president is primarily symbolic as head of state.)

Every leader of Germany, including since unification in 1990, has faced a dilemma about commemoration: “How do you speak for a nation held accountable not only for two devastating wars in one century, but for what many consider to be the worst atrocity in human history?” Olick asks in his book, the culmination of 20 years of research. The book’s purpose is “understanding the work contemporary politicians do to frame the past,” he writes. Whereas his previous books and most others in social history and related disciplines cover shorter, specific periods in German politics after World War II, “Sins of the Fathers” goes from 1949 to the present.

Many – if not all – cultures, nations, communities and other social groups pass down stories that depict their origins, their history, their identity. Every nation faces issues of memory and historical responsibility for something. “There’s not a nation that exists that doesn’t have something difficult in its past,” Olick said.

What happens when the story is repressed, or is fraught with such horrific elements? How does a nation accept historical culpability? Germany is the canary in the mine of historic consciousness, Jeff Olick said. But nations should review how Germany has spoken about its Nazi past before seeing it as a model. Olick, professor of sociology and history who chairs UVA’s Department of Sociology, describes several themes, or “genres,” as he calls them, that German officials have used to talk about the past over the several political periods since the war.

The main goal of German officials’ rhetoric after the war was to deny collective guilt, he said. In the early post-war years, they did not speak directly of the extermination of 6 million Jewish people and others. They spoke of the Nazi regime as an aberration of German nationalism, sought to reassure the world they could correct the problem and it would not be part of Germany’s future. In the interest of rejoining the community of nations, they focused on making changes that showed that Germany could become a “reliable nation,” as Olick calls it.

By the time Brandt became chancellor in 1969, the story changed – to one of seeing Germany as a “moral nation” that accepted full responsibility for the war’s atrocities and displayed collective guilt. The younger generation that had not participated in World War II accepted this story of collective guilt even though they didn’t have any specific involvement to be guilty of. Accepting guilt, the idea goes, makes it then possible to move on, to move past the curse of bearing “the sins of the fathers.”

A later story line called for remembering how Germans suffered during the war, especially in events such as the bombing of Dresden, for example. Germans should not have to go around in hair shirts in perpetuity, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt said in 1975.

Some of the old fears of German power re-emerged during the unification of West and East Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall, but leaders asserted that they could master the past in the latter as they had in the former.

Olick describes the current Germany as telling the story of being a legitimate “normal nation,” like any other, and discusses the rise of the New Right in Germany and xenophobia, which it shares with other European nations.

The aftermath of World War II, including the Nuremburg trials that prosecuted Nazi leaders, gave the world a vocabulary for “crimes against humanity,” for collective guilt and memory, Olick said. Before other nations look to Germany as a successful model, Olick suggests they realize there is no right or wrong way to carry out reparations, to pay the debts of the past. Germany may have done so better than other countries in some ways, but it’s complicated.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 28, 2016

/content/uva-sociologist-explains-how-germans-memories-war-changed-over-time