As inflation continues to surge across the country, Eric Leeper, the Paul Goodloe McIntire Professor in Economics at the University of Virginia, has found a silver lining.

In the classroom, anyway.

“This is an opportunity for teaching,” Leeper said. “When inflation is sitting at 2% all the time, no one is paying attention to it. And when you try to teach about inflation, the reaction is, ‘Why should I care?’ Well, you shouldn’t, until you should.

“And this can happen quickly. Take the (coronavirus) pandemic … How do you think about how markets work in a world like that? How do you price services for a haircut if all the barbers are shut down? These are real-world examples. You want to get people thinking about those things because unprecedented stuff happens all the time.”

“Unprecedented” is one way to describe the current financial climate.

Leeper, who also serves as the director of the Virginia Center for Economic Policy at UVA and is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, spoke with UVA Today about the basics of inflation, why percentages are climbing and what can be done to combat it.

Q. In general terms, what is inflation?

A. You can think about consumers as buying some basket of goods and services. Every month, you buy some amount of food, some amount of clothing, some amount of rent, etc. So the price index that gets looked at basically tracks the prices of all of those things that are in a consumer’s basket of goods and services. When prices on average across that basket go up, it’s called inflation.

Now, prices can change relative to each other. If you look at the price of flat-screen TVs, they have been consistently going down over time, but the prices of medical care have been going up. Those are relative price changes. That’s not inflation. Even though some prices are going down, you can have inflation as long as the prices of the things that people are spending the bulk of their income on are going up.

So you want to think about inflation as an increase in the average price of goods and services in the economy – a steady increase, not just a one-time change.

Q. According to the U.S. Labor Department’s latest report, inflation has risen to its highest rate, 6.2%, since 1990. Why is this happening?

A. I think there are two reasons. One is really about relative price changes, and that is about the issues with supply chains. We’ve got a lot of goods that are sitting in ports. They can’t get unloaded, they can’t get delivered. So there’s a shortage of certain kinds of goods out there. When there’s a shortage of goods, their prices will go up. Now that really is a relative price change, because that’s not saying the price of all goods is going up; it’s just going to be the prices of those goods that are subject to these supply chain problems.

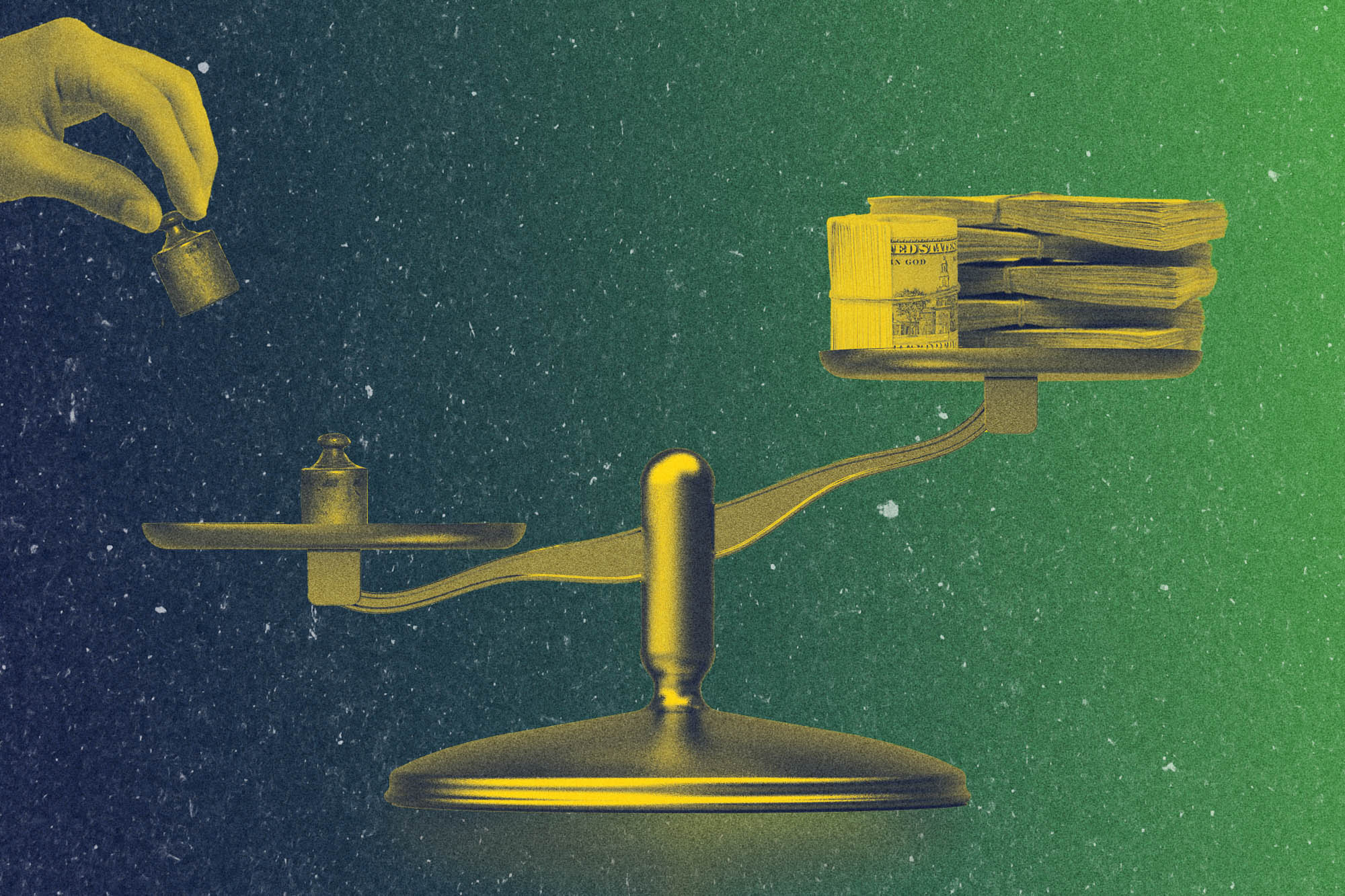

But at the same time, fiscal policy and monetary policy have both been very expansionary over the COVID period. There were six different COVID relief bills that Congress passed, to the tune of about $4 trillion. Some of that was essentially to replace income that workers lost because they couldn’t go to work at all during shutdown. So there was a lot of cash pumped into the economy from those transfers.

Eric Leeper is the Paul Goodloe McIntire Professor in Economics at the University of Virginia. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Then, at the same time, the Federal Reserve has kept short-term interest rates at essentially zero. And it has bought a bunch of Treasury securities and paid for them by creating currency, basically. There’s a lot of liquidity sloshing around in the economy. And so that is the sort of thing that we would generally think of as potentially causing inflation.

Q. What can be done to quell the surge?

A. Markets should be able to take care of that. If there’s a shortage of truck drivers, the way markets would respond to that is by raising the wages of truck drivers to try to encourage more people to take on those jobs. And we’re seeing some of that happen. You would consider that service sector.

A lot of service sector wages have gone up. Amazon is paying its workers more. It’s providing benefits. All of those are increasing compensation and that’s designed to try to encourage workers to re-enter the market.

We’ve also seen workers across the board have reduced their participation rates. They basically have said, “OK, I’m going to live off of savings for a while because it’s just too risky to be out there in the market.” Presumably, when they start to run out of their savings or we get a high enough vaccination rate and things start to look safer, a lot of those workers will return. And that will help to alleviate the supply chain problems.

Q. What practical tips do you have for the everyday consumer during these trying times?

A. There’s only so much you can do. If you’re out looking for a job, you want to try to take into account what people think inflation’s going to be in the next year when you agree to some wage. If inflation is really high, then you’re going to need a higher wage just to keep your purchasing power constant.

But individual workers have only limited influence – although these days, because there is such a shortage of workers in certain workers of the economy, I think workers have more leverage than maybe they’ve typically had in the last couple decades. So they could use that leverage to the extent possible.

Q. Any way to account for inflation in everyday tasks?

A. One way to do that is to postpone when you buy things. I need a new deck, but I’m not getting a new deck put in because lumber prices have been so high. So I’m waiting for lumber prices to come down. Both new and used cars are expensive and scarce these days, so people are going to postpone buying a car. I don’t think you really need to give people tips on that – they’re pretty smart.

People have a lot of common sense. If a gallon of milk has gone up, you may still have to buy that milk. But that means then that you don’t buy the cookies that go with it. People are going to naturally make those kinds of decisions.

Q. Unemployment rates have gone down, but inflation up. Are these developments related?

A. It’s hard to say because there’s still a lot of excess capacity in the economy. I don’t see inflation getting driven up because the economy’s too hot, which is what some people think about. I think there are a lot of special circumstances, like the supply chain stuff. And then don’t forget all the money that the federal government has pumped in.

The COVID spending, it was $4 trillion, total, and there wasn’t any talk about, “Oh, we’re going to have to raise taxes to pay for this.” Whereas when they talked about the infrastructure bill, it was all about, “How are we going to finance this?” That sends different messages to people. I think there is kind of a lot of unusual stuff going on right now. And sometimes it’s hard to learn from history, as it’s been a long time since we’ve had a pandemic, much less any serious federal response to it.

I think there are some trends that are disturbing, like this labor force participation point. And one of the reasons that the unemployment rate comes down is people leave the job market. So you have to keep in mind that the unemployment rate is a ratio. It’s the number of people who are actively looking for jobs, but can’t find them, over the total number of people in the market. And if you are discouraged or are scared and say, “I’m not even going to look for a job,” then you’re not even in that statistic anymore. So that changes both the numerator and the denominator and the unemployment rate goes down. Just looking at things like the unemployment rate can be misleading when you have a lot of shifts in labor market participation.

Let’s keep current inflation in perspective. If in March 2020, I had been told that by December 2021 real economic activity would be rising steadily, but inflation would be a few percentage points above the Fed’s 2% target for a couple years, I would have said, “I’ll take it. That’s a successful recovery from the pandemic.”

Media Contact

Article Information

December 13, 2021

/content/what-inflation-economist-offers-insight-unprecedented-times-continue