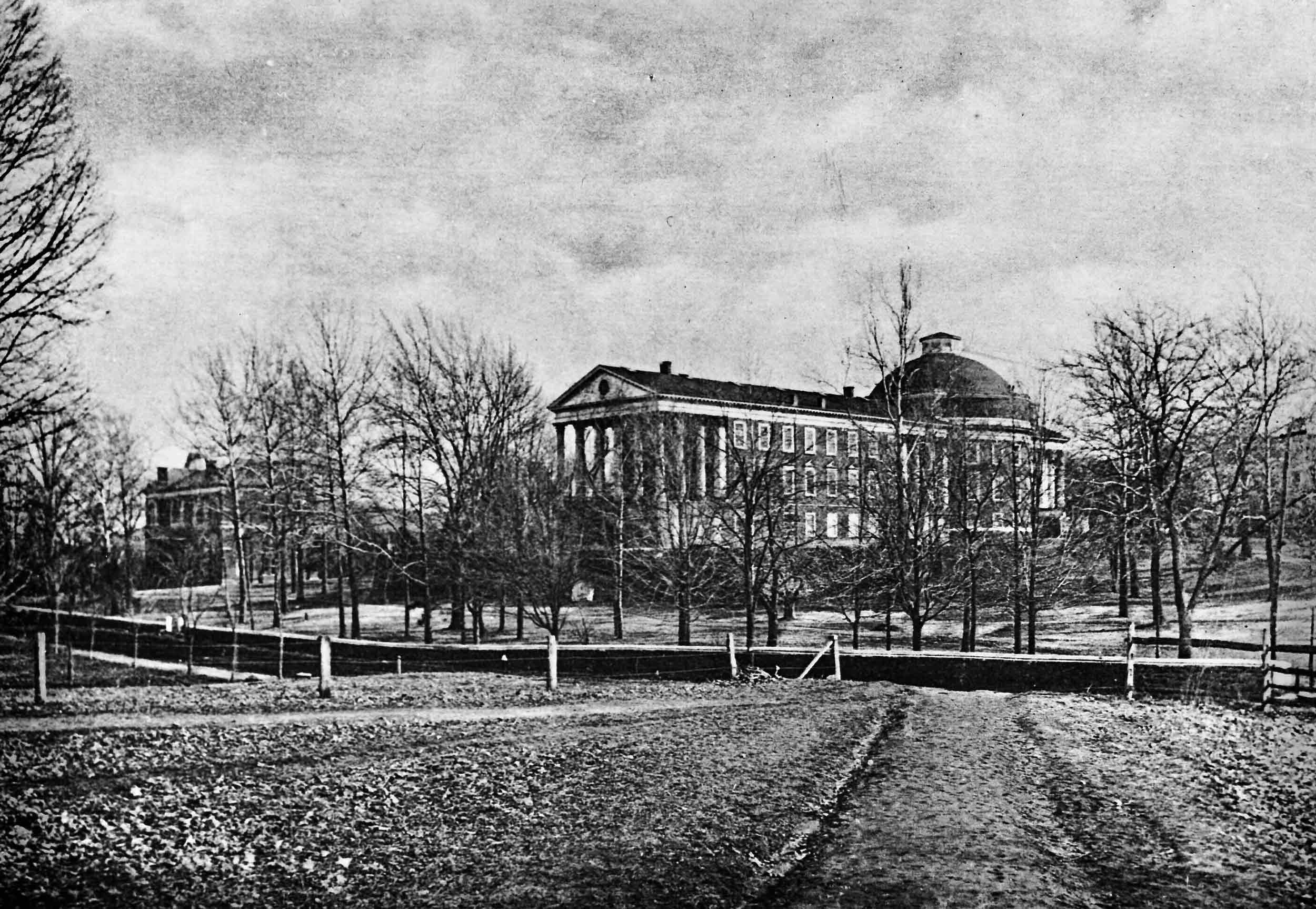

The foundation was started on July 1, 1876, and completed a year later. But Lewis Brooks died the year the building was finished and never got to see it.

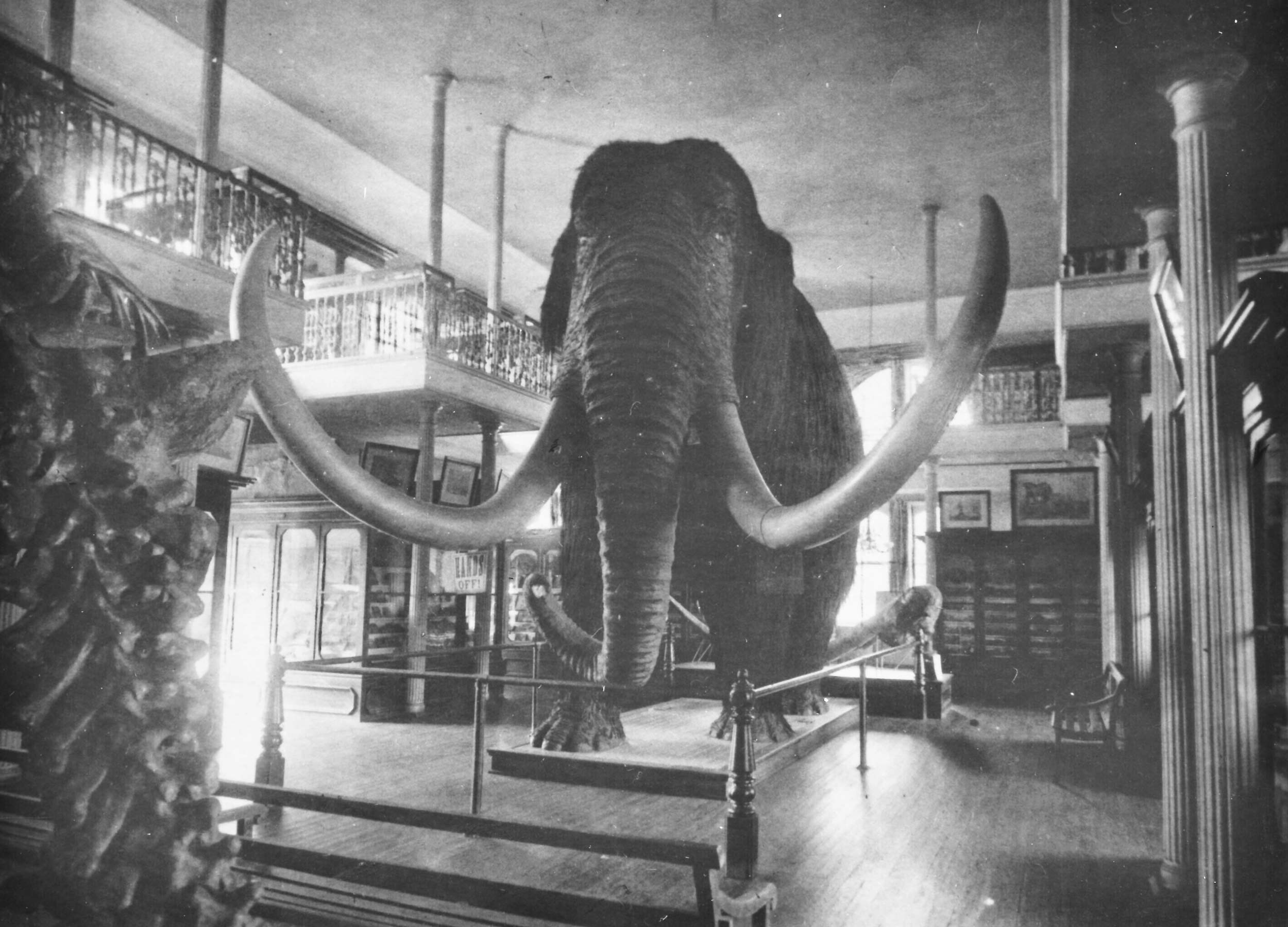

The building is 75 feet tall, built originally with a 25-foot-high, double-story alcove. The museum contained about 25,000 specimens, including a life-sized reconstruction of a mammoth and a “dinosaur skeleton” made of plaster of Paris. Both were later removed.

The Lewis Brooks Museum of Natural Science opened in 1877, an innovative natural history museum for its day, before many other now-more-famous natural history museums.

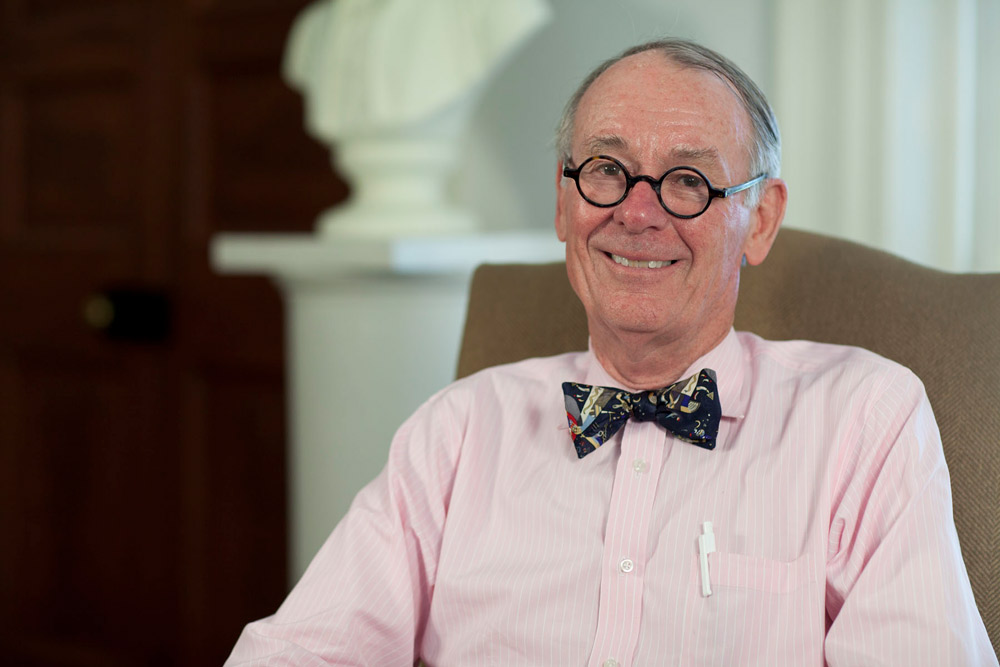

Anthropology professor emeritus Jeffrey Hantman, who had an office in Brooks Hall for 34 years, said disparaging remarks about the building began to circulate in the 1890s. Critics claimed it was too ornate.

Brooks Hall ceased functioning as a museum by the 1940s, and antagonism toward the building peaked in the 1970s. While the Board of Visitors passed a resolution in June 1973 changing the name from Brooks Museum to Brooks Hall, it does not appear that there was ever a BOV resolution to tear down the building.

“I am not aware of a formal move to demolish the building, but discussion of its removal was very much in the air in the late 1970s and early 1980s,” said Brian Hogg, senior historic preservation planner in the Office of the Architect for the University. “It was perceived as not Jeffersonian enough, as not belonging at UVA, as unattractive.”

Some people in the University community tried different tactics to save the building. Mark Reinberger, then an undergraduate student of architectural history, filed an application with the National Register of Historic Places to list Brooks Hall. The building is currently included in the University of Virginia Historical District.

“We were told by someone – I don’t remember who – that Brooks was slated for demolition, and it seemed a reasonable thought because the University was letting Brooks deteriorate as if they didn’t want to keep it,” said Reinberger, now professor emeritus in the College of Environment and Design at the University of Georgia. “We thought perhaps getting it on the National Register would help prevent demolition. At least that is how I remember things happening.”