Until recently, diversity was not a critical priority for highway safety engineers.

To be fair, they were dealing with a more fundamental issue: how to convince stakeholders from government, industry and academia to agree on standardized crash test dummies and computer models, necessary first steps in understanding the biomechanics of accidents and lowering the toll of death and injury on U.S. highways.

They have made substantial progress. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the fatality rate per 100 million vehicle miles traveled decreased 32 percent between 1994 and 2016, the last year statistics are available.

Building Women into the Equation

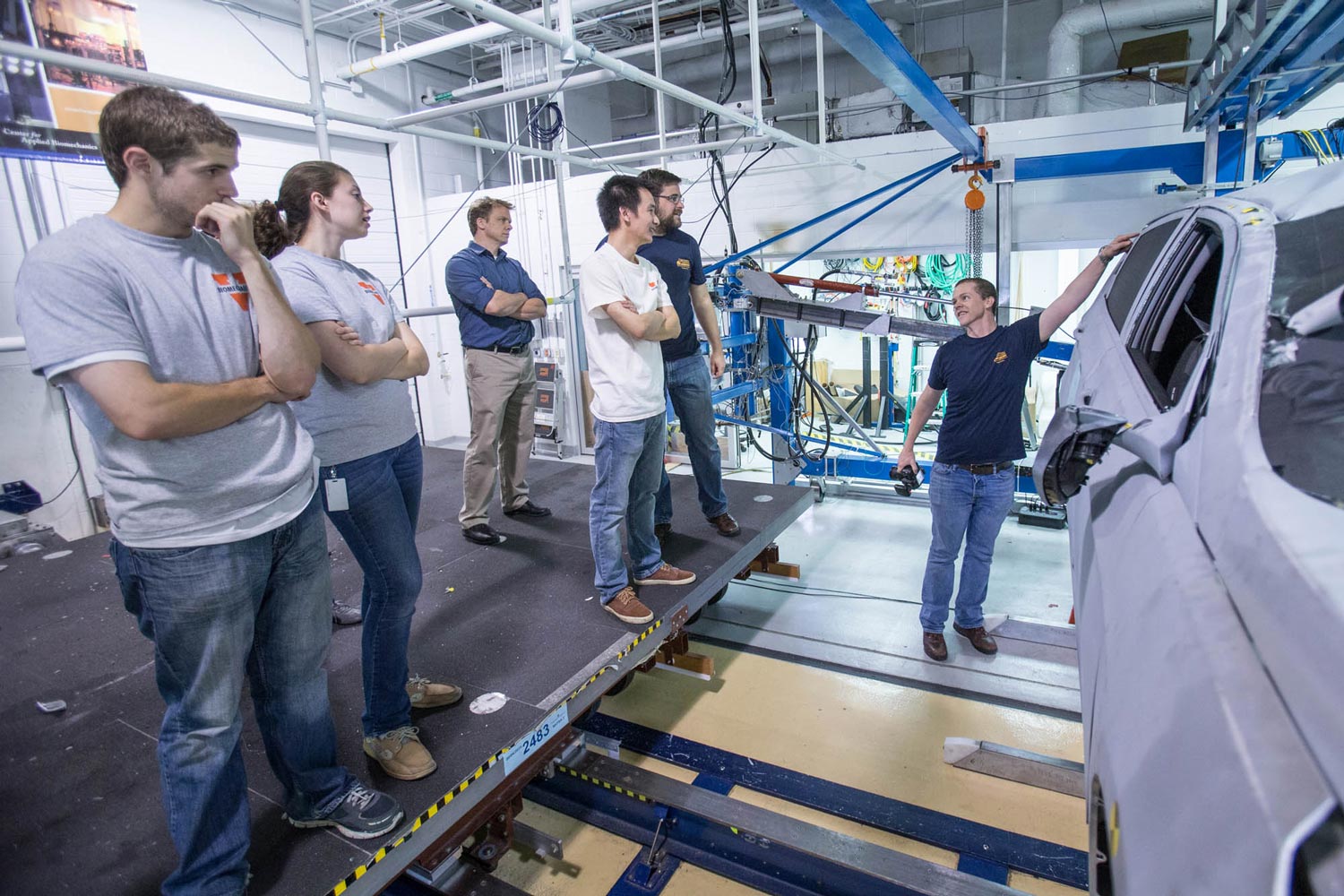

Now researchers are beginning to move beyond the consensus choice – the 50th percentile male – to look at other vulnerable populations, and the University of Virginia’s Center for Applied Biomechanics is taking a leading role. Foremost among these groups are women. In 2011, the center’s researchers published a study demonstrating that women wearing seat belts were 47 percent more likely than male seatbelt-wearers to suffer severe injury, even after controlling for age, height, weight and the severity of the crash. The discrepancy is especially pronounced for lower-extremity injuries.

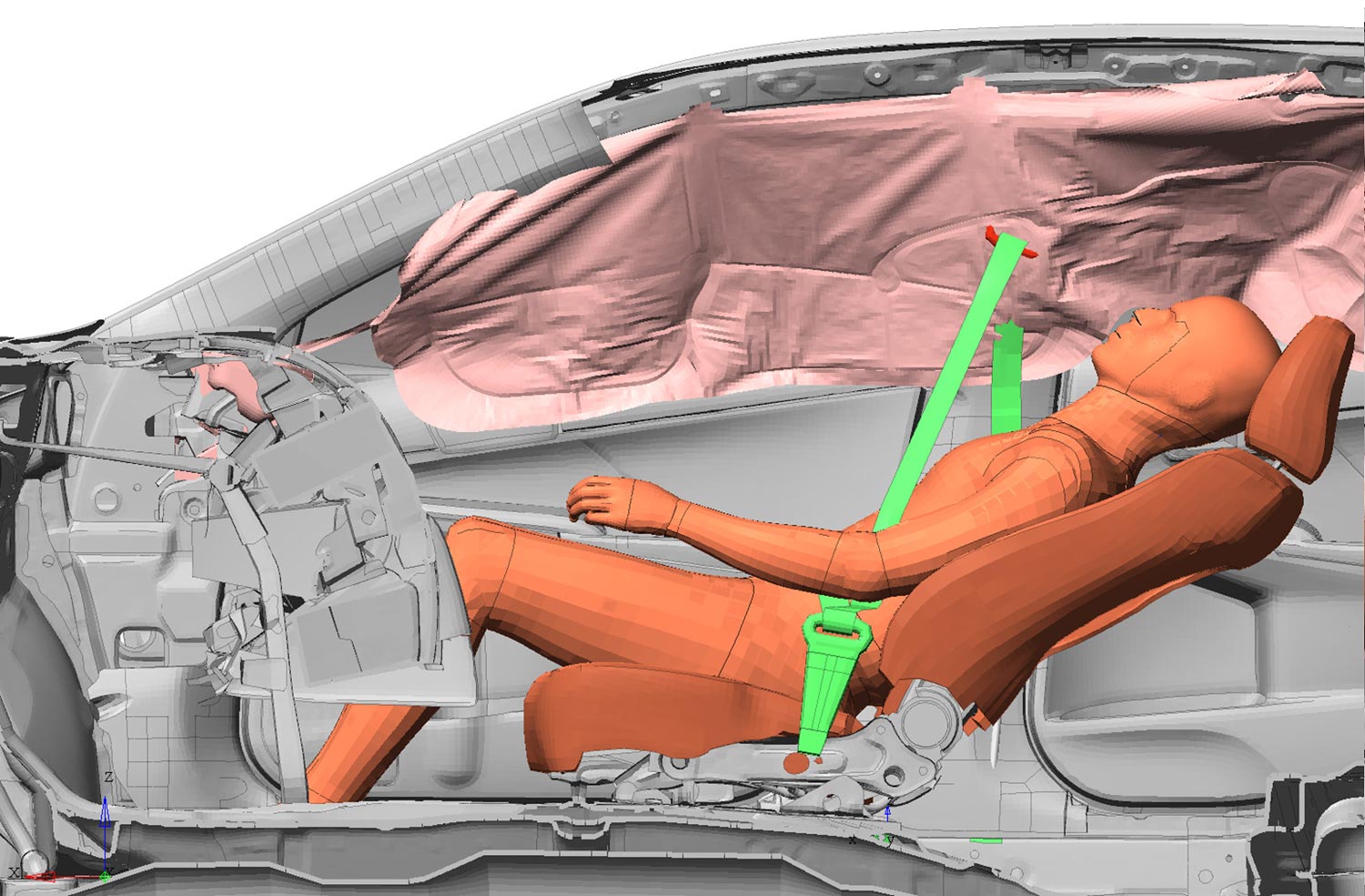

“For years, we used a technique called geometric scaling to forecast how human beings of different sizes would respond to crashes,” said assistant professor Jason Kerrigan, the Center for Applied Biomechanics’ deputy director. “Not only does extrapolation not work for males, but it particularly doesn’t work for females.”

Among the many dissimilarities potentially affecting results are different ligament laxity and bone shape.

One of Kerrigan’s graduate students, Carolyn Roberts, is focusing on this issue. Roberts is trying to understand the biomechanical differences between males and females and determine how these differences affect injury tolerance. With support from Autoliv, one of the largest makers of airbags and seatbelts, she is determining the precise limitations of the current methodologies used to predict female response and developing a companion dataset of female injury response data. This will enable her to identify specific test conditions where male-to-female prediction techniques fail.

She will use her conclusions to develop independent injury models for women as well as to devise ways to extrapolate from male data that are more accurate than geometric scaling. Finally, by comparing male and female models, she will be able to determine which mechanical differences between males and females have the greatest effect on injury.

“Hopefully, with increased understanding of injury tolerance and prediction, automotive manufacturers, auto safety policymakers and injury prevention researchers can work together to make vehicles safer for the entire population,” she said.