August 31, 2011 — The Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues on Monday revealed grim new details from its nine-month investigation of U.S. 1940s-era Public Health Service studies in Guatemala.

From 1946 to 1948, U.S. Public Health Service researchers deliberately infected about 1,300 Guatemalans with syphilis, gonorrhea or chancroid, by inoculation or contact with prostitutes, without the subjects' consent. Fewer than 700 received any form of treatment. This research was first revealed by a Wellesley College historian last October.

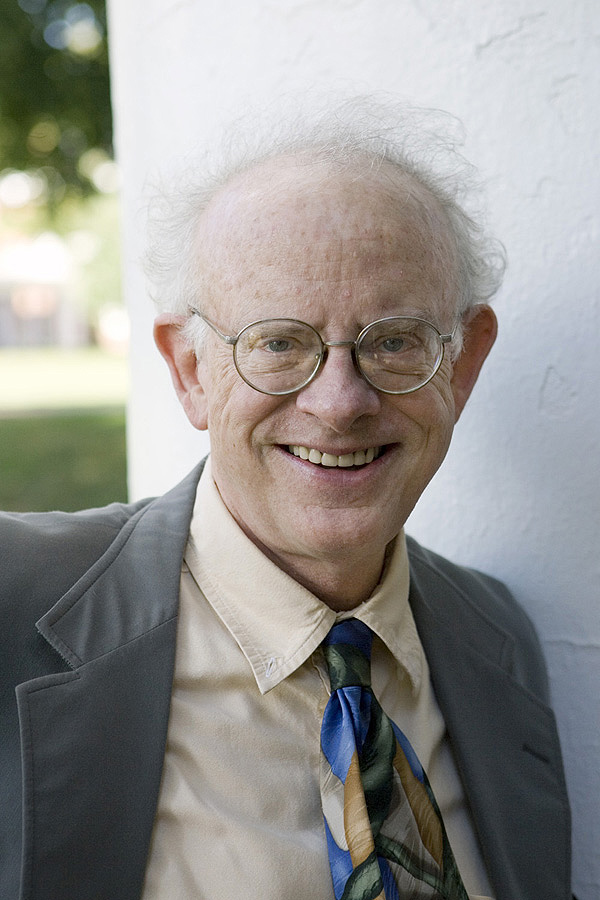

University of Virginia bioethicist John Arras, the Porterfield Professor of Biomedical Ethics and Professor of Philosophy in the College of Arts & Sciences and a member of the presidential commission, helped lead the commission's effort to assess the morality of these experiments in the context of research standards at the time.

"Judging others in retrospect is always a dicey thing," Arras said. "It's always tempting to apply today's more refined and rigorous standards to an earlier time, and we can feel morally superior in doing that."

For instance, the standards of informed consent were much less exacting than they are today, Arras said. In 1947, as a result of the post-World War II Nuremberg trials that exposed horrifying Nazi medical experiments, the Nuremberg Code decreed that patients' informed, voluntary consent is "absolutely essential," especially in non-therapeutic research.

But the U.S. medical profession continued to hotly debate through the 1950s, '60s and '70s the circumstances in which informed consent was absolutely required, Arras said.

The presidential commission's investigation found a compelling context for the experiments: Sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea and syphilis, were rampant among returning World War II veterans and were among the biggest threats to public health at the time. It was estimated that 20 percent of the people living in psychiatric institutions were there because of the neurological effects of advanced syphilis.

The researchers in the Guatemalan study, led by Dr. John Charles Cutler, who was later involved in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments, were looking for a way to prevent the spread of those diseases. But despite that sense of urgency, the studies carried out in Guatemala were poorly designed, poorly executed and entirely unethical, the commission concluded.

The most egregious aspects of the research "amounted to torture, and should be denounced no matter what historical era we're talking about," Arras said. The researchers failed in several respects to uphold the Hippocratic oath's charge to "do no harm."

"It's clear to me that what they did was wrong. They lied to people. They actively deceived," Arras said. In addition to withholding effective treatment from roughly half of those deliberately infected with various venereal diseases, the American researchers did "clearly dangerous things" like performing spinal taps through the back of the skull near the brain stem to check for traces of infection in spinal fluid and, in some cases, to actually produce syphilis in the brain.

Similar venereal disease research conducted in 1943 – led by many of the same researchers who later worked in Guatemala – involved intentionally exposing federal prison inmates in Terre Haute, Ind. to gonorrhea with the promise of immediate treatment. In stark contrast to the procedures followed in Guatemala, Arras said, at Terre Haut the researchers insisted that the prisoners in their study were genuine volunteers who gave informed consent after being fully briefed on all the risks.

The commission concluded from this history that the Guatemala researchers were well aware of the ethical standards that should apply to such research and thus stood morally condemned by their own words and deeds at Terre Haute.

"The attitude toward the Guatemalan people was pretty much what you'd expect if they were doing research on rabbits," Arras said.

At Monday's commission hearing in Washington, Arras recounted the details of a patient named Berta.

Berta was a patient on a psychiatric ward who was injected with syphilis and not given treatment for three months after her initial exposure.

Soon after, Cutler wrote that it appeared Berta was going to die. He did not specify why.

That same day, Cutler put gonorrheal pus from another patient into both of Berta's eyes, her urethra and her rectum, Arras said. Cutler also re-infected her with syphilis. Several days later, her eyes were filled with pus from the gonorrhea and she was bleeding from her urethra.

Soon after, Berta died. She was one of 83 participants who died during the course of the studies. It was not clear whether the participants died as a result of being infected with sexually transmitted diseases.

"I really do believe that a very rigorous judgment of moral blame can be lodged against some of these people," Arras testified Monday. "The most powerful argument is to repeat Berta's story."

From 1946 to 1948, U.S. Public Health Service researchers deliberately infected about 1,300 Guatemalans with syphilis, gonorrhea or chancroid, by inoculation or contact with prostitutes, without the subjects' consent. Fewer than 700 received any form of treatment. This research was first revealed by a Wellesley College historian last October.

University of Virginia bioethicist John Arras, the Porterfield Professor of Biomedical Ethics and Professor of Philosophy in the College of Arts & Sciences and a member of the presidential commission, helped lead the commission's effort to assess the morality of these experiments in the context of research standards at the time.

"Judging others in retrospect is always a dicey thing," Arras said. "It's always tempting to apply today's more refined and rigorous standards to an earlier time, and we can feel morally superior in doing that."

For instance, the standards of informed consent were much less exacting than they are today, Arras said. In 1947, as a result of the post-World War II Nuremberg trials that exposed horrifying Nazi medical experiments, the Nuremberg Code decreed that patients' informed, voluntary consent is "absolutely essential," especially in non-therapeutic research.

But the U.S. medical profession continued to hotly debate through the 1950s, '60s and '70s the circumstances in which informed consent was absolutely required, Arras said.

The presidential commission's investigation found a compelling context for the experiments: Sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea and syphilis, were rampant among returning World War II veterans and were among the biggest threats to public health at the time. It was estimated that 20 percent of the people living in psychiatric institutions were there because of the neurological effects of advanced syphilis.

The researchers in the Guatemalan study, led by Dr. John Charles Cutler, who was later involved in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments, were looking for a way to prevent the spread of those diseases. But despite that sense of urgency, the studies carried out in Guatemala were poorly designed, poorly executed and entirely unethical, the commission concluded.

The most egregious aspects of the research "amounted to torture, and should be denounced no matter what historical era we're talking about," Arras said. The researchers failed in several respects to uphold the Hippocratic oath's charge to "do no harm."

"It's clear to me that what they did was wrong. They lied to people. They actively deceived," Arras said. In addition to withholding effective treatment from roughly half of those deliberately infected with various venereal diseases, the American researchers did "clearly dangerous things" like performing spinal taps through the back of the skull near the brain stem to check for traces of infection in spinal fluid and, in some cases, to actually produce syphilis in the brain.

Similar venereal disease research conducted in 1943 – led by many of the same researchers who later worked in Guatemala – involved intentionally exposing federal prison inmates in Terre Haute, Ind. to gonorrhea with the promise of immediate treatment. In stark contrast to the procedures followed in Guatemala, Arras said, at Terre Haut the researchers insisted that the prisoners in their study were genuine volunteers who gave informed consent after being fully briefed on all the risks.

The commission concluded from this history that the Guatemala researchers were well aware of the ethical standards that should apply to such research and thus stood morally condemned by their own words and deeds at Terre Haute.

"The attitude toward the Guatemalan people was pretty much what you'd expect if they were doing research on rabbits," Arras said.

At Monday's commission hearing in Washington, Arras recounted the details of a patient named Berta.

Berta was a patient on a psychiatric ward who was injected with syphilis and not given treatment for three months after her initial exposure.

Soon after, Cutler wrote that it appeared Berta was going to die. He did not specify why.

That same day, Cutler put gonorrheal pus from another patient into both of Berta's eyes, her urethra and her rectum, Arras said. Cutler also re-infected her with syphilis. Several days later, her eyes were filled with pus from the gonorrhea and she was bleeding from her urethra.

Soon after, Berta died. She was one of 83 participants who died during the course of the studies. It was not clear whether the participants died as a result of being infected with sexually transmitted diseases.

"I really do believe that a very rigorous judgment of moral blame can be lodged against some of these people," Arras testified Monday. "The most powerful argument is to repeat Berta's story."

– by Brevy Cannon

Media Contact

Article Information

August 31, 2011

/content/arras-bioethics-commission-condemn-1940s-guatemalan-syphilis-research-unethical