They were rounded up military style, tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans – the vast majority of them American citizens – who had jobs, homes and families. Herded into buses or trains, they were first taken to assembly centers (usually deserted fairgrounds or large racetracks) where they often remained for months, before being transported again to one of 10 American “relocation camps” at sites scattered from California to Wyoming, Arizona to Idaho.

These World War II camps, deemed a “military necessity to protect the U.S. from espionage and sabotage” in the months following the Dec. 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, offered few comforts. Remote, encased in barbed wire and dotted with guard towers, the tarpaper barracks had community latrines, and mess and sleeping areas that offered little shelter from the cold.

The camps, however, and the makeshift hospitals within, provided a fertile training ground for a generation of Japanese-Americans who got their first taste of nursing while imprisoned over the course of the war.

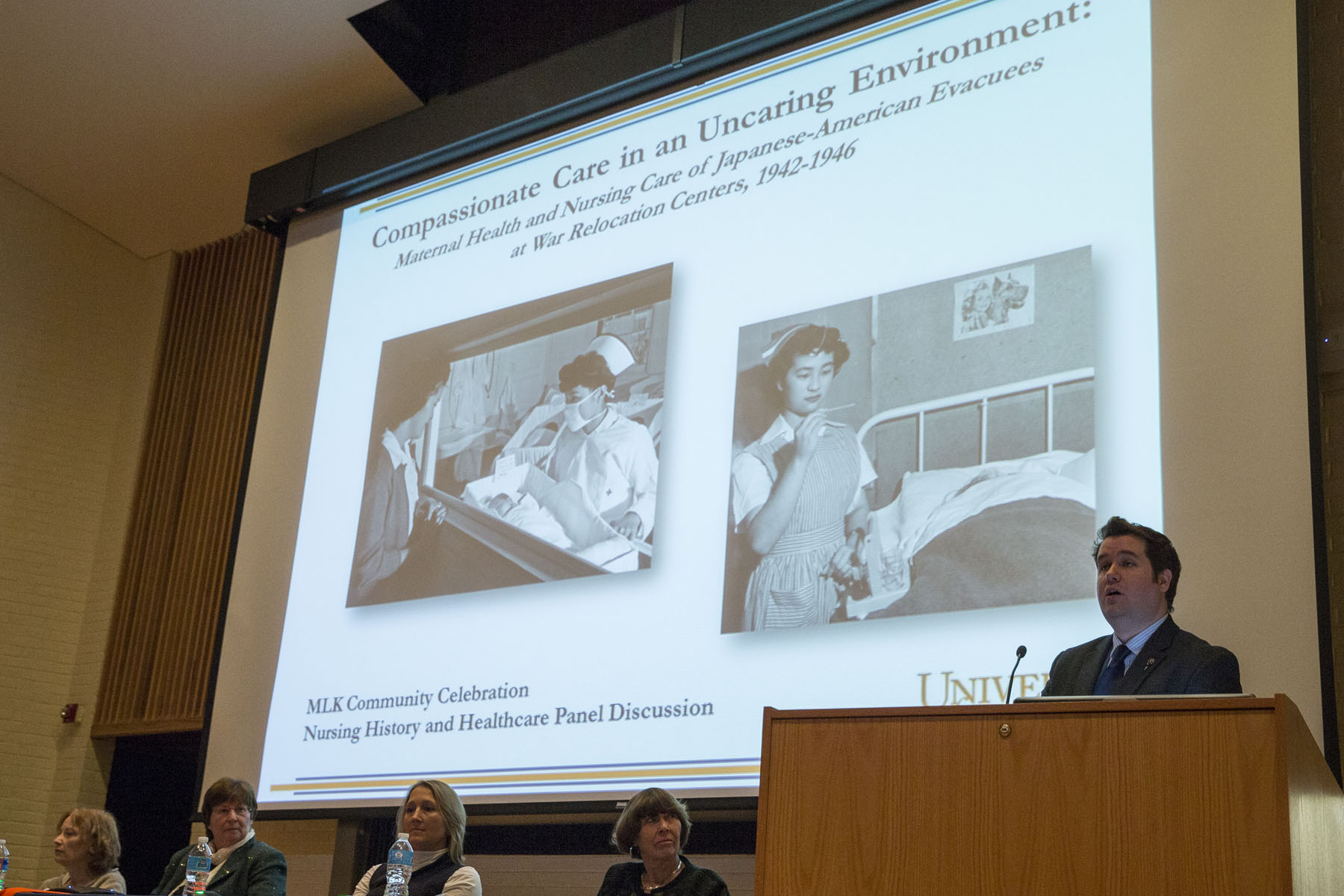

“Until this point, nursing was a white woman’s profession,” said Arlene Keeling, Centennial Distinguished Professor and the director of the University of Virginia’s Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry. The center sponsored the panel discussion, “Compassionate Care in an Uncaring Environment,” held Tuesday at the School of Nursing, as part of U.Va.’s Martin Luther King Day events.

By 1943, however, Congress proposed a nurse cadet training program to accommodate the ever-growing need for nurses.

The Bolton Act, passed unanimously by Congress that June, offered students of nursing funding for tuition and books, and a stipend. Additionally, and perhaps most critically, it also mandated a nondiscrimination policy, enabling American schools of nursing to open their doors to a wide diversity of people. Nursing schools became a route to freedom and a promising career for many young women – including Japanese-Americans living in relocation camps.

“The nursing cadet program turned out to be a silver lining in a very dark cloud,” Keeling said. “It’s particularly difficult for Americans to hear about places like these because it so clashes with our concept of liberty and justice for all.”

Panelist Susan McKay, a nursing professor emerita from the University of Wyoming, described her childhood in California spent just down the road from one such camp, a place she was never aware of until a flurry of Japanese-American students cropped up in her public elementary school after WWII ended.

“By fifth grade, there were seven Japanese students in our class,” McKay recalled, “and it only occurred to me later that they were in the camps while I was playing at home.”

McKay, one of four nurses who addressed an audience in McLeod Auditorium, shared stories of her research on Japanese-American nurses’ trajectories during and after the war. She tracked down and interviewed dozens of young Japanese women, some of them former nursing students plucked from school and interred at camps with their families, including one Wyoming Camp called “Heart Mountain.”

The Heart Mountain Hospital was staffed by Japanese detainees, some of whom were physicians and nurses, and many young women interested in nursing began their training there, McKay said.

The same was true several states away in Arizona, Ph.D. nursing student Rebecca Coffin found, where some chief nurses offered young Japanese-American women specialized routes into the profession and a culture that was “people-minded, not stereotype-minded.”

It was 1988 before the U.S government apologized and offered financial compensation to the Japanese-Americans imprisoned during World War II. By that point – given that the detainees had a twofold greater incidence of heart disease and premature death than average Americans – many had died.

At the hour-long discussion’s close, panelist Pat D’Antonio of the University of Pennsylvania pointed out how tenuous citizenship and human rights can be in times of strife, noting the modern example of racial discrimination experienced by many Muslims and Middle Easterners after Sept. 11, 2001.

“Martin Luther King Day is a time for recognition that all people are equal and have rights – but those rights, even firmly established, can be violated,” D’Antonio said. “We see it over and over when we go to war. So how do we help our students to think about what’s equitable, in spite of our fears?”

Media Contact

Article Information

January 30, 2014

/content/mlk-observance-panel-recalls-how-wwii-internment-camps-advanced-nursing