Although they’re always quiet, the stacks of the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library echo with the whispers of love and lives gone by. They emanate from the pages of thousands of books, where long-dead readers scribbled tiny remembrances and musings in the margins.

A UVA-led project, Book Traces, is cataloging these and other small windows into the past with the goal of creating a massive distributed archive on the history of reading. The project began in Alderman, but has spread to stacks all across the world as a crowd-sourced project to scan and catalog unique marginalia.

It works specifically with pre-copyright books published before 1923, so most of the collection is from the 19th century and includes the writings of book owners during that time period.

Items found inside Alderman’s 19th-century collections vary from lovesick poetry written by the owners, to simple musings on everyday life, to tiny drawing and even cutouts preserved between the pages. UVA English professor Andrew Stauffer, who heads the Book Traces project, said that while it’s rare to find extremely personal notes in the margins, there are some cases where the margins became a diary-like space for their past owners.

“Overall, about 12 percent of Alderman Library books have some kind of writing in them by their original owners. But only a small percentage of those contain emotionally revealing, personal notations,” he said. “Books are semi-private spaces in which to write: they may be picked up, read, loaned or inherited by others, and so people tend toward reticence. But it is clear that readers in previous centuries sometimes reacted to their books by inscribing parts of their lives, including their romantic feelings, within them.”

In light of Valentine’s Day, Stauffer shared examples of some of the love-struck scribblers he and his team have uncovered.

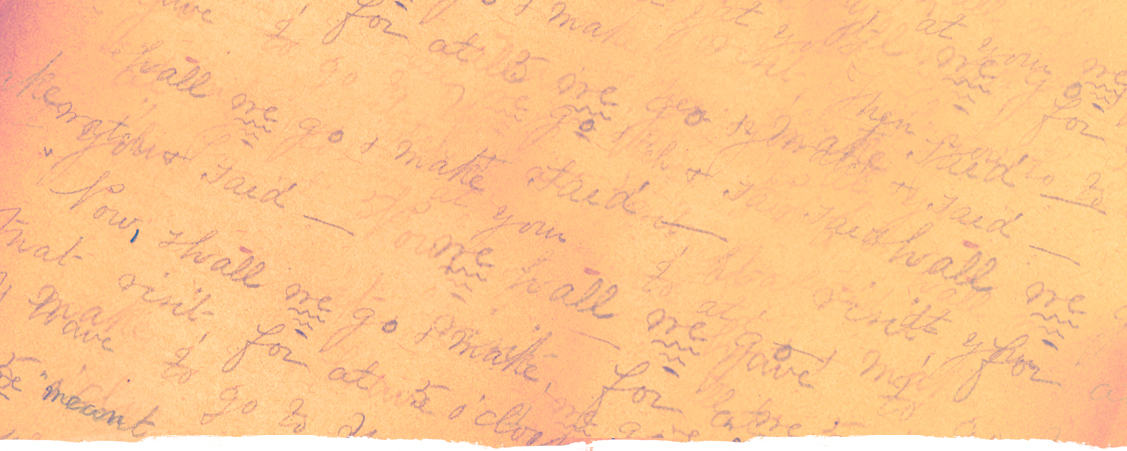

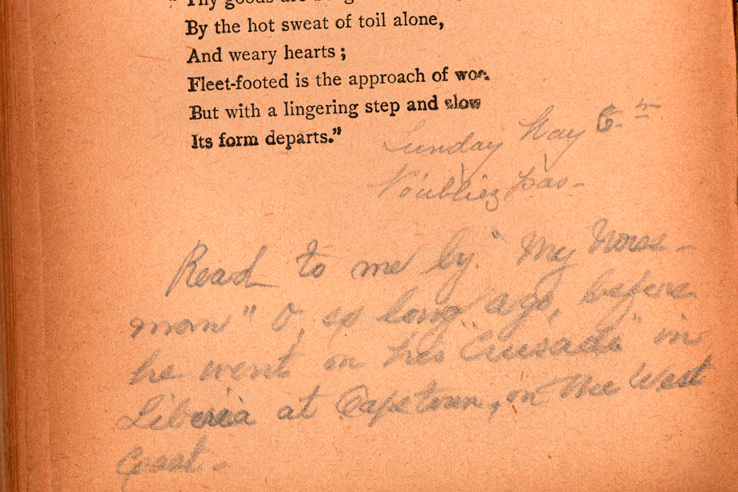

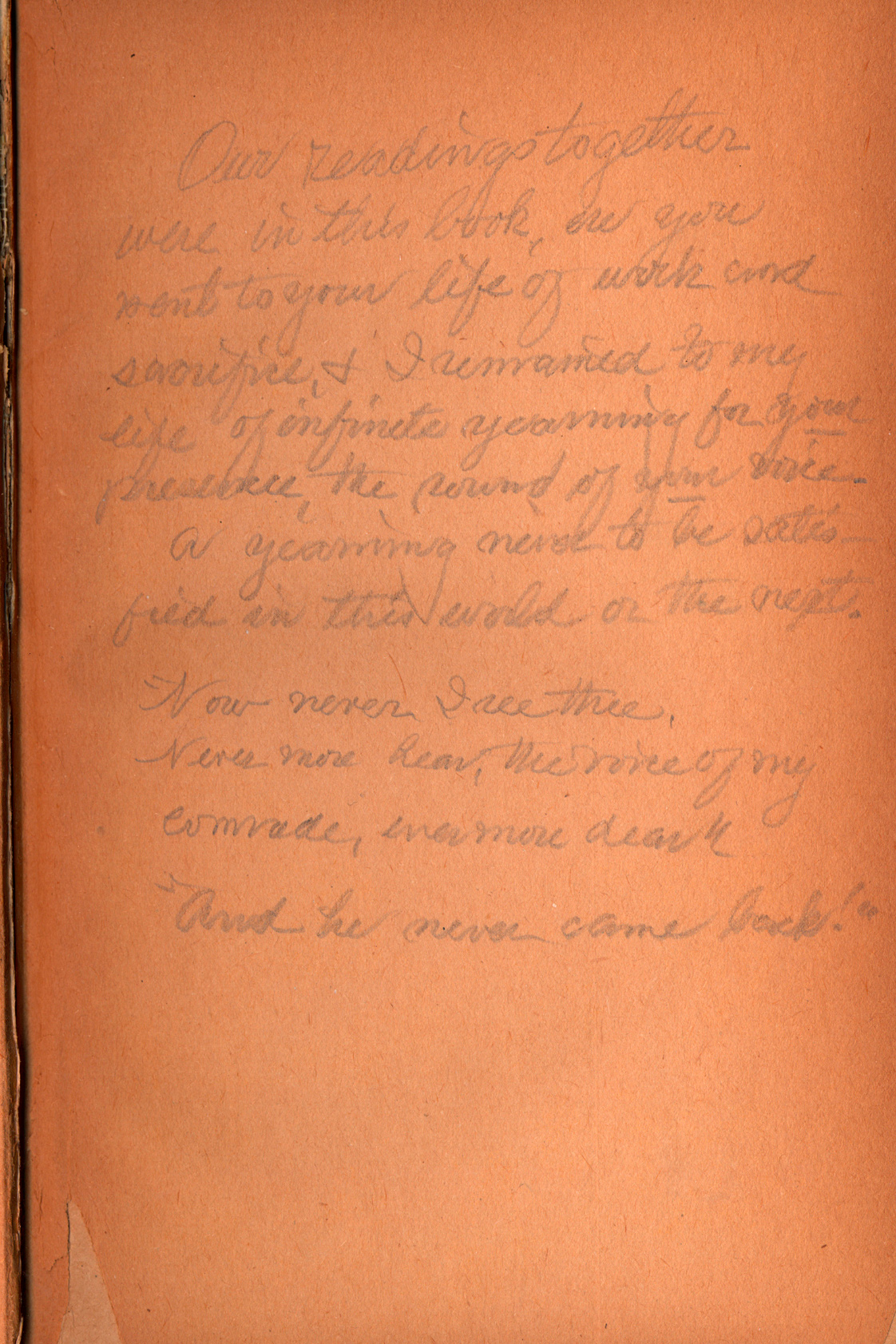

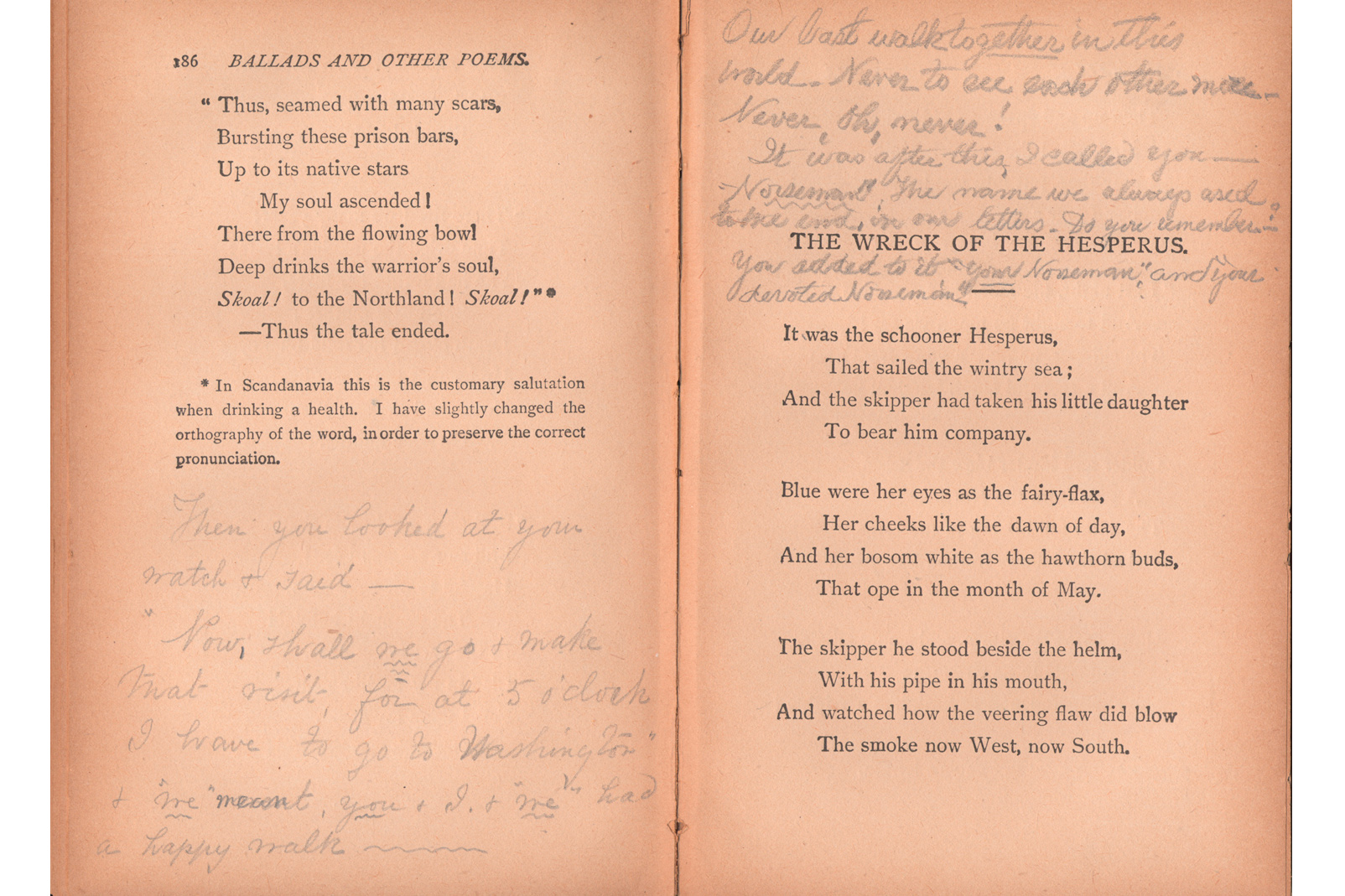

“My favorite has to be the copy of Longfellow’s poetry owned by Jane Chapman Slaughter,” he said. “She uses the book to record her memories of reading aloud with her beloved in the summer of 1900, marking passages with comments like ‘You read this and I said, ‘It just suits your voice,’’ and ‘You read this to me the day you said goodbye.’”

Slaughter was one of the first women to earn her Ph.D. from the University, graduating with a doctorate in Romance languages in 1935 at age 75. Her collected papers and books were later left to the University. The notes in her copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Poems and Ballads” offer a vision into her early life and the longing she felt for a lost love from those days.

Further reading uncovers that her beloved was one John H. Adamson, whose name is inscribed in the book as its original owner. Her notes suggest that Adamson left for Liberia to do mission work in 1900 and never returned to her.

“Sometime later in her life, after she has lost him for good, she annotates her own notes with regretful comments: ‘Our last walk together in this world’; ‘Once, friend of mine, now mine now more!’ and ‘He never came back,’” Stauffer said. “You can see both layers of the relationship on the pages of the book, among the poems.”

The outcome of the lovers communicating across the pages of a copy of James Whitcomb Riley’s “An Old Sweetheart of Mine” is unknown, but their marginalia contains more playful, hopeful gestures of courtship than Slaughter’s sad reflections.

“The narrator [in ‘An Old Sweetheart of Mine’] presents a series of nostalgic memories of a childhood girlfriend, indulged in an upstairs study among ‘old bookshelves’ while his wife and children are out of the way,” Stauffer said. “But the poem ends with an uxorial twist: it turns out that the apparently neglected wife downstairs is the ‘old sweetheart,’ who shows up at the end in her own ‘living presence,’ as domestic bliss subsumes the ‘truant fancies’ of erotic memory.”

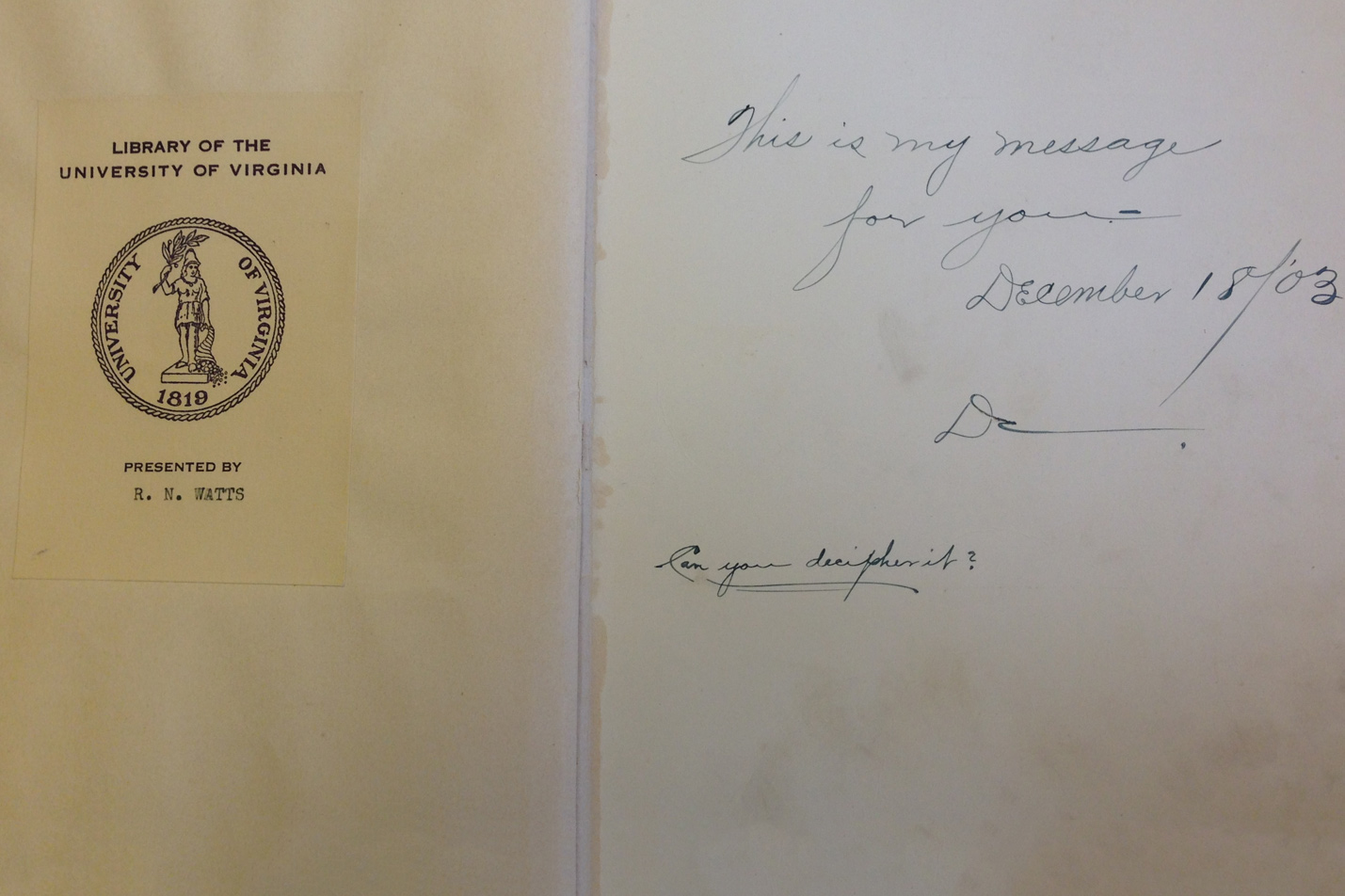

UVA’s copy of the book is coyly inscribed, “This is my message for you. Can you decipher it? December 1903.”

Other notes, like those written in the University’s copy of the narrative poem, “Lucile,” by Owen Meredith, show how readers often turned to authors to help them find the right words and convey them to those they loved.

“Our copy of ‘Lucile’ was given to a woman named Jenny Tayloe in the summer of 1869. Whoever gave it to her used the book and the poem as an attempt to woo her back to him, underlining passages and marking them with dates in their relationship earlier that year, trying to get her to see the poem as about the two of them,” Stauffer said.

All these glimpses of love underscore the importance of the Book Traces project, showing how the written word was integrated into 19th-century life and shaped even the most personal of communications.

“Books are social objects: they pass from hand to hand, often as gifts or shared objects, and so they become good places to communicate feelings in connection with their contents,” Stauffer said.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 13, 2017

/content/uva-library-opens-window-lost-love