Joe McGill did his first sleepover in 2010 at Magnolia Plantation and Gardens in Charleston, South Carolina. He wanted to attract people’s attention to a part of history that was overlooked in that place – and at many others, he would go on to discover.

What was missing: the stories of slaves whose labor made the plantation’s agrarian life and business possible. The humble cabins that provided physical evidence of their lives were often repurposed or falling into disrepair, if they still existed at all.

McGill will visit the University of Virginia this week, where the Slave Dwelling Project that he founded will hold its fourth annual conference Wednesday through Saturday, in conjunction with UVA’s symposium, “Universities, Slavery, Public Memory and the Built Landscape.”

Hosted by the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, the symposium is part of the bicentennial commemoration of UVA’s founding. The events will highlight the recent work of universities and other institutions that have begun to grapple with their histories with slavery, and will consider appropriate preservation and memorialization.

McGill knew slave dwellings and other evidence still existed. As a program officer for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, he advised property owners about how to preserve significant homes and buildings. He became a tour guide at Magnolia when the family who owns it decided to save several small houses where enslaved laborers had lived.

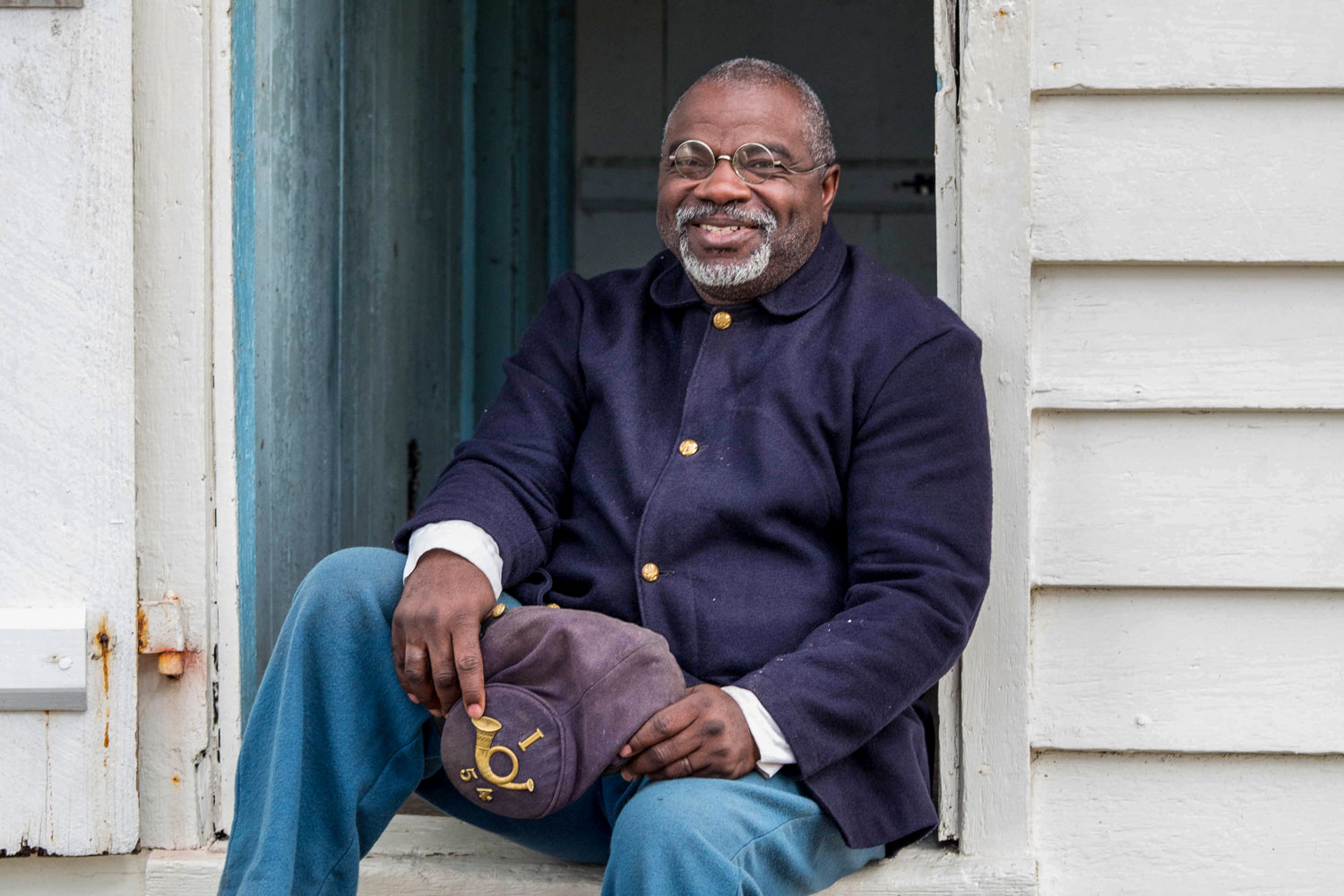

This part of history – the lives of enslaved laborers – hadn’t been talked about very much or was often interpreted incorrectly, said McGill, a descendant of slaves who also plays a black Union soldier of the 54th regiment depicted in the film, “Glory,” in Civil War reenactments.

The mission to get people interested in the importance of these places and the people who lived there moved him to establish the Slave Dwelling Project, and to travel. He found places all over the nation, he said, South and North – yes, there were enslaved people in the North, too. He has stayed – and brought others with him – in some more than 100 sites in 19 states and the District of Columbia where the enslaved once lived. The project serves as a clearinghouse for the identification of the still-existing slave dwellings across the country and resources to document and preserve them. The overnight stays, always conducted with permission, have proved helpful in bringing attention to these places that might be on private properties or public institutions. McGill said he wants to spread “the message that the people who lived in these structures were not a footnote in American history.”

More than 75 people, including symposium speakers and UVA students, have signed up to participate in the Slave Dwelling Project experience Wednesday night, which includes sleeping outside overnight near known sites of slave dwellings at the University.

Gathering at 7:30 p.m. on the Lawn near the statue of Homer, participants will hear music by UVA’s Black Voices and a presentation by the University Guides of the history of the enslaved and free people of color who built and served the University, as well as remarks from McGill. Forming eight-person groups, attendees will sit around candlelit tables to talk about why they’re there. By 10 p.m., those registered for the overnight will head for large tents set up in the garden behind Pavilion IX and McGuffey Cottage, near where enslaved workers lived, to spend the night.

The public is invited to the evening event before the sleepover. The rest of the symposium, however, required pre-registration and is full.

“We need more institutions like UVA that are willing to confront this subject,” McGill said.

A couple of years ago, Dr. Marcus L. Martin and history professor Kirt von Daacke, who co-chair UVA’s Commission on Slavery and the University, and former research associate Kelley Dietz talked about their work at that year’s Slave Dwelling Project conference.

“Now we’re collaborating to bring together an even larger group of people to hear about UVA’s work and put it in the context of work being done by other universities and organizations,” said Prinny Anderson, secretary of the Slave Dwelling Project’s board of directors.

“During the conference, we are holding a panel presentation that we created for UVA, with panelists who are descendants of UVA’s enslaved and free people of color, along with descendants of Highland, Monticello and Montpelier, to talk about what impact it has had for them to be engaged with the place where some of their ancestors were enslaved or at work.” A great-great-great-great granddaughter of Martha and Thomas Jefferson and a five-times-great-niece of Martha’s half-sister, Sally Hemings, Anderson was part of the team that organized the Monticello Community Gathering in 2007, bringing together 250 descendants of people who had lived and worked at Monticello during Jefferson’s time period.

Most of the Slave Dwelling Project’s sleepovers are not quite so elaborate, but the goals of education and action remain the same.

“What we’re trying to do each time is create a setting in which people feel able to talk about slavery, their personal connection to slavery, if any, and the legacies of slavery in current times, be that police violence against men of color, memorials to Confederate generals, or gentrification,” said Anderson, who has been a supporter of the project for about five years.

She said they’d been interested in holding a sleepover involving college students. “Students bring a lot of energy and curiosity to projects, and we were intrigued by the idea of mobilizing more students to be involved with UVA’s work,” she said.

The Slave Dwelling Project will continue, McGill said, to help enlighten, preserve, interpret, maintain and sustain the history and physical objects that show the lives of African-Americans who had to live in slavery.

Media Contact

Article Information

October 17, 2017

/content/participants-sleep-out-near-former-slave-dwellings-uvas-academical-village