Editor’s note: Matt Simpson graduated from the UVA School of Law in 2020 and is now competing with the U.S. goalball team in the Paralympic Games in Tokyo.

Like many kids he grew up with in Atlanta, Matt Simpson loved baseball.

He was obsessed with the Atlanta Braves, who won an unprecedented 14 consecutive division titles from 1991 to 2005. He dreamed of being the next David Justice or Terry Pendleton or John Smoltz.

But Simpson’s dream was shattered before he even got to kindergarten. He was 4 years old when he learned that he had a degenerative retina condition that would eventually leave him blind.

Being so young, Simpson wouldn’t understand what that really meant until he grew older. In retrospect, he believes that was a good thing.

“As a kid, you don’t really think about it. You don’t dwell on it,” said Simpson, now a third-year student in the University of Virginia School of Law. “You kind of get used to the idea of what your life is going to be like.”

For Simpson’s parents, Hal and Linda, it was a different story.

When, at the age of 1, Matt began moving his eyes unusually, doctors had said it was something he would grow out of it. When he started sitting extremely close to the television as a toddler, the Simpsons suspected he might have poor vision.

They never imagined that he would someday be blind.

“You think you have a child that has no health issues, and then one day you wake up and somebody tells you that not only does he have a health issue, but that he’s going to go totally blind,” said Hal Simpson, recalling the day of the diagnosis. “It’s very sobering. It catches you off guard because you just weren’t expecting it.”

One of the hardest things to accept was that Matt wouldn’t be able to play baseball.

“From his earliest ages that he could talk, he would say he wanted to be a baseball player,” Hal Simpson said. “He loved baseball.”

Simpson had a tough go of it in elementary school. As a first-grader, he needed a magnifying glass to read. In second grade, he began learning braille.

Meanwhile, he turned his attention to sports like swimming and running, which didn’t rely on vision as much. But something was missing; he didn’t get the same thrill as he did from baseball.

When he was 10, Simpson discovered a new sport.

At a summer camp, he tried goalball, a sport designed specifically for athletes with vision impairment.

Using ear-hand coordination, goalball players compete in teams of three to throw a ball with bells embedded in it into the opponent’s goal. Players determine their locations using tactile markings on the court. Eyeshades allow partially sighted players to compete on equal footing with blind players.

Simpson was hooked. “I loved the idea that goalball was a sport for people who were blind and that once that blindfold was on and the whistle blew, it was all about you and your abilities matched up with those of your opponent,” he said.

Upon his return from the camp, while sitting at the family dinner table, Simpson made a declaration. “He said, ‘Dad, I’m going to play goalball in the Paralympics one day,’” Hal Simpson recalled.

There was just one problem: There wasn’t a place near the family’s home in Atlanta where Matt could regularly play goalball.

So, through the Georgia Blind Sports Association, Hal Simpson started a goalball program.

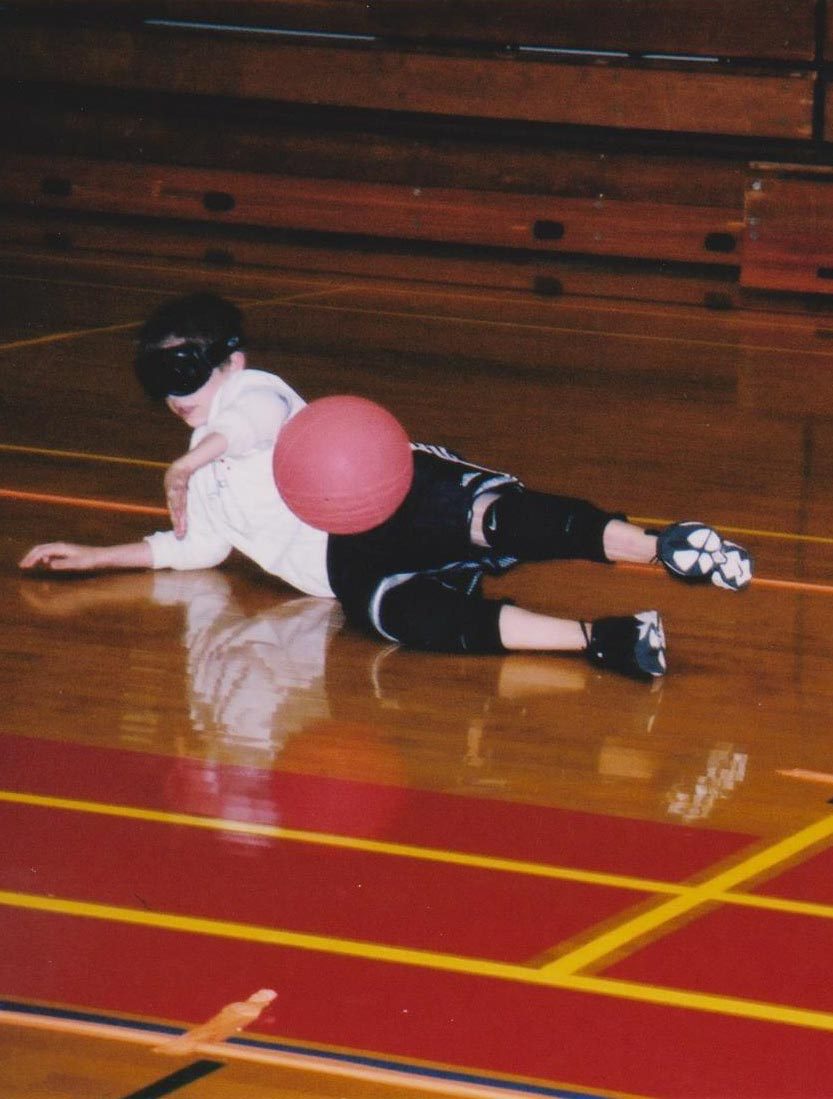

Simpson took up goalball when he was 10 years old. (Photo by Hal Simpson)

Over the next few years, Matt focused on goalball.

When he got to high school, he also tried wrestling. He was on the team all four years, though he didn’t compete in matches until his senior year because he didn’t weigh enough.

That made his connection with goalball all the more special.

“I got to scratch that competitive urge,” said Simpson, who had started using a cane and guide dog toward the end of high school.

Always an excellent student, Simpson elected to attend Washington and Lee University. Throughout his time there, he trained hard – adding 50 pounds to his 5-foot-10 frame – in the hope of making the U.S. national goalball team.

In 2011, he did just that.

Three years later, he won bronze at the world championships. In 2016, he took home silver at the Paralympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

“Sitting there and watching him walk in with the team was a thrill in itself,” Hal Simpson said, “and then a week later seeing him climb up the medal stand and receive a medal. … It was a proud moment.”

Matt Simpson – who had worked as the membership and outreach coordinator for the United States Association of Blind Athletes in Colorado after graduating from W&L in 2012 – later was honored with other Paralympic athletes at the White House.

When he decided to attend UVA Law School, he thought his competitive goalball days might be done. However, he decided to give it one more shot.

After going through tryouts, he earned a roster spot and will be on the U.S. team that will compete in the Parapan American Games beginning Sunday in Peru, seeking to qualify for the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games.

U.S. interim head coach Keith Young is glad Simpson is back in the fold. “When I was asked to help put together the team, Matt was one of the main guys I wanted on the team,” he said. “He can play all three positions and it doesn’t matter to him whether he plays three minutes of a game or a whole game. He’s completely focused on how the team performs. He’s a total team player.

“Matt’s one of those guys you love as a coach because you don’t have to tell him anything. And when you do, he gets it the first time.”

Young said Simpson’s uncanny court awareness separates him from other players.

“He’s super-athletic and he can mentally map the court,” he said. “He does things naturally on the court without missing a beat.

“He’s one of those guys who excels at everything he attempts to do. … It’s pretty exceptional.”

Off the court, Simpson has thoroughly enjoyed his time at UVA.

“It’s one of the best schools in the country for a reason,” said Simpson, who has some light perception, but is now almost completely blind. “Everyone is really supportive. Everyone is really nice and smart, and the professors are wonderful. I couldn’t have asked for a better experience.”

Ditto for his guide dog, a yellow lab named Lacrosse.

“He’s the most popular guy on Grounds,” said Simpson, with a laugh. “He won the ‘Paw Review’ this year, which is a very big deal in law school.”

To do his schoolwork, Simpson uses text-to-speech software that reads everything aloud for him.

“In some ways, I’m at an advantage,” Simpson said, “because I can just tell my computer to read it all to me and my eyes don’t get tired. I can sit there and listen all day. I can crank the speed way up and get through the massive piles of reading.”

Simpson said one of his favorite professors has been John Jeffries, David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law. “He was one of those professors you take and just never forget,” he said. “But everyone at the Law School has just been amazing. You get there and you realize that you’re among some of the smartest people at what they do in the whole world. That’s been a pretty amazing thing – to be class with those types of people every day.”

Simpson – whose older sister played soccer at the University of Maryland – has found time in his schedule to introduce goalball to the UVA community. With the help of Martin Block, a professor in UVA’s Curry School of Education and Human Development’s kinesiology department, Simpson led a clinic for 15 students in April.

“After being blindfolded,” Block said, “I am even more impressed in how people who are blind navigate their environment.”

Block said the clinic was a great success, and Intramural-Recreational Sports is interested in hosting another, and perhaps sponsoring a tournament this spring.

Block said a handful of universities have started intramural goalball programs. An undergraduate student – whose mother works at the Maryland School for the Blind – is trying to start a club at UVA.

“Goalball is a great game,” Block said. “It is fast-paced, and there is skill involved with rolling and blocking the ball. Since everyone is blindfolded, it presents a really different sport perspective for sighted players.”

That leveling of the playing field is what Simpson likes most.

“It’s a great way to include everybody,” he said. “It’s a very fun game that appeals to everyone and gives an opportunity to people who are visually impaired, who often miss out on recreational or sports opportunities. This is a great way to be inclusive across the board.”

After graduation, the 29-year-old Simpson – who is getting married in October – plans to work in general litigation and appellate practice at the Washington, D.C., law firm Sidley Austin. “Being able to be an advocate for people was a big appeal,” he said. “That really drives me.”

Simpson said his father – who has run the goalball program through the Georgia Blind Sports Association in Atlanta since 2001 – continues to be an inspiration.

“He’s still in the community, providing opportunities to young kids like I used to be,” he said. “He’s taken it and made it far more than just me, which is really cool.”

Four years ago, when the Braves played their final season at Turner Field, they invited Simpson to participate in the nightly ceremony that counted down the number of games remaining to be played in the venue. As part of the festivities, Simpson got to meet some of his heroes, including Pendleton, the former third baseman who he used to cheer for when he was a young boy.

“It was a very magical moment,” Hal Simpson said, “for the whole family.”

Media Contacts

Manager of Strategic Communications University of Virginia Licensing & Ventures Group

wdr4d@virginia.edu 434-982-3791