“It is pretty likely that he read the book, because we know he was present in Florence at this time, and we know of artists with whom he was in contact that had read and used it. A very good friend of his even owned a copy,” Fiorani said.

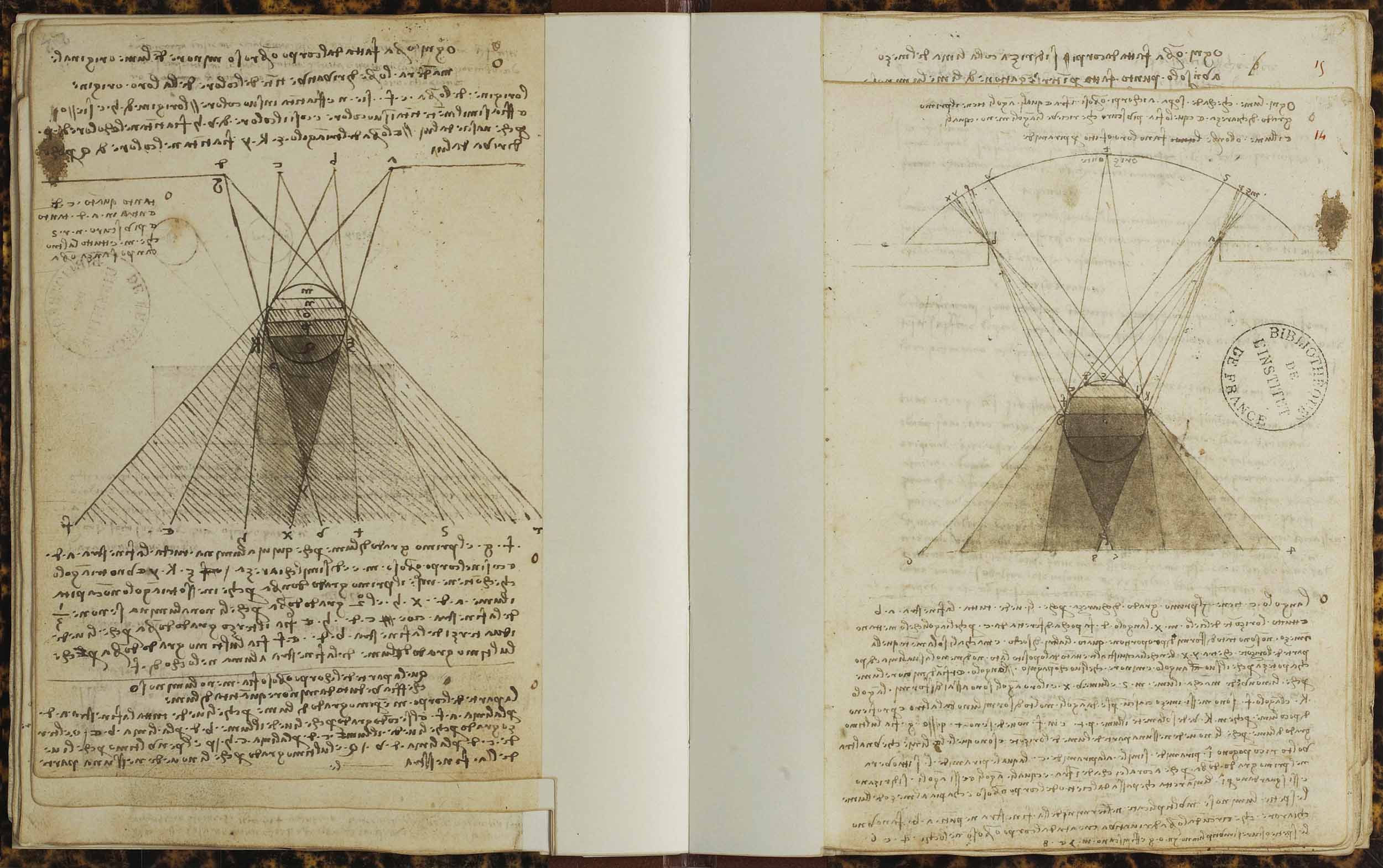

Plus, hints of the work abound in da Vinci’s drawings and journals, as he considered how to use variations of light and shade to capture what was going on in someone’s mind.

“If we imagine that he did read this book, suddenly we have an explanation of his art as a youth and throughout his life, an explanation of many of his writings, and why he was so interested in light, shadow, color and atmosphere,” Fiorani said. “We don’t have the ‘smoking gun,’ but conceptually, it’s very compelling. I am not the first one to suggest this, but I believe I am the first one to make the case as strongly as possible.”

It is possible, but difficult, to see the Mona Lisa without a crowd.

Because so much has been written about da Vinci, Fiorani is always working to keep herself grounded in the basics – in this case, the details of his work and everything she can observe firsthand about how he used light and shadow.

Of course, observing da Vinci’s work firsthand is no easy process; his paintings are among some of the most valuable and most closely guarded in the world.

“In order to study them the way I wanted to, I needed to see them without glass or frames,” Fiorani said. “I was able to do so for almost all of them – a work of years.”