As more than 100,000 Russian troops line the Ukraine border, tensions in Eastern Europe are growing by the day.

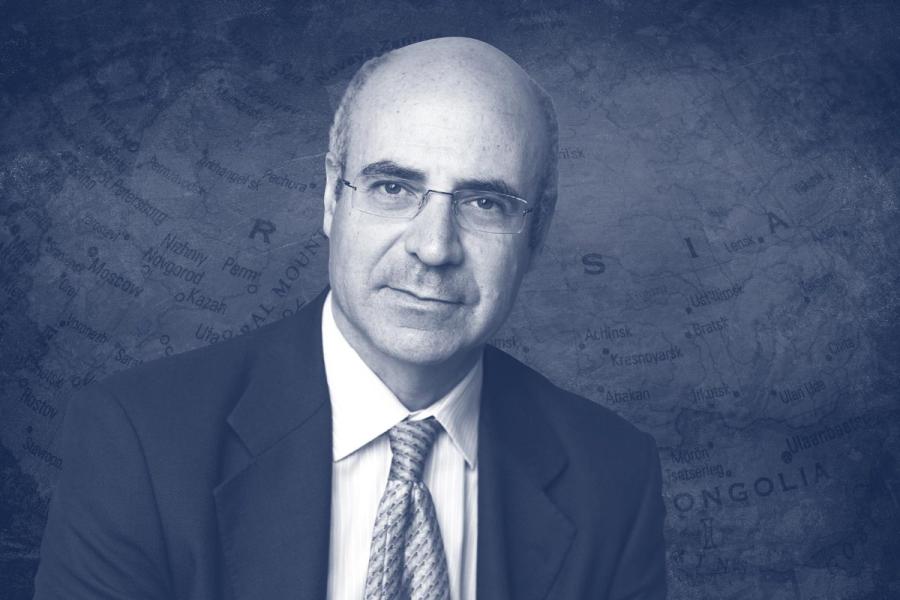

The building crisis, rooted in a fight for identity, could be nearing its tipping point. UVA Today turned to former U.S. diplomat Stephen Mull, University of Virginia’s vice provost for global affairs, for clarity on the situation, his thoughts on what could be coming next – and why Americans should pay attention.

Mull, who has held a variety of national security positions, was the U.S. ambassador to Poland from 2012 to 2015 under President Barack Obama and the U.S. ambassador to Lithuania from 2003 to 2006 under President George W. Bush. He’s currently a senior fellow at the Miller Center of Public Affairs.

Q. For those who are just starting to pay attention, what is the brief history of tensions between Russia and Ukraine?

A. Although its heritage goes back thousands of years, Ukraine didn’t become an internationally recognized independent state until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when more than 92% of its voters supported full independence. For the previous 1,000 years, the lands and tribes now constituting Ukraine were subject to foreign domination, from Mongol invaders and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the Middle Ages to Russian and Soviet control in more modern times.

Russian popular history holds that Russian identity was born in the small kingdom of Rus in the ninth century, where Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, lies today. Russian President Vladimir Putin has stated that Ukraine is not really a country, but rather an integral part of Russia, and that Ukraine’s growing aspirations to affiliate with the West pose a serious threat to Russia’s national security. The Ukrainian government, with the support of a large majority of its citizens, disagrees vehemently. That is at the core of today’s tensions.

Ukrainian governments have struggled during 30 years of independence to forge a single national identity, fighting severe challenges in governance and corruption, economic mismanagement and ethnic tensions between Russian and Ukrainian speakers. Those tensions have played out in competing visions for Ukraine’s strategic destiny, resulting in alternating governments that have pursued membership in the European Union and NATO and those who have sought tighter association with Moscow.

In 2008, the Bush administration prodded NATO to announce that former Soviet republics Ukraine and Georgia would ultimately join NATO. Russia invaded Georgia later that year, after which the new Ukrainian government of Viktor Yanukovych (2010-14) cooled the country’s drive to join NATO and instead concentrated on signing an association agreement with the European Union. When that agreement was ready for signature in late 2013, Russia successfully pressed Yanukovych to withdraw from the process, prompting a major popular uprising in Kyiv that drove Yanukovych into exile in Russia in February 2014.

Russia responded to Yanukovych’s fall by launching a hybrid war against Ukraine, including massive information operations aimed at destabilizing Ukrainian internal politics and the infiltration of unmarked mercenaries and special forces into eastern Ukraine to support Russian-speaking separatists. Russia also annexed Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula, which had been part of Ukraine since 1954, and offered quick Russian citizenship to Ukrainian Russian speakers, in a presumed tactic to justify further Russian military intervention in Ukraine, should it become necessary.

Russian forces continue to support Ukrainian separatists in eastern Ukraine, where a low-grade conflict with continuing casualties is about to enter its eighth year. This is despite Russia’s agreement in 1994’s “Budapest Memorandum” with Ukraine, the United States and the United Kingdom to guarantee Ukraine’s borders in exchange for Ukraine’s surrender of the nuclear weapons that were on its territory at the time of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

.jpg)