The news and images coming out of Afghanistan over the past week have been tragic, as Afghans – some of whom assisted American troops over the past two decades – have flooded Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, desperate to escape the dangers of Taliban rule as U.S. troops withdraw. Others have gone into hiding, and many more, especially many Afghan women, fear the loss of hard-won rights and freedoms.

As rapid as the Taliban’s advance has been this month – sweeping the country and the capital city in just nine days – these scenes are at least two decades in the making and many clues to their origins reside at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs.

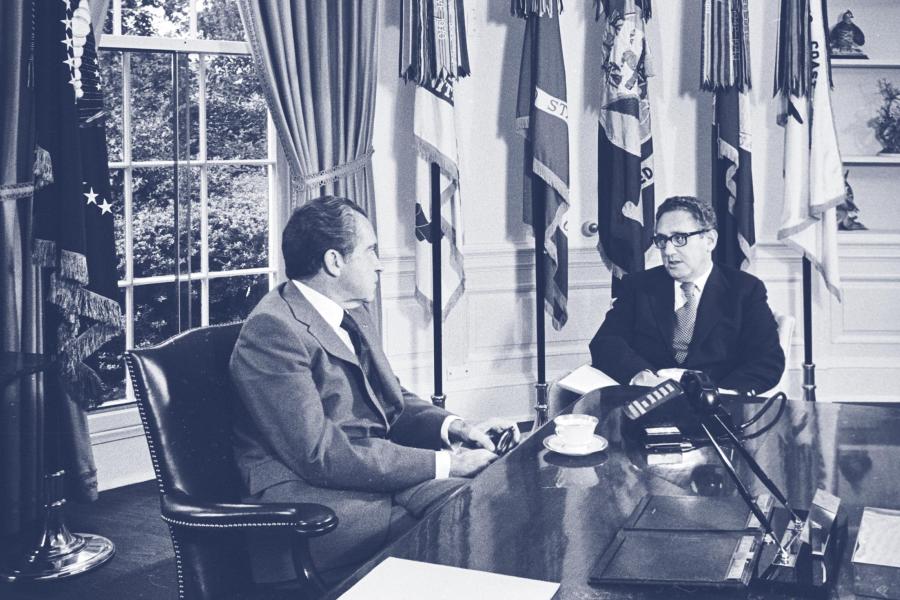

Home to the Presidential Oral Histories Project, the Miller Center has conducted comprehensive oral histories for every president since Jimmy Carter, with interviews for the two most recent administrations, those of Barack Obama and Donald Trump, still ongoing. Each one attempts to recreate life in the White House during that administration, “developing a portrait of the uncertainties, pressures and contingencies as they existed at the time,” as the program’s co-chair, Russell Riley, put it.

“This portraiture is exceedingly valuable for understanding what the job of the president is really like,” Riley said. “In the current circumstances, for example, it helps to understand Joe Biden’s decision [to withdraw troops] if you know how each of his immediate predecessors viewed this problem. You may still disagree with Biden, but it helps to know how frequently his predecessors have wrestled with the same issues – and contemplated actively the exact course he chose.”

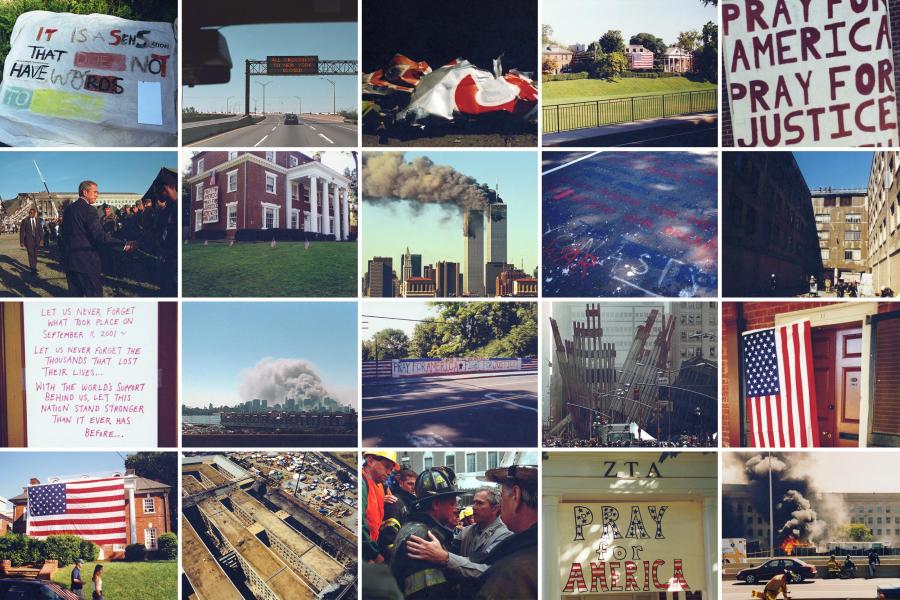

To get that understanding, scholars are turning to the George W. Bush oral history interviews, which include numerous firsthand recollections from advisers, politicians, diplomats and military leaders who were making the decisions at the time the U.S. entered Afghanistan in 2001, shortly after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“Because the Taliban had provided a known safe haven for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida, there was no question after the trauma of 9/11 that the United States would strike rapidly and aggressively there to seek retribution,” Riley said. “Our oral history interviews with senior Bush administration officials recapture both the agony of those early days after the attack and the palpable sense of urgency in taking action both to protect the American people and to claim justice for the victims.”