The economic conditions led to other problems, some of which still persist.

The division of Germany, coupled with the wartime depletion of the population, had created a labor shortage in West Germany at a time when the country was rebuilding and undergoing an economic resurgence. To solve this, West Germany brought in so called “guest workers” from around Europe and from Turkey, many of whom stayed and built lives there.

After reunification, “some East Germans raised questions about guest workers when they lost their jobs. In their minds, they weren’t competing with West German workers, they were competing, in their minds, for the jobs of the migrants,” Achilles said.

Achilles said guest workers and other immigrants experienced discrimination, of different types, in East and West Germany. Some of this discontent has also been directed at asylum-seekers and immigrants who have come to Germany in more recent years, leading to “hostile attacks on migrant communities,” she said.

European leaders at the time were wary of a reunited Germany and what tensions this might create, given the history of the 20th century, Achilles said. But she said Germany has worked on defining how it views itself.

“What is it that binds people of different backgrounds together and what sort of nationalism should it be?” Achilles said. “Germany is having this discussion now. For many West Germans, the answer is constitutional patriotism. They don’t like to talk about nationalism, or to use national flags and this kind of symbolism. The constitution and the values it defines are what bind the nation together, and this mechanism is open enough to bring in people with different kinds of heritages. As long as they are attached to the democratic constitution, people with different heritages and backgrounds can become Germans in this way.”

Geopolitical Legacy

The end of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany has had far-reaching effects on the world.

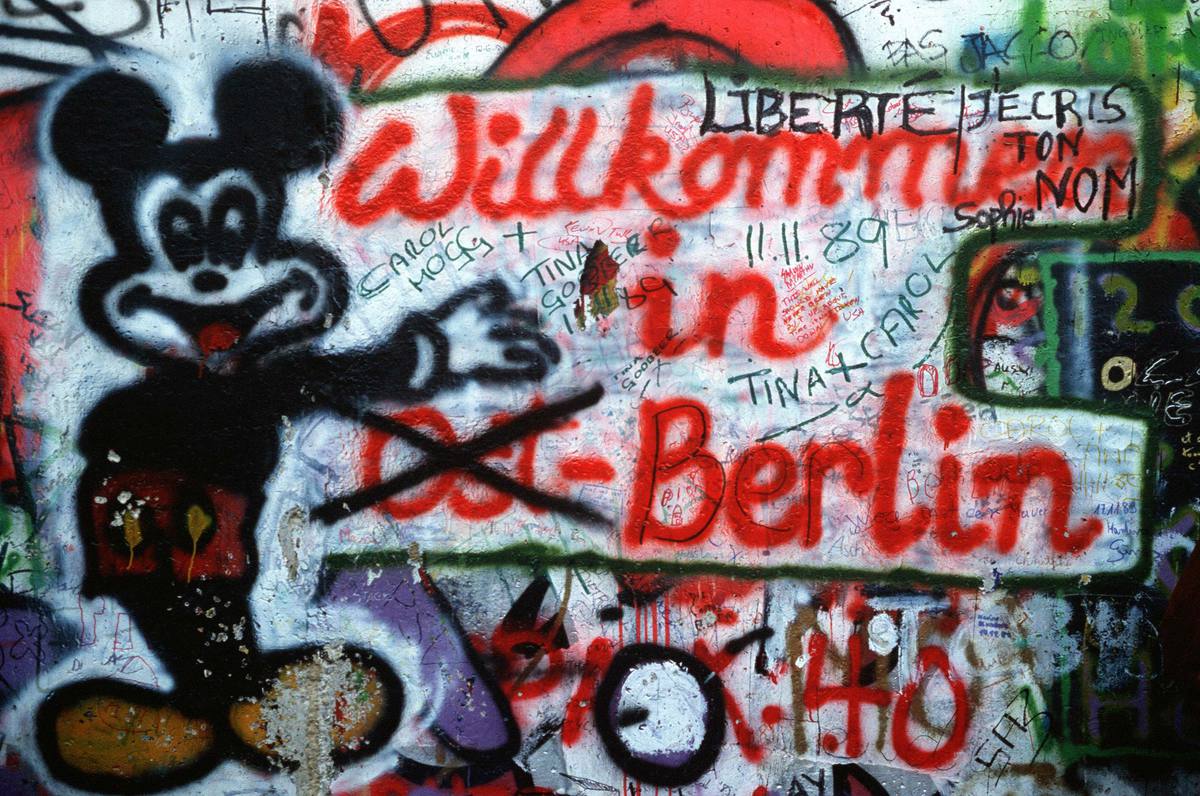

“The fall of the Berlin Wall is not just about Germany; it has changed the European Union,” Achilles said. “When the Soviet Union disintegrated, the East European countries … were integrated in the following years, this changed Europe tremendously. We see now that the new East European member states have a somewhat different agenda than the older members. ... It has made the idea of a progressive, further unification of Europe very complicated.”

Shirley views the fall of the wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union as one of the greatest achievements of the 20th century.

“It wasn’t the ending of the Cold War – it was the victory of the Cold War,” Shirley said. “Gorbachev gave up. The Soviets had gained ground through each U.S. president from 1917 up until 1980. They gained no ground against Ronald Reagan from 1980 forward. In fact, they start losing ground.”