Editor’s Note: Eighty-one years ago today, Allied Forces in Europe landed on the beaches of France and started a drive that ended a little less than a year later in Berlin. Two University of Virginia historians look back on this momentous event.

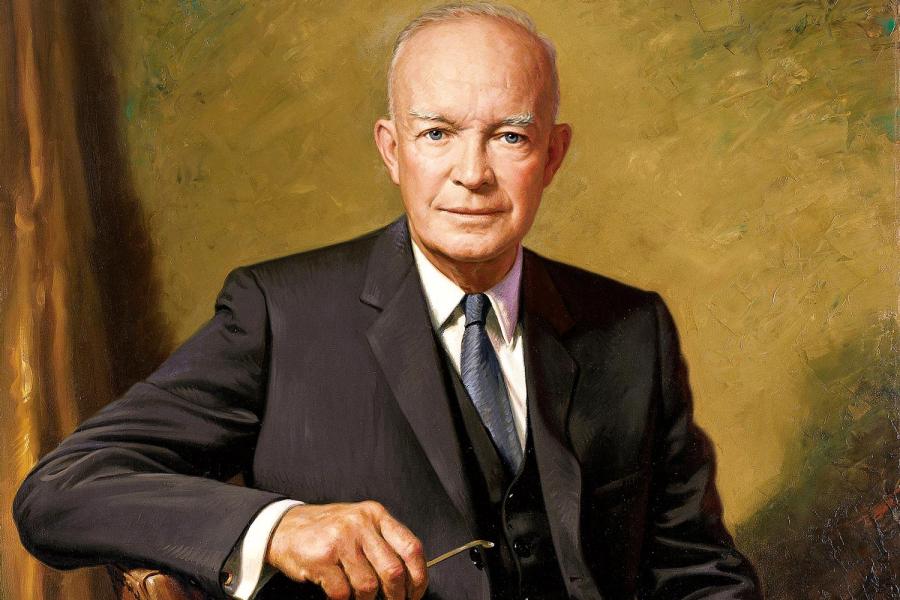

June 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Normandy, in German-occupied France during World War II. “D-Day” means different things in different places. In America, the operations of June 6, 1944 under the leadership of U.S. Army Gen. Dwight Eisenhower are remembered as a monumental invasion, the beginning of an unprecedented marshalling of men and material for a decisive strike on Normandy’s coast.

To the French, who were taken by surprise that day, it suggested liberation from the Nazis, but also opened up old wounds and new uncertainties. Jennifer Sessions, an associate professor in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History, specializes in European and French history and is author of the book “By Sword and Plow: France and the Conquest of Algeria.” She describes the Battle of Normandy as a time when farms, villages and shops became the battleground, all with the underlying fear that the Germans could turn the tide and resume their occupation.

History professors Jennifer Sessions, left, and William Hitchcock have studied different angles of the D-Day battle.

We spoke with Sessions and history professor William Hitchcock, author of “The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe” and “The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950s,” about D-Day, Eisenhower’s legacy, and the power struggles it set off in France.

Q. How did the D-Day invasion come about, and what was Eisenhower’s contribution?

Hitchcock: Older people overwhelmingly identify Ike as one of the great figures of the mid-century because of D-Day, because of the war. He is one of a very few for whom being president was not necessarily the most important thing in their lives. He really won his place in history in the European war.

D-Day was two years of preparation, but there are so many disagreements about it – and that is where Eisenhower’s talents really shone.

The British did not want to invade Germany from France; they thought it would be too difficult. This explains the North Africa landings, and the Italian campaign – all of that was the British insisting they should go through a softer approach.

The Russians were slaughtering the Germans. Privately, the British were delighted that the Russians, after Stalingrad, had got the upper hand and they were slowly grinding their way westward. The German/Russian campaign is so enormous, it is soaking up so much of the German resources, but they could never say that publicly because at the same time [Soviet Marshal Joseph] Stalin keeps saying, “Where is the second front? Why haven’t you opened a second front? Is this a conspiracy to let us do all the work?” There is a careful kind of dance going on.

[U.S. President Franklin D.] Roosevelt is in the middle of this because he wants to get onto the continent, but he needs the British to support the plan.

Eisenhower is very much the man to solve this dilemma. It is so much about his personal skills and reconciling very strong personalities. He has to be the mediator between Roosevelt and [British Prime Minister Winston] Churchill, between [U.S. Army] Gen. [George] Marshall and [British Field Marshall Lord] Alanbrooke, between commanders like [U.S. Army Gen. George] Patton and [British Field Marshal Bernard] Montgomery.

He is also the guy who has to generate a sense of purpose and unity and optimism, even though he doesn’t believe in the strategy he has been given, which is go to North Africa first and then fight in Italy and then eventually we will get to France. At every stage he says that’s a terrible idea, but he does it anyway. And this is a really important part of his biography – dealing with failure.

It is a big part of who he becomes. It’s not just the one day. It is the two years of work that goes into its shape, how he handles the rest of his career and his presidency, of dealing with failure, of dealing with the media on an almost daily basis, contending with big, powerful personalities who disagree. These are talents that have emerged during the war that become part of his career.

Sessions: For a lot of Americans, what was happening in Europe seemed like not really American business. American interest was more invested in the Pacific conflict, where the U.S. had been attacked by the Japanese, than it was in being involved in another European war. So with Churchill and Stalin and Roosevelt, it took a lot of lobbying to get Americans into the war in Europe. Roosevelt’s conviction that American public opinion needed to be prepared for it is one of the reasons that the D-Day invasion was postponed as long as it was.

Q. What were the elements of the invasion?

Hitchcock: The scale of the whole operation is so enormous, and Eisenhower is at the head of an enormous planning staff that is carrying out this incredibly complicated logistical feat.

There is a huge air campaign, but they can’t bomb just in Normandy because then the Germans will say, “Well, that’s where the Americans are probably going to land.” So they carpet bomb much of the coast, taking aircraft away from bombing the Germans in the battlefields and their factories. There are not enough airplanes to do it all, so they have to divert airplanes to bomb the coastline while not giving away the destination.

And there is an enormous intelligence component. There are deception operations in an effort to fool the Germans as to where they are landing. The U.S. creates an entire fictious army located in Britain that is supposedly commanded by Patton in a secret operation called “Fortitude.” And they are running phony radio traffic for this phony army to fool the Germans into thinking that Patton is going to land much further north.

There is the dimension of working with [French] resistance forces. Eisenhower brought a few resistance leaders in, but he could not tell them too much because he didn’t want the resistance to leak the information. So Charles de Gaulle is not informed about the invasion of his own country until two days before D-Day. And this causes endless grievances after the war.

Sessions: For people in the north of France, D-Day meant days, if not weeks, of bombardment prior to the landing. It meant close to 10 weeks of fighting in which their villages changed hands. The advancing Allies, because they had air superiority, were bombing from the sky. There were artillery bombardments as the Allies approach each town. Being liberated meant, for many people, being in the line of fire in very literal ways, and having to calculate if the Germans were driven out, were they going to come back?

There was uncertainty about what the Allies intended, because the French had not been part of the planning in any serious way, and at the very highest levels there was even discussion on the American side of installing an American government of occupation, similar to what they would end up doing in Germany. It didn’t come to much, and the American and Allied troops didn’t actually see themselves as an occupying army, but many of the French saw them as a potentially occupying force. And so there was a lot of uncertainty about what was going to happen.

Hitchcock: The biggest part of it is this gigantic naval operation with 6,000 boats of various kinds. They all have to be fueled and staged and get out of the English Channel and marshalled a few miles off the coast of France, and then they have to carry their soldiers onto a defended beach all at the same time. That dimension alone is enormous.

To get 150,000 men onto a hostile beach at the exact same minute after sailing across 19 miles of choppy English Channel was an immensely complicated operation. All of this power converges on a 50-mile beachhead. It takes incredible planning, and that is Eisenhower’s great characteristic talent. It reflects all of his skills, but this is what America is really good at.

The Americans come in with an incredible sense of planning and they invent so many specific tools for the job. They invent the Higgins Boats, which pop open to unload soldiers, tanks and trucks. It’s the triumph of invention put to use in a military campaign.

And that also reflects Ike’s belief in innovation and technology. He would go on to become the Space Age president; he would champion NASA and the space race and a whole generation of missiles and satellite technology. He was always looking for an edge. Even though in retrospect D-Day looks kind of old-fashioned, for 1944 it was amazing.

The Russians and the Germans are fighting on a front that is 1,500 miles long for most of a three-year period. Normandy beaches are only 50 miles from end to end. It all has to go exactly right or all of that stuff just gets pushed into a giant bottleneck.

Sessions: One of the things that you read in the memoirs of the American and British soldiers who landed in Normandy is that, “The French weren’t as happy to see us as we would have thought. The French were sullen.”

Really, the French were hedging their bets. They had been under German occupation in the north of France since June of 1940, and they had very direct knowledge of the consequences of perceived resistance to German occupation. Openly celebrating, openly assisting the Allies, which many people did do, was a potentially costly act, if things had not gone well.

Once the Allied forces were in France, there was a debate about liberating Paris or bypassing it. Eisenhower eventually let de Gaulle take a division of French forces to liberate the capital, but the French in some ways felt they had traded one occupier for another.

Q: What were some of the tensions that arose in France after the invasion?

Sessions: There was a lot of fighting about prostitution, which became rampant, and the American army was unwilling or unable to manage soldiers at the same time the French economy had been devastated by occupation and mass export of resources to Germany. For women especially, prostitution became one of the ways to survive. The equilibrium, however bad, that had been established during the war collapsed. There was a lot ground-level arguing about soldiers going off with women, in the alleys of northern cities and in people’s back gardens, and there was a lot of anxiety among French men about what that meant. Were the GIs, who were big and healthy and carrying cigarettes and chewing gum and chocolate, going to steal all the French women? There was a lot of ground-level tension.

Stars and Stripes [the U.S. military newspaper] covered the liberation of France with photos of American troops embracing and kissing French women, encouraging some of this tension. Occasionally there was a photo of a GI giving candy to kids, but mostly coverage is about France as this land of romance and opportunity. There is evidence that some of the GIs took them at their word and after the liberation of Paris, they called Paris ‘the Silver Foxhole’ because it was the glittering place full of entertainment, but also brothels, legal and illegal, and other opportunities to meet French women.

Media covering the war showed soldiers comforting children, as seen here, but also romanticized soldiers’ relationships with French women. (Photo: public domain)

There was also an internal power struggle between the external forces of de Gaulle and the Free French and the internal resistance, which was dominated by the French Communist Party. There was a struggle for power over who was going to control the post-war situation. So there was liberation from the Germans, but in the power vacuum, there was also quite a bit of violence and political tension.

Of all the political groups in France who could really claim to have fought fascism from day one, the only group that could do that unambiguously was the Communists, going back to the 1930s. Through the war the Communists were the largest and the most effective resistance force, particularly in the unoccupied zone. Part of that is that they were used to being organized in cells and operating clandestinely. Organizationally, they were in a good place to flip very quickly into resistance activity.

There was a short period of time at the end of the war and shortly afterward when people, especially in Central Europe, thought that communism was a viable alternative to the fascism under which they had been living with the Nazis and to the unstable governments that failed to stop the Nazis from rising to power.

Having lived through the tremendous instability of the interwar period and having lived through the First World War, which was living memory to many adults in Europe, the calculus looks really, really different than it did from the United States. By contrast there were people in the United States who thought that Hitler was better than Stalin.

Q. How is D-Day remembered today?

Hitchcock: I think D-Day is very much a touchstone for the American identity. A non-professional army of factory workers and schoolteachers got into uniform, they went to a place they didn’t know about and they fought the bad guys, and, using their skills and their talents and their cleverness, they overcame a much more powerful, demonic enemy.

There is nothing wrong in telling the story that way, but it compresses a lot of complexity. What I think is regrettable is that we miss the rest of the year. Because from June of 1944 to May of 1945 is a very long, hard year, and that is when most of the casualties in Europe will be lost.

Sessions: When the French step back and think about the bigger picture, it becomes ambiguous very quickly, because their liberators also brought destruction.

Everywhere there were difficult moral and political questions about collaboration and behavior during the occupation that were brought to the surface once the Germans were gone. It is a much more complex kind of story.

But you find it is much more complex when you dig into the American side as well. The mythologies never capture things that well. There is one thing that every historian says at least six times a day: “Well, it was more complicated than that.” That applies equally well here.

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

mkelly@virginia.edu (434) 924-7291