In her presentation to UVA Athletics, Stroman said, she focused on what she calls “awareness, understanding and application. My analysis is certainly built on people who’ve gone before me, but let’s name it so that we can face it. And so it’s not diversity training, it’s not implicit bias, it’s not cultural competence. This is about race and racism, and how we can better understand where we’re getting stuck.”

Stroman said she discussed the disparities among races, as well as “language, different words and terms that have evolved. I do a good part on the history, as in how we got to where we are today. And then I do some on culture, as in what is white culture, and how [that affects] white, brown and black people. Then I won’t say I tie a big bow around it, but that’s the initial presentation, to help us move forward from there.”

When she’s approached about a speaking engagement, Stroman said, “I tell them upfront: I’m not the one for you if you want me to come in and talk about the light stuff, about variety. We all know variety matters. We all know that the best ideas come from many ideas. I come in and talk about race and racism. And if you’re ready for that, then I’m all in. But if you want some light, watered-down version, ‘Kumbaya,’ I’m not the one.”

She smiled. “And that’s probably the Philly in me, right? I’m very direct.”

Stroman grew up in the Philadelphia area and graduated from Conestoga High School, whose alumni include another former UVA women’s basketball standout, Chelsea Shine. Stroman narrowed her college choices to two: Virginia and the University of California.

“I couldn’t decide between Berkeley and Virginia,” she said, “and at the last minute I chose Virginia because it was closer to home.”

On her recruiting trip, Stroman connected well with Val Ackerman, who’d joined the program in 1977. (Ackerman is now commissioner of the Big East Conference.) Once she enrolled at UVA, Stroman bonded immediately with fellow freshman Melissa Mahony, who’s still one of her best friends.

“They were like peanut butter and jelly,” Ryan recalled, “and their games complemented each other also. If we’d had a 3-point shot back then, Melissa would have been incredible with that.”

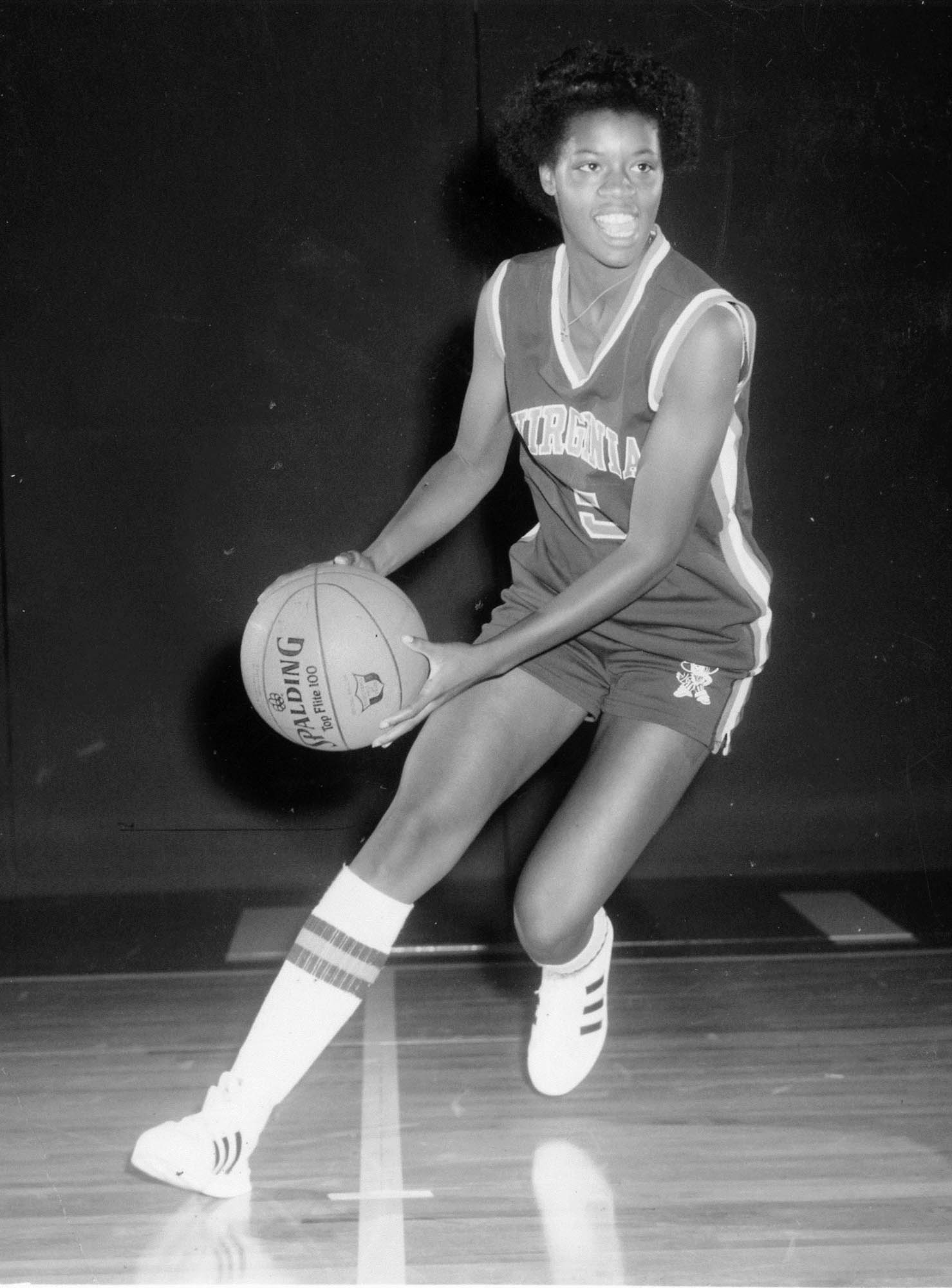

In 34 seasons under Ryan, the Wahoos won 739 games. Her first winning season, 1978-79, came in Stroman’s first year in the program.

“Debby was really the epitome of what you would want in a player,” Ryan said. “She was really someone who came and embedded herself here very quickly and got very, very comfortable in the program. She just loved the game and loved her teammates, all the way to this day. She’s sort of a rallying point for a lot of these women.”

In those days, the UVA women’s program had few resources, “so we were fighting for everything, but it didn’t bother Debby,” Ryan said. “She just went on, and really the fact that we shot up so quickly, some of that’s due to players like Debby and Melissa who recruited [other players] for me.”

Stroman remembers the emphasis Ryan placed on defense. “We used to joke back then that we were spending more time running on the cross country trail than the cross country team,” Stroman said, laughing. “When we were getting beat, we weren’t losing because we were tired. And so we did a lot of running. To this day, there are still times when I say, ‘Can I do this?’ and I look back and say, ‘With what you went through with Debbie Ryan and that running, you can do it.’”

Her undergraduate experience remains “collectively the best four years of my life,” Stroman said. “It was really a special time. My closest friends today all have UVA ties.”

UVA’s student body was less diverse then than it is now. Stroman encountered racism in Charlottesville and elsewhere, but her experience differed from that of the average African American student.

“As I talk about race and racism to people all across the country, the one thing I can say about my personal experience, even though I’ve lived [through bad] experiences, is I had the buffer of athletics,” Stroman said.

“I was living in two worlds at UVA. I had my community, primarily African American students, being in the [Zeta Phi Beta] sorority and being one of the leaders in the Black Student Alliance.” But she also spent considerable time with members of UVA’s basketball and football teams, all based in University Hall then.

“We were all close,” Stroman said, “And so I didn’t experience what a lot of my Black peers did.”

That’s not to suggest she ignored reality. “Now, I’m from Philadelphia, I grew up in a very race-conscious family, so I knew what was going on and I was involved,” said Stroman, who remembers marching on then-UVA President Frank Hereford’s house to protest apartheid in South Africa.

“I was very much an activist,” Stroman said. “I’ve been an activist all my life. But certainly I was not experiencing what some of my classmates were going through.”

After graduating from UVA with a bachelor’s degree in history and social studies education, Stroman worked for a year in the NCAA’s Volunteers for Youth program. Her travels took her to North Carolina’s Triangle area, where she learned that UNC was starting a master’s program in sport administration.

“And so I was in that first class,” Stroman said.

While in graduate school in Chapel Hill, Stroman was an assistant coach on the UNC women’s basketball team, which won the ACC title in 1984. Having to face Ryan and UVA “wasn’t as enjoyable as I would have liked,” Stroman said, “but that was a great ride as well.”

After earning her master’s degree, Stroman went to work in financial services and found she had a passion for sales. In 2003, she went back to school and four years later earned a Ph.D. in leadership and organizational behavior from Capella University in Minnesota. She returned to UNC in 2007 and began teaching, focusing on leadership, sport business, entrepreneurship and racial equity.

Given her ties to UVA and UNC, Stroman could have been uncomfortable when those schools’ men’s basketball teams met Feb. 20 in Charlottesville. Not so. To Stroman’s delight, the Hoos defeated the Tar Heels, 60-48, at John Paul Jones Arena.

It’s one thing for the average college student or alum to embrace a rivalry, “but it’s another one if you’re a student-athlete. So I was trained to hate Carolina. ‘ABC,’ right?” Stroman said, laughing.

For Hoos, of course, that stands for “anybody but Carolina.”

“I tell my students and my peers – and actually there are a lot of UVA grads who work here as faculty – that I win no matter what [when Virginia plays UNC], but my blood bleeds orange,” Stroman said.

A regular pregame guest on the radio broadcasts of UNC men’s basketball games, she has met UVA head coach Tony Bennett and many of his players. “Tony is very concerned, like a lot of great championship coaches are, about race relations,” Stroman said, “and so we’ve had some one-on-one conversations.”

Many of the friendships Stroman formed as a UVA undergraduate still exist today. In 2019, she was among the dozens of Virginia men’s and women’s basketball alumni who made the journey to Minneapolis for the Final Four, where Bennett’s team won the program’s first NCAA title.

“Bucket-list trip, for sure,” Stroman said.

About seven weeks later, many of those same alumni, at the invitation of UVA athletic director Carla Williams, convened in Charlottesville for the implosion of University Hall.

To see Mahony, brothers Ricky and Bobby Stokes, Dawn Staley, Ralph Sampson, Marc Iavaroni and others “was just special,” Stroman said. “But when they pressed that button [to take down U-Hall], I cried. And I was looking at some of my other friends, other teammates, other people, other athletes, and a lot of people we were crying. Coach Ryan was crying.”

On her trips back to Charlottesville, Stroman said, she’d always made a point of driving by U-Hall, a venue in which she’d spent countless hours. “And the fact is that I will never see it again,” she said. “So I think that’s why it was so emotional for me. It was a very, very powerful weekend, I’ll never forget it.”

She stopped playing basketball a couple of years ago – “It just too hard on my body,” Stroman said – but she stays active. “I ride my bicycle, I play golf, I lift a lot of weights. I walk, but no more hoops.”

Stroman picked up golf when she worked in financial services. She noticed that her white male colleagues “were all playing golf, and I said, ‘There’s something going on. This is more than going out there and hitting that white ball. It’s about getting all the scoop, the insights, creating bonds.’”

Not only did she become a regular on the course, Stroman teamed with another UVA graduate, Jandie Smith Turner, to found a company, Soulful Golf Inc., whose goal was to increase the participation of women and people of color in the sport.

Professionally, though, Stroman’s primary focus is racial equity. She noted that the late Derrick Bell, a Harvard Law School professor, argued that racism is permanent, and Stroman believes that can make a lot of sense for many, considering current and historical conditions.

“But that doesn’t mean you don’t fight it and you don’t struggle and try to make each day a better day,” Stroman said. “I’m hopeful.”