In politics, it feels like the lofty promises and plans that accompany elections all too often fail or sometimes vanish entirely.

At present, the Virginia Redistricting Commission looks like it might be facing such a fate.

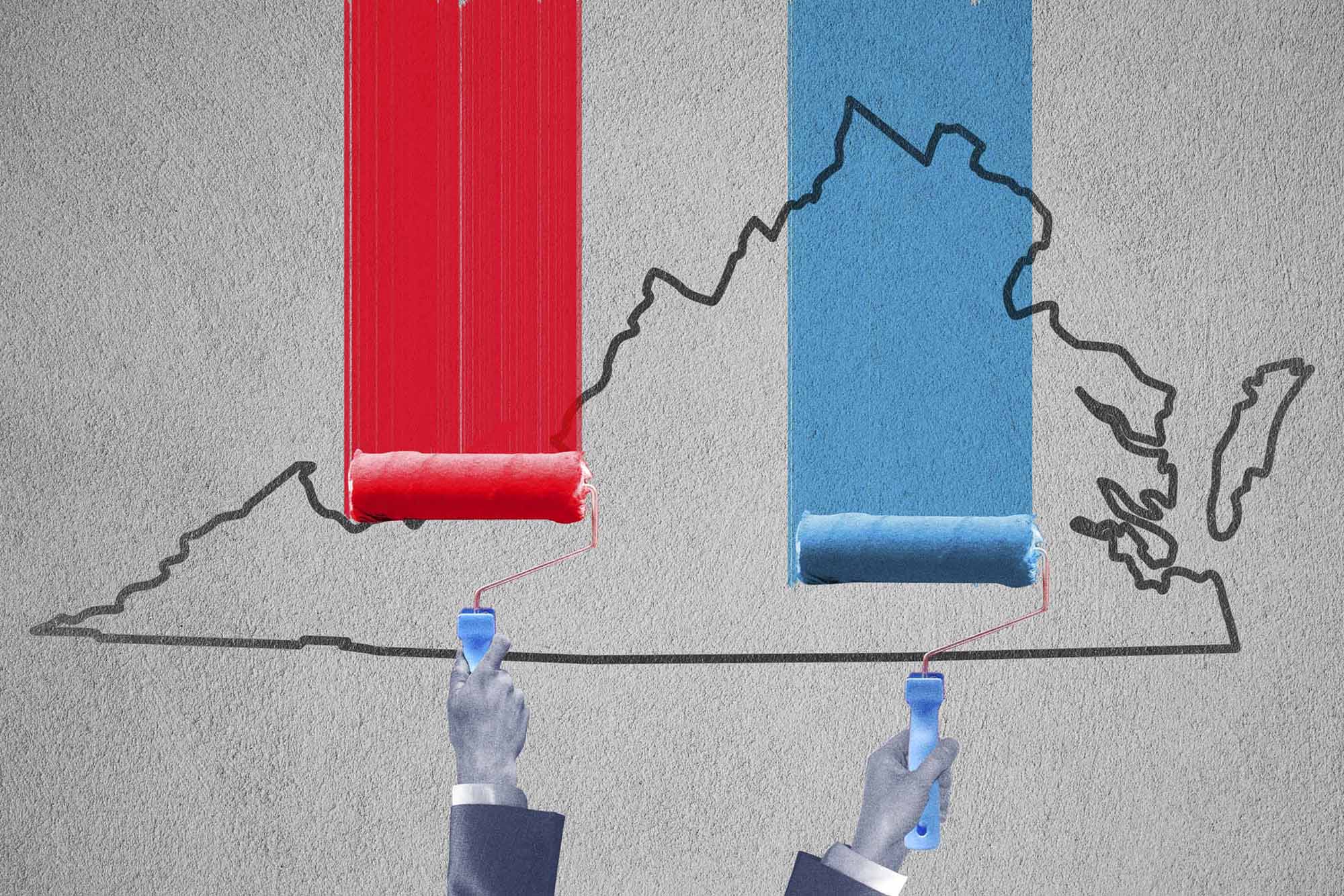

Created by a state constitutional amendment approved by voters in the 2020 election, the Virginia Redistricting Commission is tasked with drawing the district lines for Virginia’s 11 U.S. House of Representatives seats, as well as the Virginia General Assembly. District lines are reviewed and redrawn every 10 years, following the completion of the U.S. Census.

In the past, the General Assembly, like many state legislatures, redrew and voted on district lines. This frequently generated controversy and partisan bickering as the majority party controlled the process and thus the geography and makeup of the districts. UVA Today recently explored the broader redistricting process.

.jpg)