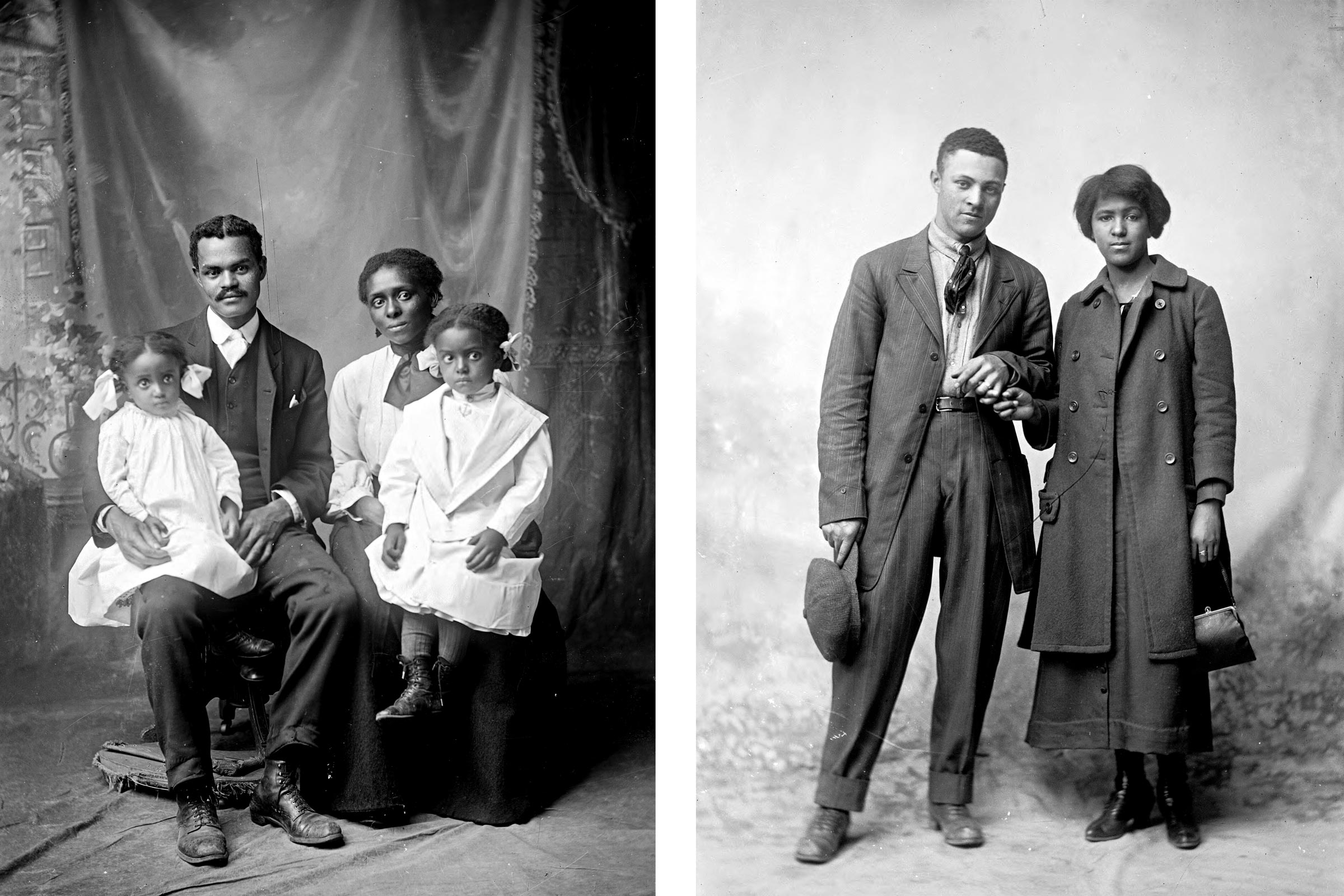

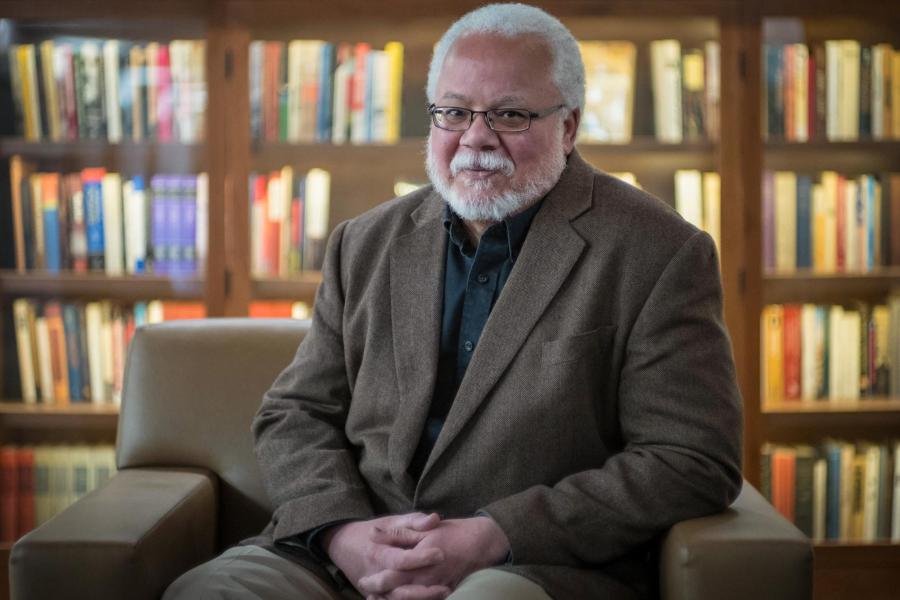

“These are beautiful images that open a window into the life of the black community that we really cannot get anywhere else,” said Mason, who teaches both African history and the history of photography. “We often read about the oppression and segregation these people endured, but they were not defined by that. Despite often tough circumstances, they lived lives of dignity, joy, love, community and family – we can literally see that in these images.”

Mason, working with the UVA Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities director and computer science professor Worthy Martin and several others from UVA, Monticello and Charlottesville, are planning a series of events and exhibitions to highlight Holsinger’s images – some of which have been exhibited before, and others being shown for the first time. In February, they were awarded an Arts & Sciences Diversity and Inclusion grant to fund outdoor displays of the portraits in and around Charlottesville.

Their plans include a display on the construction fencing around the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which broke ground in January. The location – east of the Rotunda between the Lawn and the Corner – ensures that scores of students, faculty and staff will walk past the photos on their way to class and work.

Mason and Martin are also eager to bring the photos into the larger Charlottesville community, and to bring community members into their analysis.

On Saturday March 9, they hosted a “Family Photo Day” at the Jefferson African American Heritage Center. There, local residents could review photos in the collection and identify or provide more information about family and community members they recognize.

A professional photographer was on hand to take new family portraits in Holsinger’s style, and residents could bring in their own historic photos for authentication.

“There are names attached to many photos, but we do not know much more than what census or tax records can tell us – and in some cases, we do not have a name at all,” Mason said. “We are hoping descendants can tell us more about these people; not just their name, but their stories, their personalities.”

Large as the University’s collection is, it only represents about half of Holsinger’s total output, and does not contain images captured before 1912, when his studio burned down. Some of those earlier images could be tucked away in homes, attics and basements throughout Charlottesville. Already, Mason has received emails about a few photos, including at least one that was taken by Holsinger and passed down through a local family.

Holsinger’s distinctive style makes his portraits recognizable even today. They are typically posed in his studio, often featuring props or outfits that the subjects chose themselves. Those choices, Martin said, offer some insight into people’s individual interests and personalities.

“They are so evocative, it really feels like someone is reaching through the camera to tell you who they are, and how they want to project themselves, as opposed to how they might have been viewed on the streets of Charlottesville,” Martin said.

Martin and Mason hope the photos will remind viewers that African-American communities at the University and in Charlottesville have a rich, complex and often untold history.

“These images are bringing a new way of seeing Charlottesville and its history onto the landscape, so that people can encounter that new story on a daily basis,” Mason said. “We want to do the hard work of looking critically at that history, and providing context around where these people lived, where they worked and who they were.”

Image at top: Bill Hurley, 1909. Rufus W. Holsinger Photo. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.