__________________________

Notes

1. “Kasper Says Will Run Human Relations Council Out Of Town,” Charlottesville Daily Progress (hereinafter cited as CDP), 24 August 1956, 3. Kasper was head of the Seaboard White Citizens Council. There were four cross burnings in Charlottesville during 1956, “Fourth Cross Burned On Charlottesville Lawn,” The Washington Post and Times Herald (hereinafter cited as WP), 9 December 1956, B6.

2. Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Va., 103 F.Supp. 337 (1952); Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1976), 499-500.

3. For divisions among whites, see Dan Wakefield, “Charlottesville Battle, Symbol of the Divided South,” The Nation, 183 (15 September 1956), 210-213; Paul M. Gaston, Coming of Age in Utopia (Montgomery, AL: New South Books, 2010), 184-186. On the threats to Boyle and her allies, see Kathleen Murphy Dierenfield, “One ‘Desegregated Heart’: Sarah Patton Boyle and the Crusade for Civil Rights in Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 104(1996):251-284.

4. Benjamin Muse, “Why Charlottesville Is a Racial Test-tube,” WP, 22 July 1956, E1; Interview with George R. Ferguson, 4 December 1975, Charlottesville, VA; Interview with Oliver W. Hill, 5 October 1976, Richmond, VA; Interview with S.W. Tucker (quote), 19 September 1974, Richmond, VA .

5. “Speech of J. Segar Gravatt of Blackstone, Virginia Before The Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties, Charlottesville, Virginia, July 23, 1956,” reprint in the Donald R. Richberg Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 49 (quote); “Mass Meeting Backs Proposal To Ignore Integration Orders,” CDP, 24 July 1956, 1.

6. James H. Hershman Jr., “A Rumbling in the Museum: The Opponents of Virginia’s Massive Resistance (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1978), 251-253; Wakefield, “Charlottesville Battle,” 212. Richmond editor James J. Kilpatrick added fuel to the fire, “Alternatives in Charlottesville,” Richmond News Leader (hereinafter cited as RNL), 8 August 1956, 12.

7. Tom Hawley, “22,288 Sign Petition Against Integration,” RNL, 31 August 1956, 1; “Text of Darden’s Statement,” WP, 2 September 1956, A14; Robert E. Baker, “Va. U. President Testifies Against Stanley Plan,” WP, 6 September 1956, 1.

8. Ferguson and Hill interviews (quote); “Brief Case Believed Secret Hiding Place Of Tape Recorder,” CDP, 17 May 1957, 1. E.J. Oglesby, at the time vice-chairman of the Albemarle County School Board, predicted Charlottesville schools “will never be integrated,” “Charlottesville Official Vows No Integration,” WP, 14 August 1957, A15.

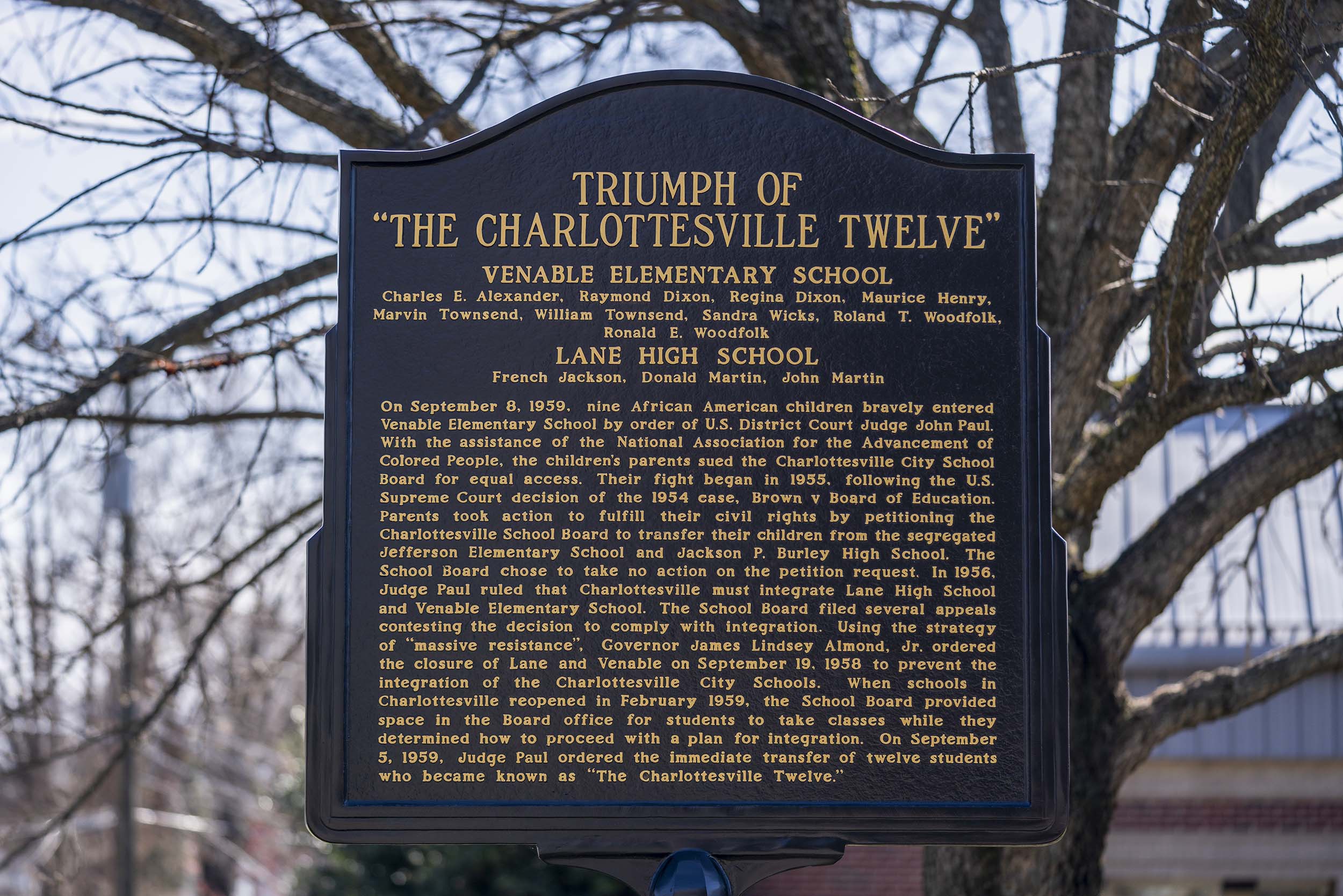

9. “Integration Set In Virginia Area,” The New York Times (hereinafter cited as NYT), 13 May 1958, 1; “Judge Paul Refuses Blanket Approval of City School Plan,” CDP, 27 August 1958, 1. The sequence of actions is outlined in Dodson v. School Board of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (1961), 441.

10. Andrew Lewis provides an excellent discussion of PCES and its role in his essay, “Emergency Mothers: Basement Schools and the Preservation of Public Education in Charlottesville,” in The Moderates’ Dilemma: Virginia’s Massive Resistance to School Desegregation, ed. Matthew D. Lassiter and Andrew B. Lewis (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1998), 72-103; Anthony Lewis, “ ‘Private’ Classes Directed To Stop Using Virginia Aid,” NYT, 9 October 1958, 1; Hershman, “A Rumbling in the Museum,” 308; a series of editorials and Letters to the Editor in the RNL offers perspective on the private school effort, “Random Notes on Private Schools,” 29 September 1958, 12, “Purposes of Charlottesville School Groups Vary,” 4 October 1958, 8, and “An Answer in Private Schools,” 10 October 1958, 10.

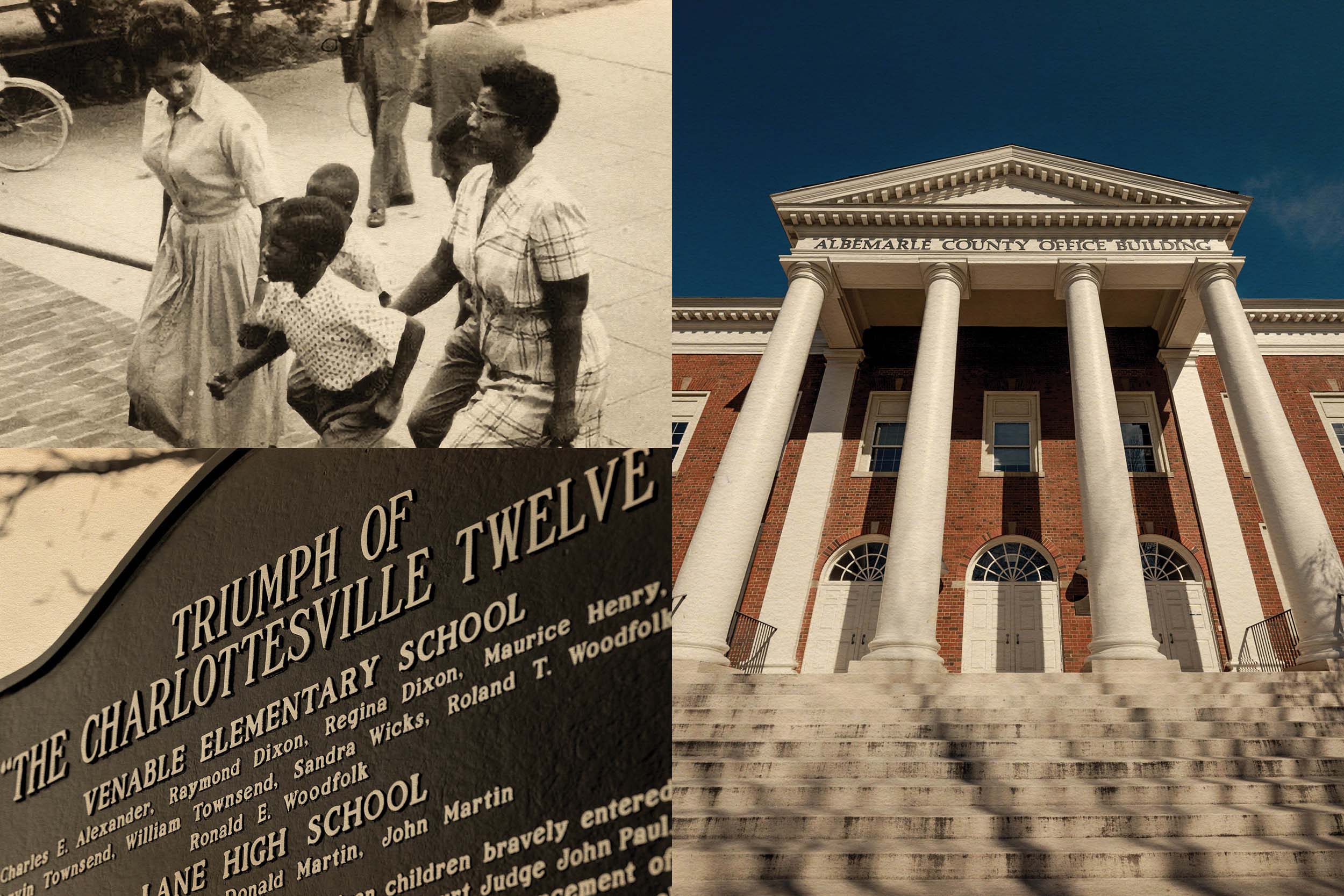

11. Lewis, “Emergency Mothers,” 88; Hershman, “A Rumbling in the Museum,” 305-6; Interview with Dr. James Bash, 15 April 1972, Charlottesville, Virginia. Susan McBee’s story, “University Remote From School Furor,” WP, 22 September 1958, B1, presents facts contradictory to the title. The article indicates the faculty was clearly affected by the school closings.

12. Charlottesville School Board v. Allen, 263 F.2d 295 (1959); James H. Hershman Jr., “Massive Resistance Meets Its Match: The Emergence of a Pro-Public School Majority,” in The Moderates’ Dilemma, ed. Matthew D. Lassiter and Andrew B. Lewis (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1998), 118-119; Don Devore, “Integration At Lane, Venable Carried Out Without Incident,” CDP, 8 September 1959, 1; Lisa Provence, “On Brown’s 50th: Why Charlottesville’s Schools were closed,” The Hook, 8 April 2004.

13. Hershman, “Massive Resistance Meets Its Match,” 127-128; Ted McKown, “When Is a Private School Public? Forum Argues ‘Free Choice’ Plan,” CDP, 20 February 1959, 17.

14. Robert E. Baker, “Economic Peril Cited In Closing of Schools,” WP, 11 December 1958, A17. See also, James H. Hershman, Jr.,”James M. Buchanan, Segregation, and Virginia’s Massive Resistance,” Institute for New Economic Thinking, 8 November 2020.

15. James M. Buchanan and G. Warren Nutter, “The Economics of Universal Education,” Report of the Thomas Jefferson Center for Studies in Political Economy, February 10, 1959, copy in Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA ; articles by Nutter and Buchanan in the Richmond Times-Dispatch: “Different School Systems Are Reviewed,” 12 April 1959, D3; “Many Fallacies Surround the School Problem,” 13 April 1959, 7. A proposal, the Wheatley Resolution, to remove constitutional protections for public education was introduced on 9 April and defeated on 20 April 1959, Robert E. Baker, “State’s Control of Education Would Be Ended,” WP, 10 April 1950, D1; “Segregation Bill Loses In Virginia,” NYT, 21 April 1959, 25.

16. “’Defenders’ Chief Heads Pupil Board,” WP, 26 July 1960, B2; Bash interview. In 1963, the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors removed Oglesby as school board chairman in a policy dispute, “Albemarle Reinstates 2 School Men,” WP, 12 July 1963, A5.

17. “Dean Sees Tuition Grants As A Necessary Expedient,” CDP, 22 July 1959, 15; Interview with Ralph W. Cherry, 20 April 1972, Charlottesville, Virginia; “CEF to Launch Fund Drive, Leon Dure is Chairman,” CDP, 20 April 1960, 13; Gaston, Coming of Age, 187; Griffin v. State Board of Education, 256 F. Supp 1178 (1969).

18. Allen v. School Board of Charlottesville, 203 F. Supp. 225 (1961); Interview with S.W. Tucker. Mr. Tucker was the lead NAACP attorney in the cases after 1959. Brian J. Daugherity, Keep On Keeping On: The NAACP And The Implementation Of Brown v. Broad of Education in Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 105-146.