It’s an inconspicuous spot: a rocky outcropping next to a Walgreens pharmacy, in the midst of a quiet residential neighborhood.

Researchers now know that Proctor’s Ledge was one of the most conspicuous spots in Salem, Massachusetts more than 300 years ago: the site where 19 accused witches were executed during the notorious Salem Witch Trials.

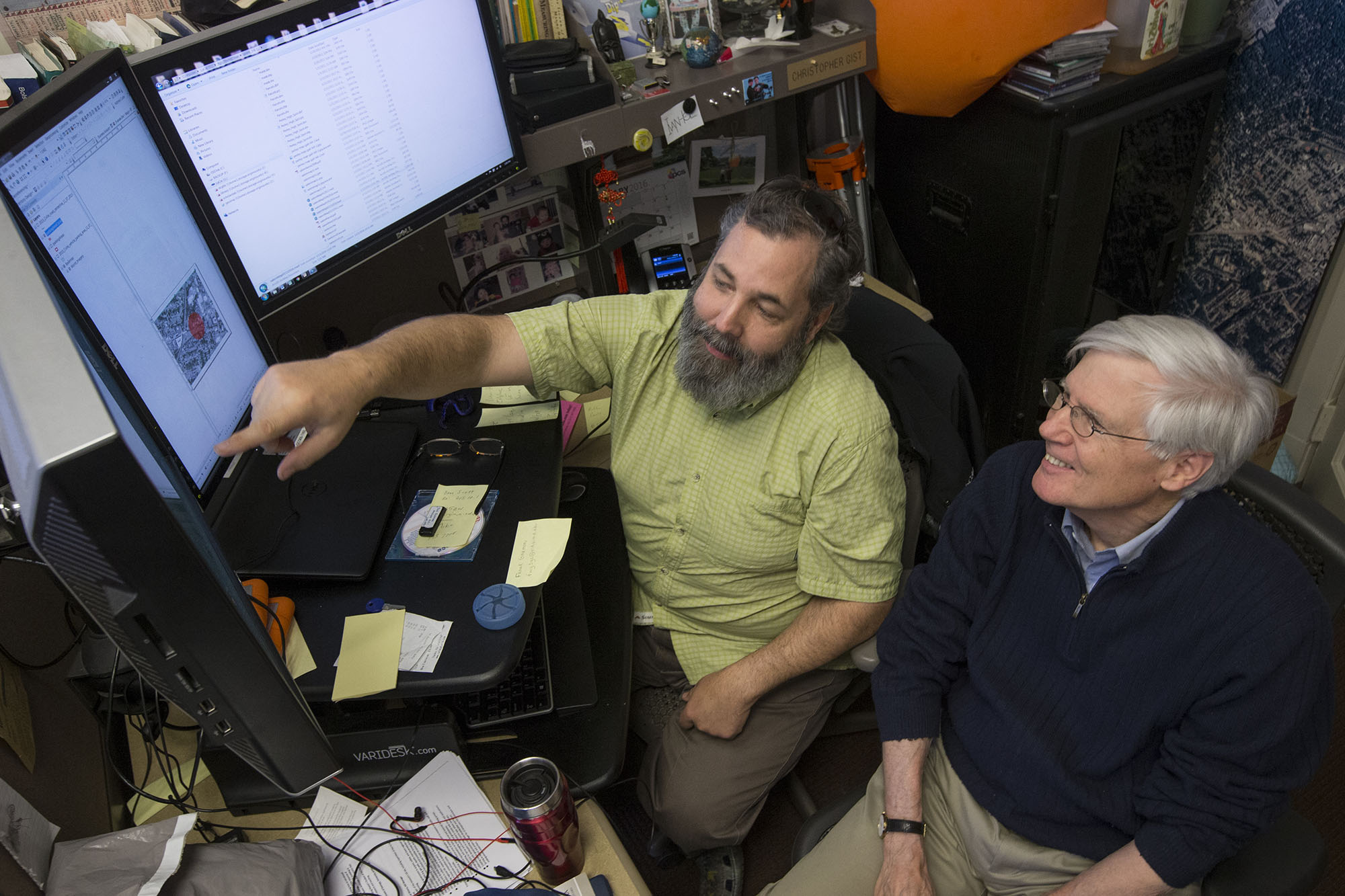

University of Virginia religious studies professor Benjamin Ray is one of five researchers leading the Gallows Hill Project, which announced its discovery last week to significant national attention. Ray, author of “Satan and Salem” (University of Virginia Press, 2015), oversees UVA’s Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, the most comprehensive digital archive of primary source materials from the trials. He worked with Chris Gist, a Geographic Information Systems specialist in Alderman Library’s Scholars' Lab, to digitally map the area and help confirm earlier research pinpointing the execution site.

Chris Gist, left, and Benjamin Ray, right, used geographic information systems technology in UVA’s Scholar’s Lab to help identify the execution site in Salem. (Photo by Dan Addison)

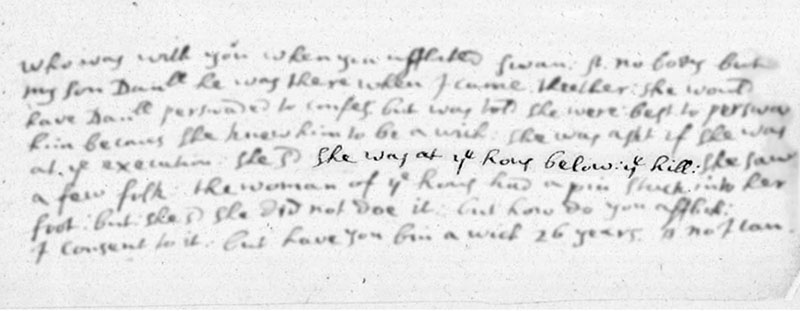

To identify the site, the researchers combed through maps, court documents and other primary sources, hoping to determine the location of “the house below the hill.” That phrase, discovered among nearly 1,000 pages of court records by researcher Marilynne Roach, was uttered by 51-year-old accused witch Rebecca Eames during her preliminary examination on Aug. 19, 1692. The magistrate asked if she had witnessed the five executions that occurred earlier that day and Eames responded that she was at “the house below the hill” when she saw the executions. (Appropriately, one of those executed that day was 60-year-old tavern keeper John Proctor. Proctor’s Ledge was named after one of his descendants).

The phrase “the house below the hill,” mentioned by Rebecca Eames as the place where she witnessed the executions, gave researchers a valuable clue that eventually led to the execution site.

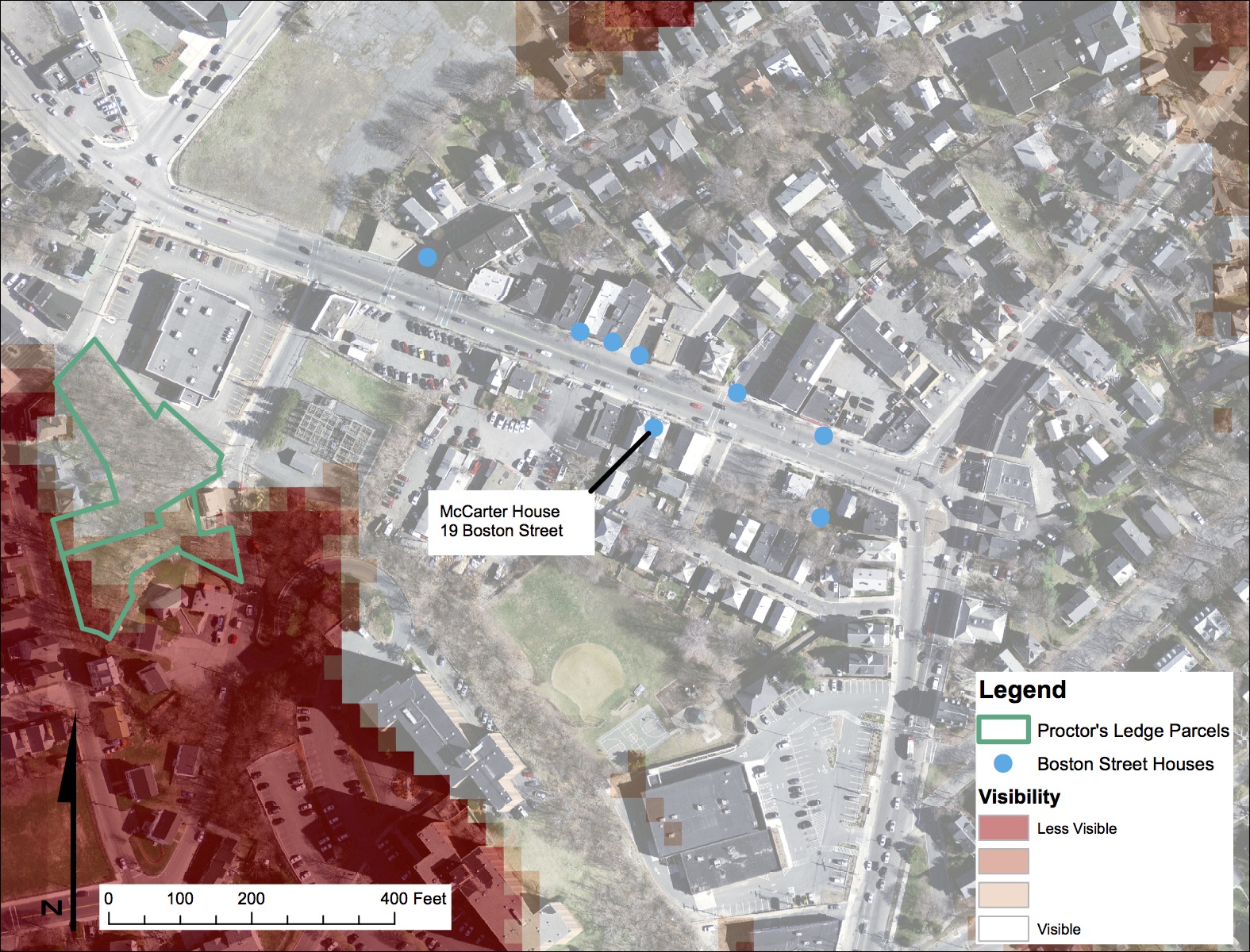

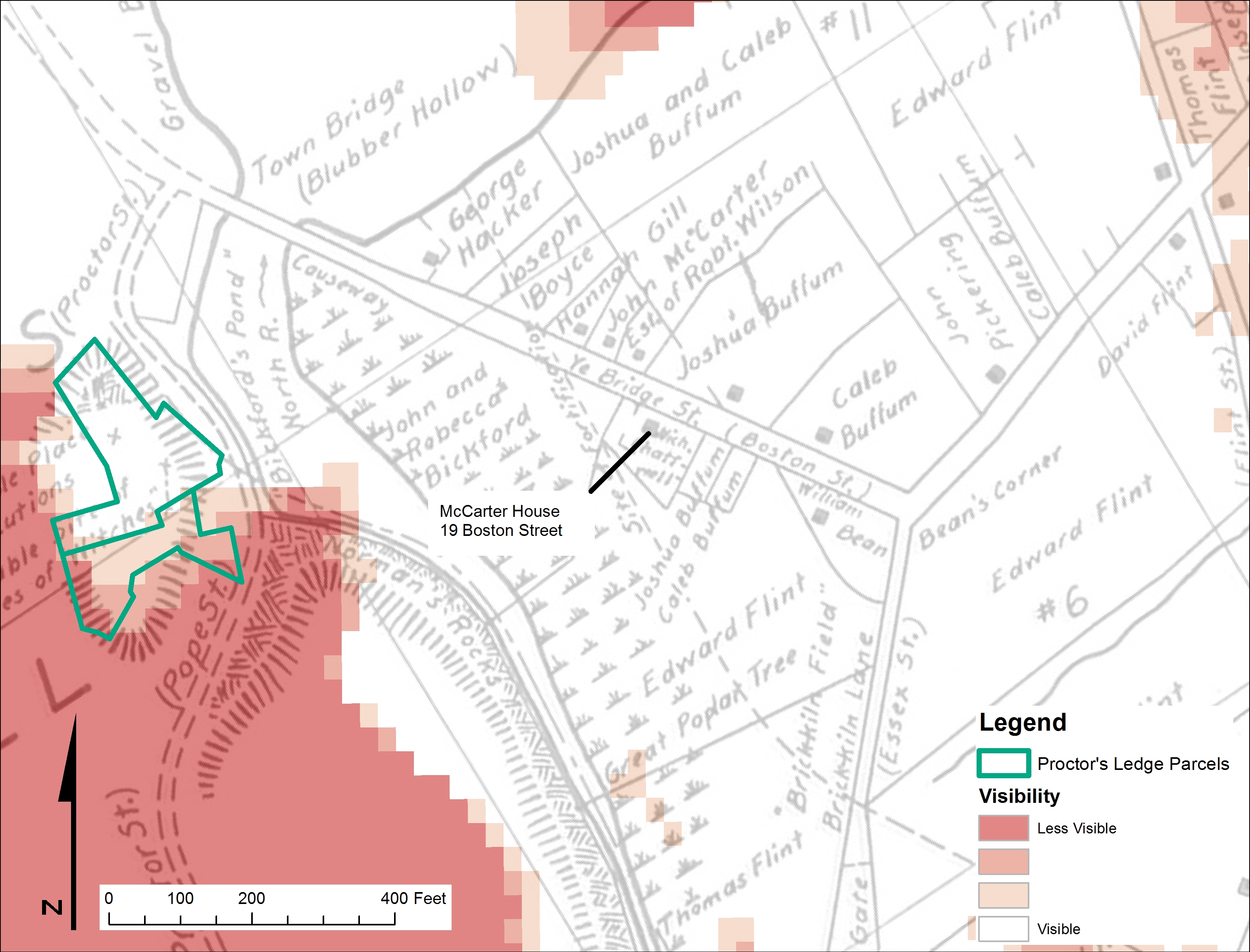

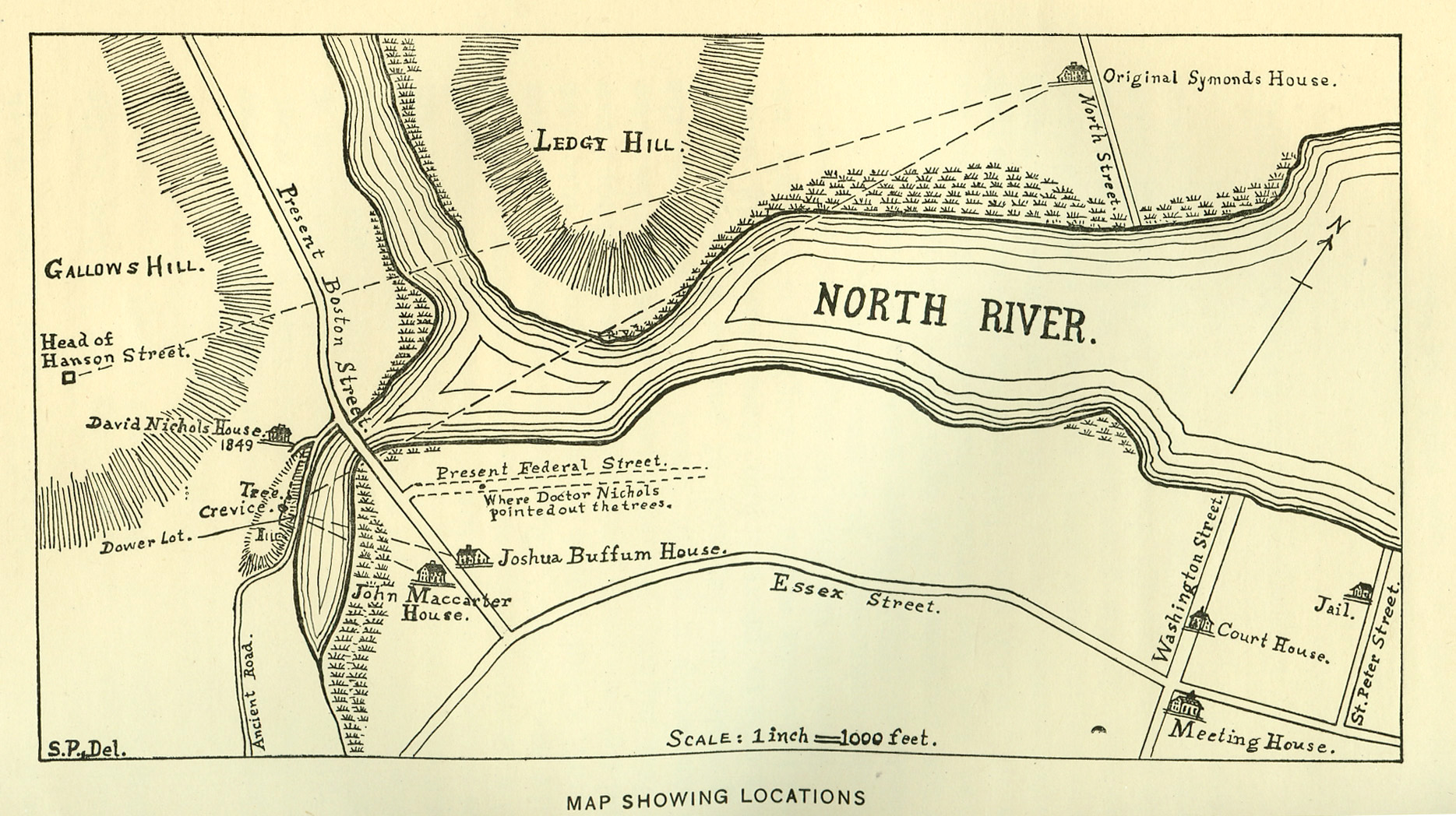

The team determined that Eames was referencing a house on Boston Street, most likely the house owned by the McCarter family. Boston Street was the main road that led into the courthouse and was across from several acres of public land, now called Gallows Hill. Researchers knew the executions took place on Gallows Hill, but they did not know exactly where.

A map of Salem in 1692, drawn by historian Sidney Perley, shows Gallows Hill, Boston Street and the John McCarter House. Perley identified Proctor’s Ledge as a possible execution site.

To find out, Ray and Gist analyzed maps of Salem drawn by early 20th-century Salem historian Sidney Perley, using technology that Perley lacked – the geographic information system software in UVA’s Scholars' Lab. The Scholars' Lab, which includes GIS specialists, has expanded rapidly over the last eight years to provide digital mapping resources to projects across Grounds.

“GIS really crosses all disciplines,” Gist said. “Anything that is spatial can be leveraged using GIS, and it can contribute to research in history, religious studies, politics, environmental science, architecture and many other disciplines.”

Using current topographical analysis, historical maps and aerial photos, Gist created a viewshed analysis of the topography surrounding Boston Street and Gallows Hill to determine which ledges on the side of the hill would have been visible from the houses on Boston Street.