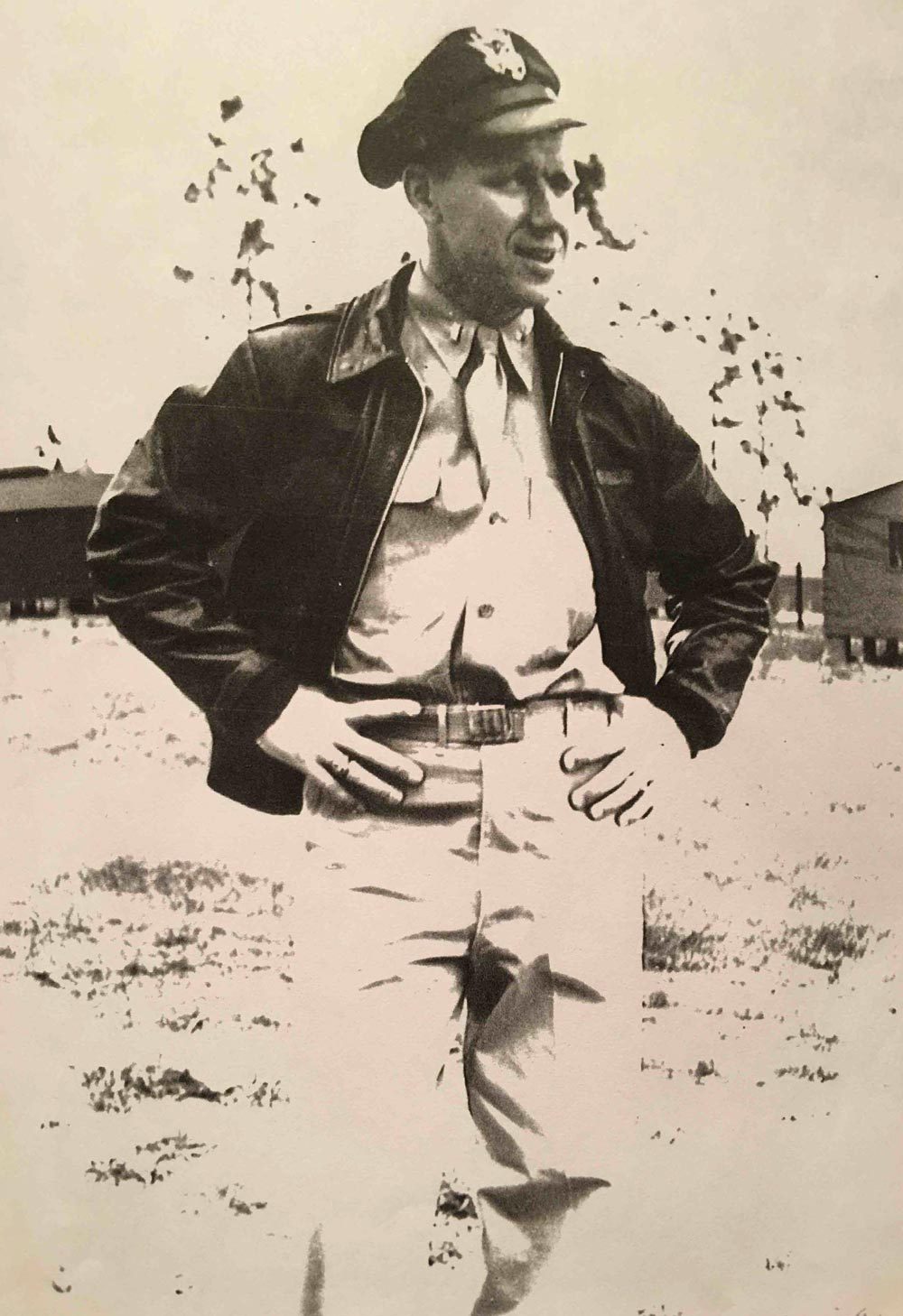

War Hero, Recipient of France’s Legion of Honor

UVA football fans may recognize Jack Bertram’s name. During the Nov. 23 game with Liberty University, a ParadeRest shout-out video detailing the veteran’s extraordinary military contributions was shown on Scott Stadium’s Hoovision screen.

As the song “Stars and Stripes Forever” played in the video, scrolling text told Bertram’s story. Born on Veteran’s Day in 1920, the B-17 pilot served in the 412th squadron of the 95th Bombardment Group. Based in England, Bertram flew into the history books by leading 36 combat missions over Europe.

“B-17s had the highest mortality rate, the highest injury rate and the highest capture rate of any military personnel during World War II,” Saathoff said.

Because of this, the military capped any one crew’s number of missions at 35. “It felt like the way to keep crews together was to say, ‘Look, if you can make 35, you don’t have to fly another mission,’” he said. “Each one was really death-defying, and Jack flew 36.”

The video played to thunderous applause in Scott Stadium.

Among Bertram’s flights was a special mission over German-occupied France. Bertram and his crew dropped two large containers of arms and ammunition to members of the French resistance, a move that was recognized in June 2013 when Bertram received France’s Legion of Honor, the nation’s highest decoration.

On Mission to Munich, “The Sky Blackened”

Talking quietly Tuesday evening in the parlor before the Virginia Gentlemen performed, Bertram recalled another mission, one that took him and his crew to Munich and nearly ended their lives.

Flying out of an airfield in East Anglia, England, Bertram maneuvered his plane, flying in large circles to reach an altitude of 17,000 feet and rendezvous with the other bombers headed to Munich. “You start from 17,000 feet in formation with your group and fly up to 25-, 26- or 27,000 feet, depending what wing you are in,” he recalled.

“When we got to Munich, the shrapnel was extremely heavy,” he went on. “The sky blackened and we went in and dropped the bombs.”

Shortly after the crew closed the bomb bay doors, the B-17 took a direct hit, scattering shrapnel everywhere. The hit knocked out the inboard engine on the left side of the plane, seriously wounding a waist gunner.

“We immediately dropped out of formation because we also lost all our turbos,” Bertram said calmly. “So, we lost a lot of power and we just started down. We had to go down anyway, because our oxygen was destroyed. You can’t stay up without oxygen more than a minute or two.”

So, Bertram lowered the plane to about 5,000 feet and had to decide whether to try to get back to East Anglia or go to Switzerland, which was much closer to Munich. If they’d flown to the neutral country, Bertram and the crew would have been interned. “I just had a few minutes to make a decision. I made a decision to try and get back.

“I said a prayer that we didn’t meet any German fighters on the way back. Through some blessing, we made it all the way back and got down,” he said.

For Saathoff, honoring Bertram, a huge UVA sports fan, was joyous. “He’s just an extraordinary guy and very, very humble,” he said.