Following the original festival, the counterculture swelled with ecstatic talk about peace, love and understanding, and the formation of the “Woodstock Nation.” It was the age of the hippie and pious optimism.

Then came Altamont.

On Dec. 6 of the same year, the Rolling Stones – filled with the hubris of completing a profitable U.S. tour – wanted to give a free show in California. The proposed venues started with the Golden Gate Park, then shifted to the Sears Point Raceway and eventually to the Altamont Raceway, which hosted motorcycle races and demolition derbies. The Rolling Stones invited several California bands, with the Stones themselves scheduled to close out the show. They also hired the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang to sit on the stage and keep the crowd back. They paid them with $500 worth of beer.

By the time the one-day show was over, four people were dead; two killed by a hit-and-run driver, one drowned in a ditch and one, Meredith Hunter, stabbed and beaten to death by the Hell’s Angels.

There was no 25th anniversary concert to mark Altamont. There are no plans for a 50th anniversary celebration this year.

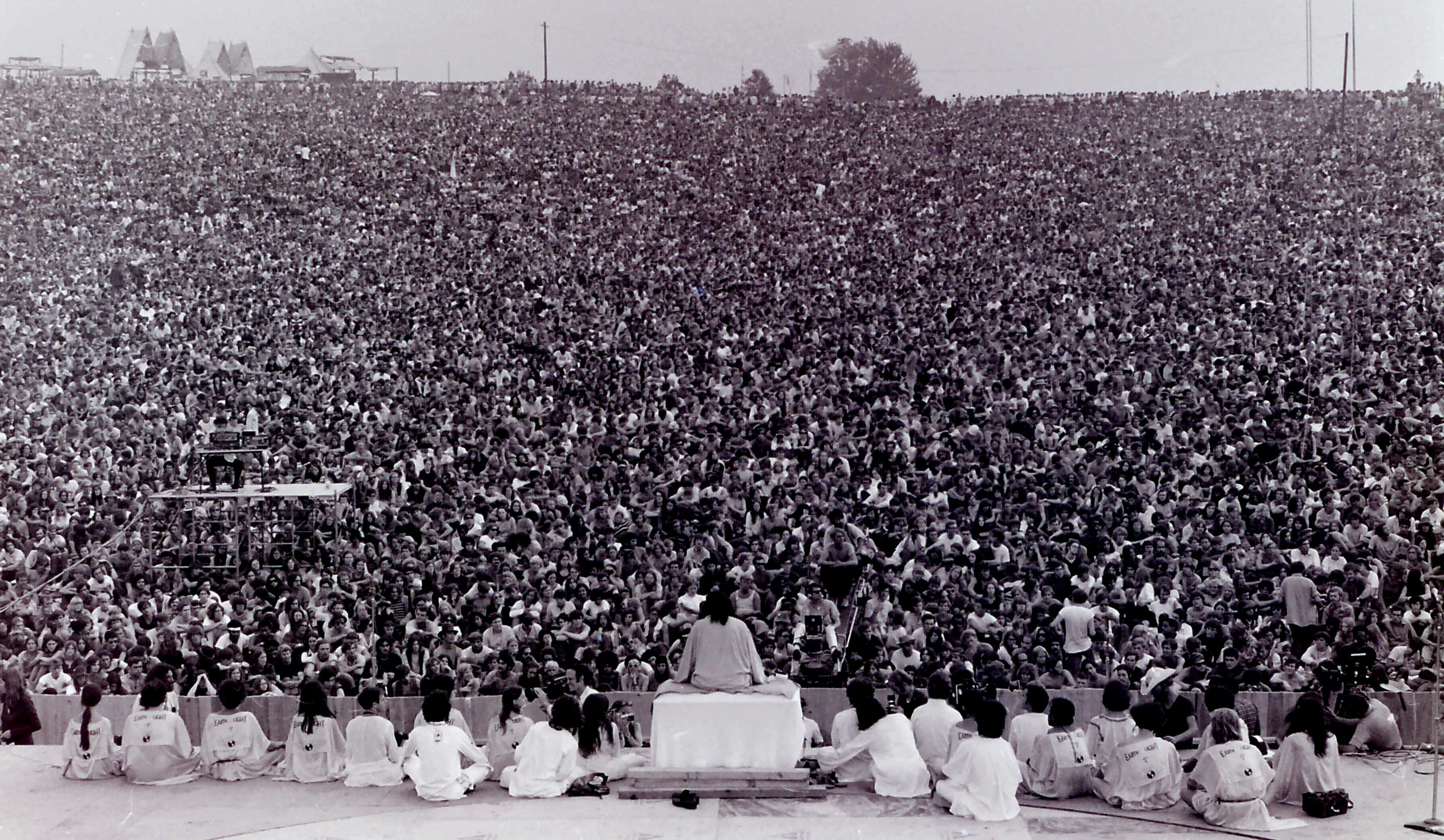

Cultural historian Grace Hale, Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History, said Woodstock and Altamont had a outsized impact on the culture because they were mass events (an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 attended Woodstock and 300,000 were at Altamont) and both were captured on film.

“They are so well-documented because there were films made that were widely seen at the time and that people can still watch today,” she said. “Those documentaries have helped cement those events in public memory.”

Michael Wadleigh’s “Woodstock” won an Academy Award in 1970 for best documentary feature. Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin made “Gimme Shelter,” a documentary on the free concert at Altamont, and captured Hunter’s death on film.

“It is pretty horrifying – it is the first film I ever saw where you saw somebody killed in the film footage,” Hale said. “Not only did that event happen at the concert, but then the fact that people could rewatch it really helped cement that sense of negativity around Altamont.”

The Maysles brothers’ film concentrates on the Rolling Stones, with only limited footage of other musicians at Altamont. It features footage from the concert and the machinations involved in setting up the show and of the documentary process itself.

“They show Mick Jagger watching the film footage, so they are showing you the process of the framing, of the setup of the very thing you are watching, which is the documentary,” Hale said. “It is a much more formally ambitious film.”

And the immediacy of the films have locked them vividly into the common consciousness.

“I do think that the reason these events resonated so powerfully for people was because of these documentary films circulating in their aftermath and allowing more people to feel they had access to the event than were there,” Hale said. “Part of the reason that so many people can claim that they were at Woodstock is that they have seen the movie. They can actually talk about it.”

The “Woodstock” film captures the feel of that festival, Hale believes, because it switches back and forth between the performances and concertgoers discussing why they are there. The focus on the music, Hale said, emphasizes it as a catalyst for social change.

“It is that coming together of the folk music revival and people who have come out of that, like Joan Baez and Arlo Guthrie and Country Joe, together with the revolution in rock that was going on all over the country, especially in California,” Hale said. “The music is amazing, and I think that revisiting Woodstock and Altamont can make people think about the relationship between music and culture and political and social change.”

These two events have come to take on more cultural weight than they can or should carry, she said.

“They have come to symbolize the high point of this flowering of the youth culture in the 1960s and then, not so long after the high point, the end – the problems that were inherent in that counterculture, the reason that those kinds of dreams of a new utopia aren’t going to come to fruition,” Hale said. “I don’t think those events, in and of themselves, are those things. It’s not quite as simple as one event being a high point and one other event being the turning point when the backlash begins to occur, but I think they are important events because they are remembered that way.”

While some in the counterculture had a simplistic approach and exhibited a naivete easily dismissed today, Hale said mass events such as music festivals could still have positive impacts on people.

“If you do want to change society, it takes a little more work than just going to an event, but I think music is a powerful force for giving people an experience outside themselves, making them feel connected to each other,” Hale said. “There is a way that music can do that so powerfully, and put people in a space where they might be ready to think about something in a different way or think about their connections to other people that they previously had not thought about. There is something wonderful about the way that music can open people up to that kind of collective experience.”

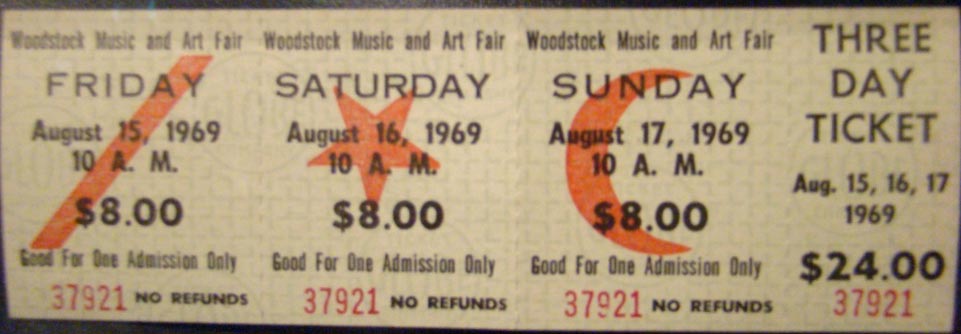

But while the documentaries captured the events, as time passes connection to the concerts fades, leaving little interest in staging a 50th-anniversary show. It becomes too hard and too expensive for aging Baby Boomers to attend a restaging of a Woodstock, Hale said, and the young don’t have the emotional connection to it.

“I think it is too far past,” Hale said. “I think it says something about how young people today don’t want to relive some other generation’s past. They want to create their own events and have their own future. I think this generation has its own rituals, its own events. … There is so much emphasis on everyone having their own particularity and individuality and difference that there is not nearly the sense in popular culture … of these great commonalities. It’s all about finding your particular niche. There is not as much interest in a mass event in that kind of world.”

Woodstock became famous in part because it was a monumental failure of logistics and Hale notes that those basic logistics would make staging another Woodstock nearly impossible.

“It is hard to imagine anywhere in the U.S. where the kids would get away with it,” Hale said “The poor organization on the one hand, and on the other, the success where everyone just shows up and then piles in. The event itself was financially a loser. If they didn’t make the money selling off the memory of it, they wouldn’t have made much money. But it is hard to imagine people being able to have something like that and it not being shut down by the police.”

Security is also much more of a concern today than it was in 1969.

“People are afraid of mass events today, with the kind of gun violence that occurs in our society,” Hale said. “You have to have organization and security if you want anybody to come at all because people are afraid of mass shootings.”

Even absent logistical concerns, shifts in the cultural landscape have blunted the impetus for a Woodstock-style event, Hale said. In a world of instant communication and niche internet radio that enables music to be quickly commodified and capitalized and sold, staging events to draw mass audiences becomes more difficult.

“One of the things that was so powerful for young people in the 1950s and 1960s is that they have a sense of themselves as an audience that matters,” Hale said. “Companies were making stuff for them, selling things to them and they have a sense of being an audience, a collective audience. That has to be exhilarating to be thought of as an audience that matters, whose taste matters. People care what you want.

“I think now we really don’t have that sense of a broad collective audience. What I think has really changed in so many profound ways is how the culture industry works, how the content is delivered to people, how people consume culture,” she said.

By the time we got to Woodstock

We were half a million strong

And everywhere there was song and celebration

And I dreamed I saw the bombers

Riding shotgun in the sky

And they were turning into butterflies

Above our nation

- Joni Mitchell

“Woodstock”