Pulling all-nighters reading your notes and textbooks might seem like the best way to cram for an exam. It’s not.

Trying to write down everything your professor says during a lecture? Also wrong.

You’re probably reading your textbooks wrong, too.

Not to worry. Help is here.

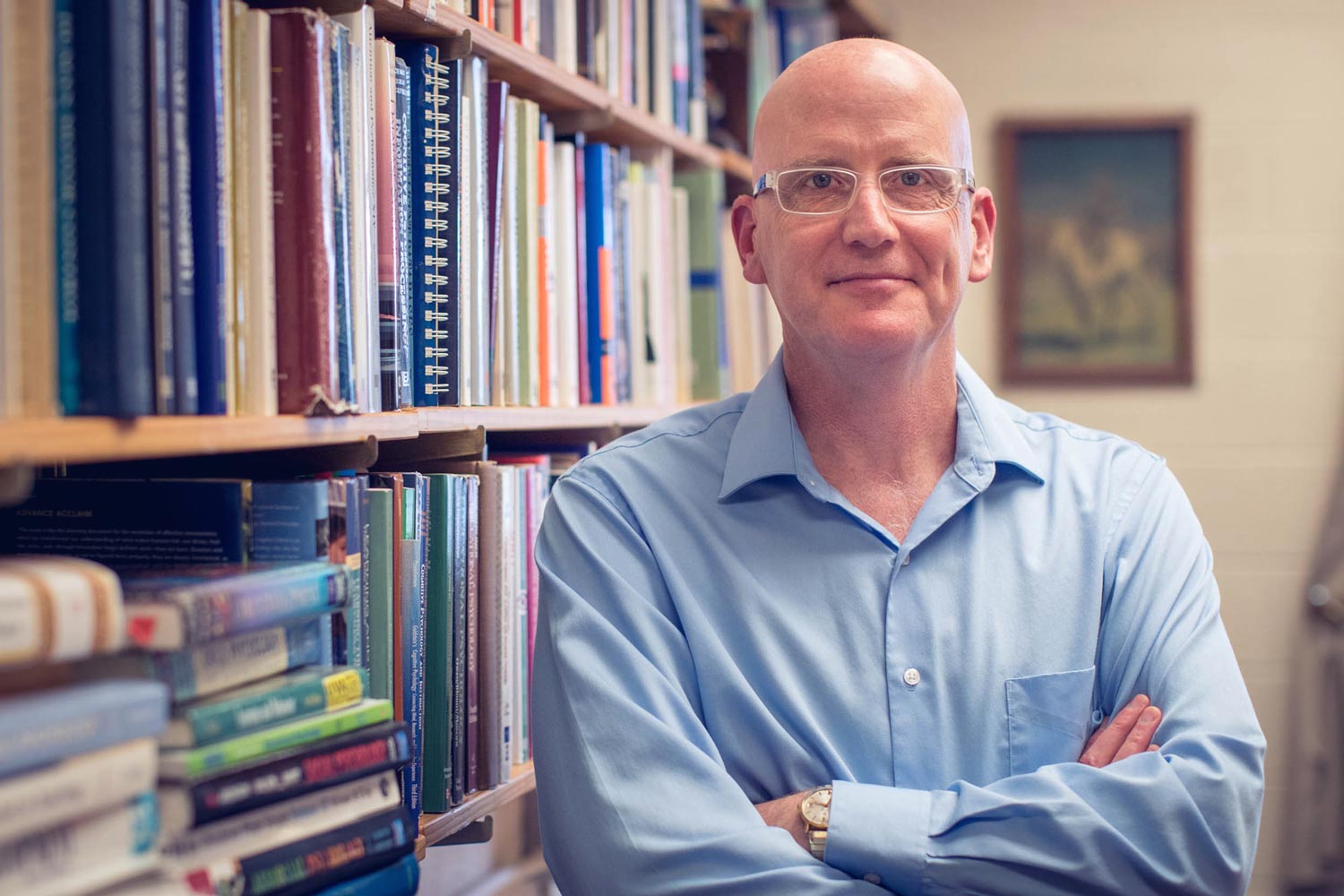

In his new book, “Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning Is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy,” University of Virginia psychology professor Daniel Willingham distills complex cognitive psychology into easy-to-digest tips and tricks to make learning, as the title of the book says, easy.

In the introduction, Willingham lays out the disappointing status quo for most students, starting in their early teens.

The class format of school-based lectures followed by note and textbook studies at home for tests makes some awful assumptions about students.

One, that they know how to set priorities and schedules.

Two, that they can read content independently.

Three, that students know how to avoid procrastination.

Four, that they can memorize content.

The list goes on.

Willingham, whom Education Week recently ranked as the country’s 10th-most influential education scholar, points out that “your brain doesn’t come with a user’s manual. Independent learning calls for many separate skills, and you needed someone to teach you. Mostly likely, no one did.”

So comes his new book, which hits stores Jan. 24 and can be preordered now. (It is already Amazon’s No. 1 bestselling new release in educational psychology.)

“How to Outsmart Your Brain” is organized in 14 easy-to-read chapters. As a recent book reviewer in Forbes Magazine points out, “While many of the chapters complement each other, you need not read them in order, nor do you need to read them all. Each one addresses its particular focus independently, allowing the reader to move directly to their biggest personal concern.”

During a recent chat with Willingham, he broke down some of the separate skills that can turn a student’s study game on its head to rewire brains for better learning.

How To Take Lecture Notes

Willingham says most people default to trying to write down everything a teacher or professor says because it feels easy and like it’s working. But people talk fast and after awhile, the notetaker is more focused on trying to write quickly and a lot less focused on understanding what they are writing. “The right strategy is to make sure you actually understand what’s going on and then take notes based on that understanding, rather than trying to write down everything that the instructor says,” Willingham said.

How To Study for Exams

Willingham says reading over notes and textbooks is the No. 1 strategy students use to prepare for exams. “It’s not very mentally taxing, but it feels like it’s effective because what you’re doing is you’re boosting familiarity,” he said. “But familiarity is not the type of memory that you need in a classroom situation.”

You need to study in a way that’s going to be closer to the way your memory is going to be called on during a test.

“You create questions as well as the answers, and then you pose the questions to yourself and answer them,” Willingham said. “This is not an obvious strategy to memorize things. It’s something students do to test whether or not they’re ready for an exam, but they don’t do it as a method of studying.”

How To Take Tests

“Part of taking tests is that a lot of students, I think, think of memory as automatic in a way, or the process of getting something out of memory as just being automatic,” he said. “In other words, if I try to remember something and I fail, it’s kind of game over. That means I didn’t learn it. And that’s not really true.”

Even as you are taking a test, there are easy things students can do to coax information out of memory. Memories tend to be organized by themes. In the book, Willingham gives an essay question as an example. “Suppose I ask you to name as many animals as you can in 30 seconds,” he said. At first, most people are very, very fast, but tend to run out of gas. As a nudge, “Suppose I then say, ‘Do I know any Australian animals?’” Willingham prods. “Oh my gosh,” comes the response. “I could have said kangaroo. I could have said wallaby.

“Because memory is organized in themes, this is something you can actually use on an exam if you are asked to write an essay about what happened in France after World War I,” he said. In that case, the themes might become social, political, economic, and so on.

The standard advice when beginning to take a test is worth following, too, Willingham said. Spend 30 seconds reading the instructions of the exam and skim the test to get a sense of how much time you can spend on each question.

If test anxiety is a problem, as it is for many, there are lots of things students can do, like reducing caffeine intake, pulling on a hoodie if isolation is helpful and even wearing dark glasses.

How To Read Difficult Books

“What people do when they’re reading is they pick up a textbook or a book for a class and they start reading it the way they would read anything else,” Willingham explained. “They start reading it the way they would read light fiction or light nonfiction that they would read for pleasure.”

The trouble with that approach is books that you read for a class are structured differently. When it’s a novel, there is a narrative. But with textbooks, there are chapters that are usually organized hierarchically.

“You’re also reading it for a different purpose. You’re not reading it for pleasure. You’re reading it because you’re trying to understand unfamiliar content,” Willingham pointed out. And the odds that you’re going to understand it well the first go-round are not good.

And then you start highlighting stuff.

“When you’re highlighting it, you think that you’re highlighting the most important ideas, but you’re probably not doing that great of job of it because it’s your first time through on these new, unfamiliar, difficult ideas,” Willingham said. In fact, studies show that when students highlight things, they are not usually the things an expert would suggest.

The thing to do is orient yourself to what you are reading and understand, going in, what your goal is. Perhaps you are reading a chapter about the evolution of the mammalian brain. Before digging in, flip through the pages to get a sense of the information that will presented in your assigned reading.

Then the reader can start posing some questions to themselves. “The idea is, ‘By the time I finish reading this, what do I think I will have learned?’” Willingham said.

One question may be, “What are the differences between the brains of humans versus the brains of primates?”

“And then you do your reading and you have these questions in mind,” Willingham said. “You’re looking to see, ‘Did I ask good questions?’ If so, great. ‘What are the answers?’”

If the answer is “no,” now is the time to perhaps do another scan of the chapter and find better questions, which in turn, yield the right answers.

“How to Outsmart Your Brain” is rounded out with chapters on how to defeat procrastination, how to plan your work and how to cope with anxiety.

Willingham hopes to break a cycle he has seen time and again during office hours with students. They come to him after not doing well on a test and they all say the same thing: “I didn’t study enough.”

“Their solution was almost always ‘more time of the same things I’ve been doing,’” he related.

“This book has 14 chapters, and each of those 14 things has to be in place if you want to do well in school,” he said. “So when you’ve got a problem any one of those 14 [things], maybe it could be improved.”

Media Contact

University News Senior Associate Office of University Communications

jak4g@virginia.edu (434) 243-9935

Article Information

July 2, 2025