Treating Patients

Dr. Catherine Bonham, an intensive care physician on UVA Health’s COVID-19 ward, studies how the human immune system responds to viral infections. She and colleagues are examining the immune responses of COVID-19 patients, and how they differ from influenza infection.

Q. How does COVID-19 compare with the flu?

A. Death rates are higher from COVID-19 than the flu. The situation is evolving, and we won’t know the long-term outcome – the patient recovery rate from COVID-19 – until months from now. It may be that the number of people who need treatment are the tip of the iceberg in terms of total infections. I am almost certain that as we do more testing and get a better grasp on how many people have been infected, the mortality rate will go down. But that could be said of the flu as well, if we tested extensively for it.

This novel coronavirus appears to be not only highly contagious, but it also sickens a high number of people, requiring hospitalization. Even during a bad flu year, we don’t see anywhere near the number of patients coming in that we’ve seen with COVID-19. A once-in-a-lifetime infectious event like this can overwhelm hospitals. It can make mortality rates look worse because our health care system generally does not have the capacity to care for large numbers of patients getting sick all at once.

This is why social distancing is so important – it reduces the number of people getting sick all at once, putting less strain on our health care system.

Q. How are you treating patients with COVID-19?

A. We are using proven therapies. We know that the antiviral medication remdesivir will help and not harm patients, and the steroid dexamethasone helps with inflammation, so our patients are receiving those drugs when appropriate. We also are conducting clinical trials for some promising therapies.

With application of evidence-based supportive care, we can treat COVID-19 as effectively as any viral pneumonia. This includes adjusting ventilators so as not to cause injury to the lungs, optimally positioning our patients so they can best receive oxygen, smart management of intravenous fluids to avoid complications like kidney failure, and, very importantly, using a team approach to treatment where physicians, nurses and technicians employ best strategies for each patient’s care.

Q. What are your concerns as we navigate this pandemic?

A. I’m concerned as we are seeing spikes in critical cases, and I’m not sure we as a nation have the safety net needed for critical care survivors, particularly people who are uninsured or underinsured.

I’m also concerned for patients who develop pulmonary fibrosis, which is scarring of the lungs. That leads to significant disabilities requiring long-term oxygen.

But as we continue to learn, we are getting better at treating COVID-19. I’m cautiously optimistic that we will eventually have a vaccine and effective specific treatments for this disease.

Q. As more people become infected, will we develop herd immunity?

A. To develop herd immunity, about 80% of the population must become infected and immune. It’s a long and dangerous road; as many people will get severely sick and die along the way.

The challenge will be finding vaccines that give long-lasting, durable immunity. In non-novel coronavirus, immunity can last two to three years at best. With the novel coronavirus, studies indicate that immunity may start declining within several months. We will need to innovate a vaccine that provides long-lasting immunity.

Learning From the Pandemic

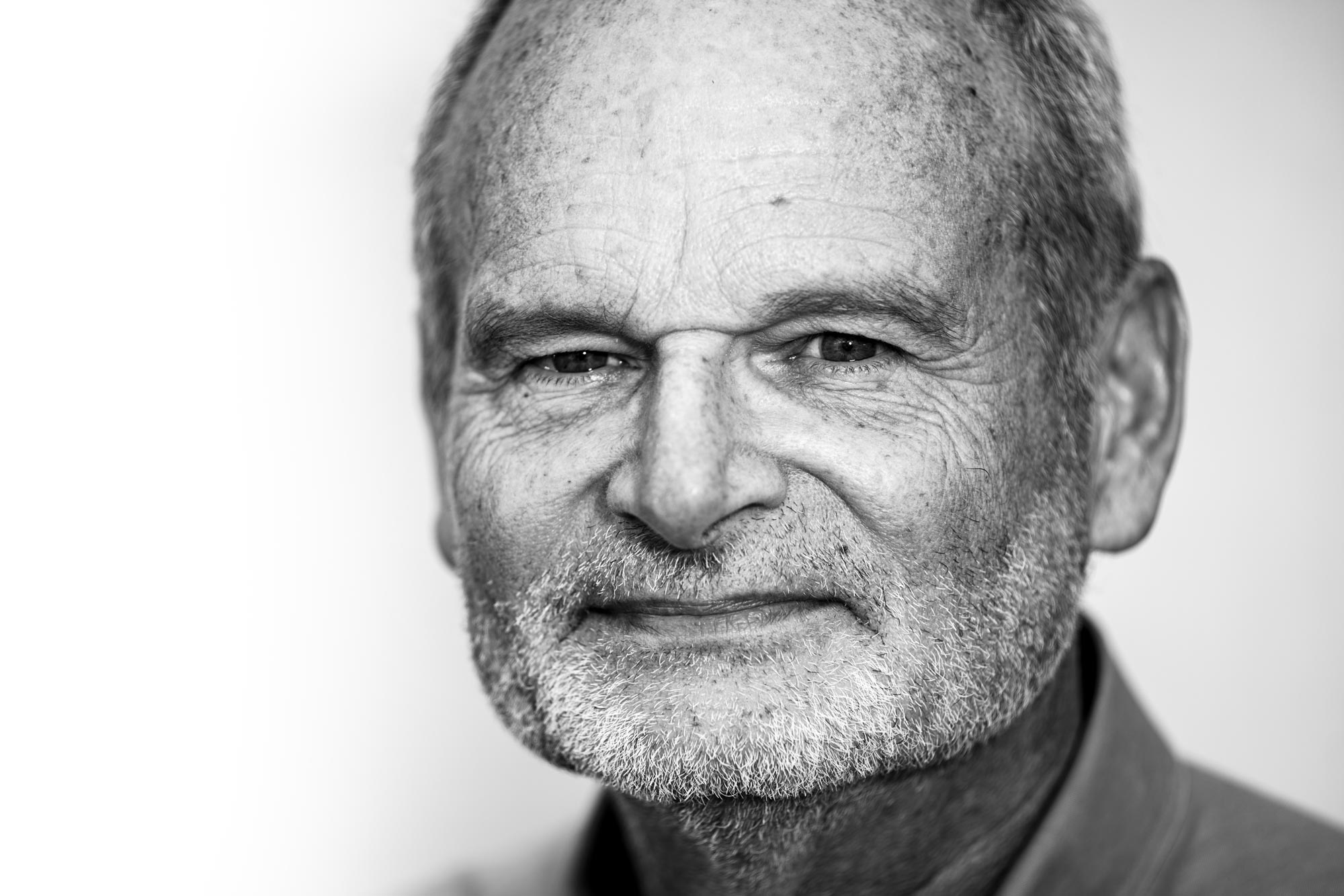

Dr. William Petri, a chaired professor of infectious diseases and international health at UVA and vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine, is studying the effects of the disease on the immune system and seeking new treatments and vaccines.

Q. Why are some people affected very little by this infection, while others crash?

A. The No. 1 risk factor of this disease is age, and that’s independent of coexisting illnesses like lung disease or heart disease. The older you are, the more vulnerable you are. If you are 80 years old, you are 100 times more likely to die than somebody who’s 50. If you are 50, you are at somewhat greater risk than a 20-year-old. Every year beyond 50 increases your susceptibility, often determining whether you end up in the hospital or can recover at home.

We don’t understand why that is. It’s possibly a difference in the way the immune system reacts to this virus as we age.

People with preexisting illnesses, such as lung disease and diabetes, are more likely to have a severe negative outcome with this disease. And, the more exposure to the virus – the more virus in your nostrils and lungs – the more likelihood of a bad outcome.

Q. What is our responsibility as individuals and as a society to bring this pandemic under control?

A. We’re all in this together. We’re responsible, and it’s a completely solvable problem. If everyone wore masks for a few weeks, we’d see a huge diminishment of infections. It’s an acute infection, and in almost everyone, the immune system does a great job of curing the infection. It’s not like HIV, where once you’re infected, you’re always infected. So, if we can stop transmission by wearing masks and maintaining some distance, this could nearly disappear in a few weeks.

Q. What have we learned from this pandemic, and are we ready for the next one?

A. There is continued risk for new pandemics. People in government and medical circles have been thinking about this for a long time and their foresight has helped us deal with this one. We’ve learned from this pandemic that you can stop international travel, and that sheltering in place works well to reduce transmission of infection. We’ve had to do that at incredible economic cost.

In vaccine science, we’re learning that there’s a certain amount of “plug-and-play” – that techniques used to develop a vaccine for one pathogen can often be applied to another. The reason we’re going to have a vaccine in 2021 is because of foresight, government funding for research, and innovations.

We will be better prepared for the next pandemic because of the lessons we’ve learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Race Disparities and COVID-19

Dr. Ebony Jade Hilton, an anesthesiologist and critical care physician at UVA Health, is deeply concerned about the high rate at which COVID-19 has swept through Black and Hispanic communities. Adjusted for age, Black people are 3.7 times more likely to have died of COVID-19 than white Americans. Latino Americans are 2.8 times more likely to have died than whites.

Early in the pandemic, Hilton pushed for state and federal health officials to release demographic data about the spread of the disease.

Q. Why are African Americans and Hispanic Americans so disproportionately affected by COVID-19?

A. Simply put, systemic racism. We cannot discuss the issue of increased morbidity and mortality amongst racial minorities without mentioning [political, social and health] inequities negatively charged toward racial minority communities: financial insecurities, housing inequities, industrialization and environmental racism, food deserts, under-resourced educational systems, and lack of health care access being a few. The overlap of these targeted systems is the perfect breeding ground for disparities to fester.

For example, take the higher infection rate. It should come as no surprise that Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to contract COVID-19 when they make up a large percentage of the employees we now collectively call “essential workers.” While the bulk of America was allowed to take refuge in the safety of their homes, racial minority groups were largely tasked with keeping the nation afloat. These individuals who have had to protest for the last several decades for a livable wage were now the frontline workers of the grocery store, farm workers and custodial staff members helping to keep hospitals and retail centers alike functional for those in need.

Just how many were put at risk? Well, studies show that only one in five Black people can work from home with the same being true for one in six Hispanics. As a double insult, many of these same workers can’t afford health insurance and often lack a primary care physician, thereby putting themselves at lesser odds of getting care when they are sick.

These same essential workers are also more likely to live in heavily populated areas and within multi-generational homes. Similarly, they often rely on public transportation. This close proximity again fosters the perfect breeding ground for the festering of COVID-19.

As is often stated, “Your zip code is a more important determinant of your health outcomes than your genetic code,” and COVID-19 unfortunately highlights this as fact for the Black and Hispanic community.

Q. COVID-19 also more severely affects people with comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension. Is this a factor as well for Black and Hispanic people?

A. Absolutely, and again it ties back to systemic racism and the impact of necropolitics [the use of social and political power to dictate how some people may live and how some must die] on the social determinants of health. We know COVID-19 kills, but so does poverty.

Take, for example, diabetes and hypertension. We cannot discuss its prevalence within racial minority communities without addressing the food deserts that exist within those communities, i.e. the lack of grocery stores or healthy eateries within walking distance of a community. These communities, on the contrary, are littered with fast food restaurants with limited areas allotted for green spaces to promote physical activity or even sidewalks, for that matter. In the long run that plays into diabetes and hypertension, heart failure, renal disease and kidney disfunction related to high sodium content.

Outside of the metabolic processes, in the era of COVID-19, we can’t discuss the mortality associated with the pre-existing disease of asthma or chronic lung dysfunction without mentioning the industrialization of poorer communities and the poor air quality that follows.

So, if you have these chronic health conditions, before COVID-19 even touches you, your body is set up to fail when stressed by the virus. It’s a perfect storm.

And it’s a vicious cycle. The climb for a child of this community to grow up to be an adult capable of affording a way out is a steep climb to make. We know this is usually accomplished through educational attainment; however, schools in minority neighborhoods are largely under-resourced. Why? Because upwards of 80% of local school funding is based on local property taxes, and if you are poor, you are less likely to own a home. So, the children of this community begin their hamster wheel race beginning in elementary school. Despite their best effort, many grow up to have the same type of low-paying jobs as their parents, which means less access to health insurance and quality health care, less health literacy, less preventive medicine and worse health outcomes.

Q. What can be done about this ongoing problem?

A. Every disease process and contributing factor can be traced back to a policy that fails the targeted group of people. If we want to better the outcome, we must first acknowledge and then address the disease of systemic racism. These issues need to become important to everyone, not just the racial minority groups. Americans in totality need to say that what we are doing is wrong; that we need to take better care of our citizens.

I am a fatal optimist. I hope that my work and message will touch people who don’t look like me, in a way that will make them want to pick up the torch and say, “How can I look at these systemic problems and make a difference in my own way for other people?”

We are going to be dealing with this pandemic for a while. Unfortunately, a lot of Black and Hispanic people will die before we get a vaccine. But I’m hoping that the impact of this situation, which affects all of us – including people of wealth – will force the nation to address the fundamental flaws at the heart of our ongoing and severe health disparities. It’s time to fix this two-tiered health system that often times falls along the lines of race but is rarely mentioned and definitely too often left unaddressed.

Seeking Treatments

Peter Kasson, a professor of molecular physiology and biological physics, is conducting research into the feasibility of using purified antibodies from convalescing COVID-19 patients for treating patients who are at heightened risk of getting extremely ill from the disease. He also is studying the use of antiviral medications for specifically treating COVID-19.

Q. How are we doing as a nation in responding to this pandemic, and are we prepared for another one?

A. One of the great strengths of the U.S. is our exceptional biomedical research enterprise. We really have reoriented well to tackle the COVID-19 challenge, and we’re making a lot of progress on several fronts. What we’re learning and doing, in terms of vaccine development and innovative treatments, will prove incredibly useful in the long run, but it does take time to make all of this happen. We’re in a race to ramp up more and better testing, and to develop vaccines and therapies that will bring this pandemic under control. In the meantime, the public health measures that everyone is taking to reduce infectious spread are critical.

The key question for the future is, do we have sufficient will and initiative to continue to implement what we’ve learned from this pandemic? Pandemic preparedness must become a top priority for our government when assessing the many security threats facing the nation.