__________________________

Notes

1. The present-day University of Virginia Medical Center was called “The University of Virginia Hospital” or “UVA Hospital” during much of the 20th century. This name will be used throughout this article when referring to the UVA Medical Center. Letter from T.J. Sellers, Reverend E. Loyd Jemison and Douglas Edwards to J.L. Newcomb. Jan. 24, 1943. Papers of the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/2.541 Subseries I Box: 7 Folder: Medical Department—Hospital 1943-1944. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

2. Lentz, C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 18, 1943. Annual Reports to the President, 1942-1943. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

3. Letter from T.J. Sellers, Reverend E. Loyd Jemison, and Douglas Edwards to J.L. Newcomb. Jan. 24, 1943. Papers of the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/2.541 Subseries I Box: 7 Folder:Medical Department—Hospital 1943-1944. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

4. Ibid.

5. Letter from J.L. Newcomb to T.J. Sellers. Feb. 2, 1943. Papers of the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/2.541 Subseries I. Box: 7 Folder: Medical Department—Hospital, 1943-1944. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia.

6. When asked by a Hospital administrator, presumably Lentz, whether they would take over dishwashing from volunteer canteen workers, Mrs. Clemons of the Hospital Circle said that “she wished it clearly understood that the organization did not do this, as the case was definitely a labor situation.” Minute Book of the Regular Meetings of the University of Virginia Hospital Circle, September 1940-June 1945. The University of Virginia Hospital Auxiliary Collection, 1908-2014. MS-13. Box: 1 Folder: 4 Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

7. Lentz, C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, May 4, 1944. Annual Reports of the President. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

8. Barringer, P.B. (1900). The Sacrifice of a Race. Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards Broughton, Printers and Binders. p.28.

9. Moll. W. and Savitt, T.L. (September, 1975). The Early Years of the University of Virginia Hospital: An Analysis of Patients’ Records. Virginia Medical Monthly. Volume 102. p. 718.

10. This division of labor is apparent in a personnel report the University of Virginia submitted to the Governor of Virginia in 1937. In the report the term “Negro worker” is used interchangeable with the job titles of “Hospital Orderly” and “Ward Maid”. [Personnel Report to the Governor]. Circa April 7, 1937. Papers of the President, 1937-1938. RG-2/1/2.491 Subseries III Box: 12 Folder: Personnel (survey papers), 1937-1938. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

11. Lentz. C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 15, 1941. Annual Reports to the President, 1940-1941. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

12. Meeting Minutes of the Executive Committee of UVA Hospital. March 3, 1942. Hospital Executive Director’s Office Papers. MS-7. Box: 1 Folder: 27. Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

13. Ibid.

14. Letter from T.J. Sellers, Reverend E. Loyd Jemison, and Douglas Edwards to J.L. Newcomb. Jan. 24, 1943. Papers of the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/2.541 Subseries I Box: 7 Folder--Medical Department—Hospital 1943-1944. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

15. Lentz, C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, May 4, 1944. Annual Reports to the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

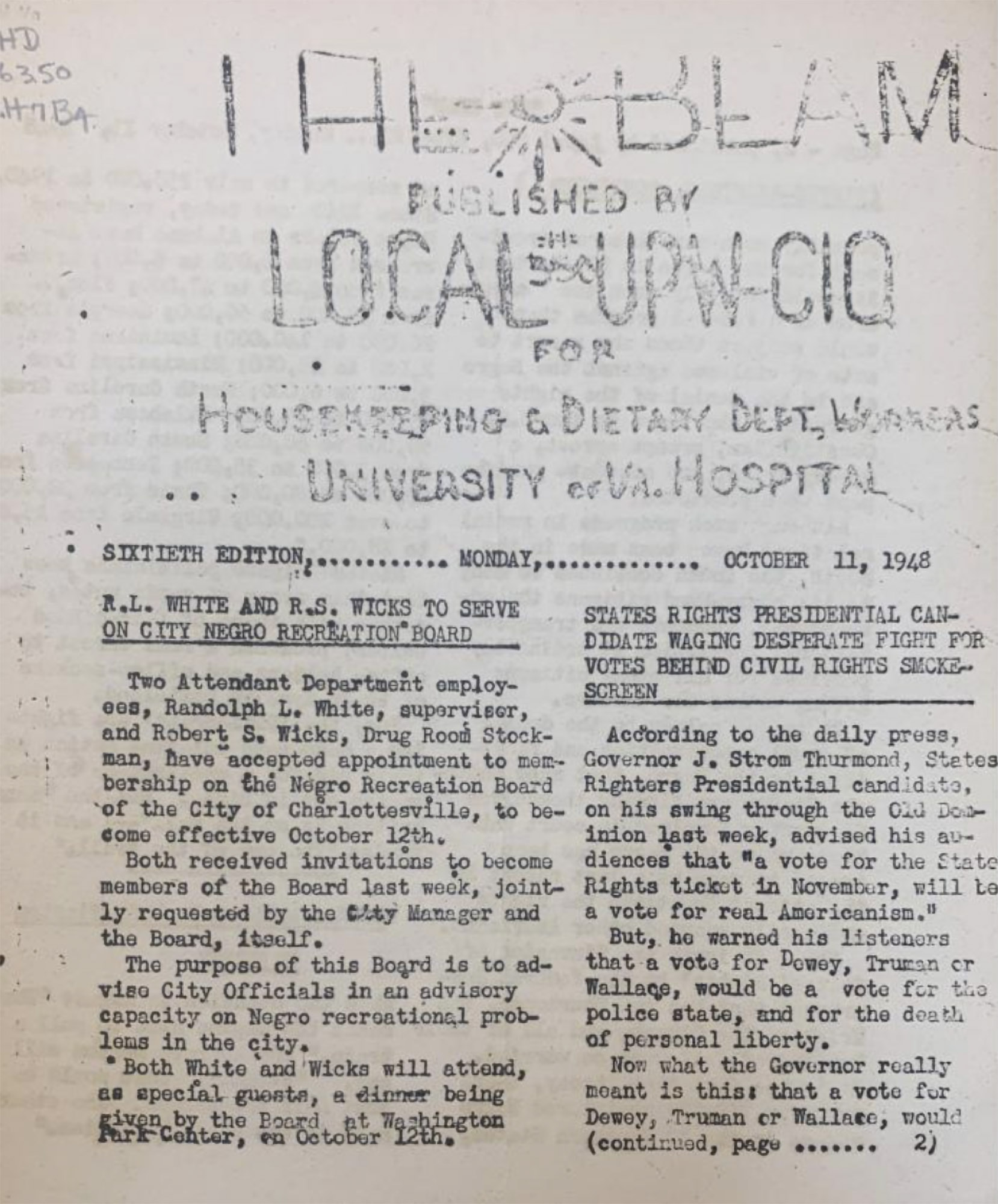

16. In later years, Local 550 changed its affiliation from SCMWA-CIO to United Public Workers-CIO (UPW-CIO).

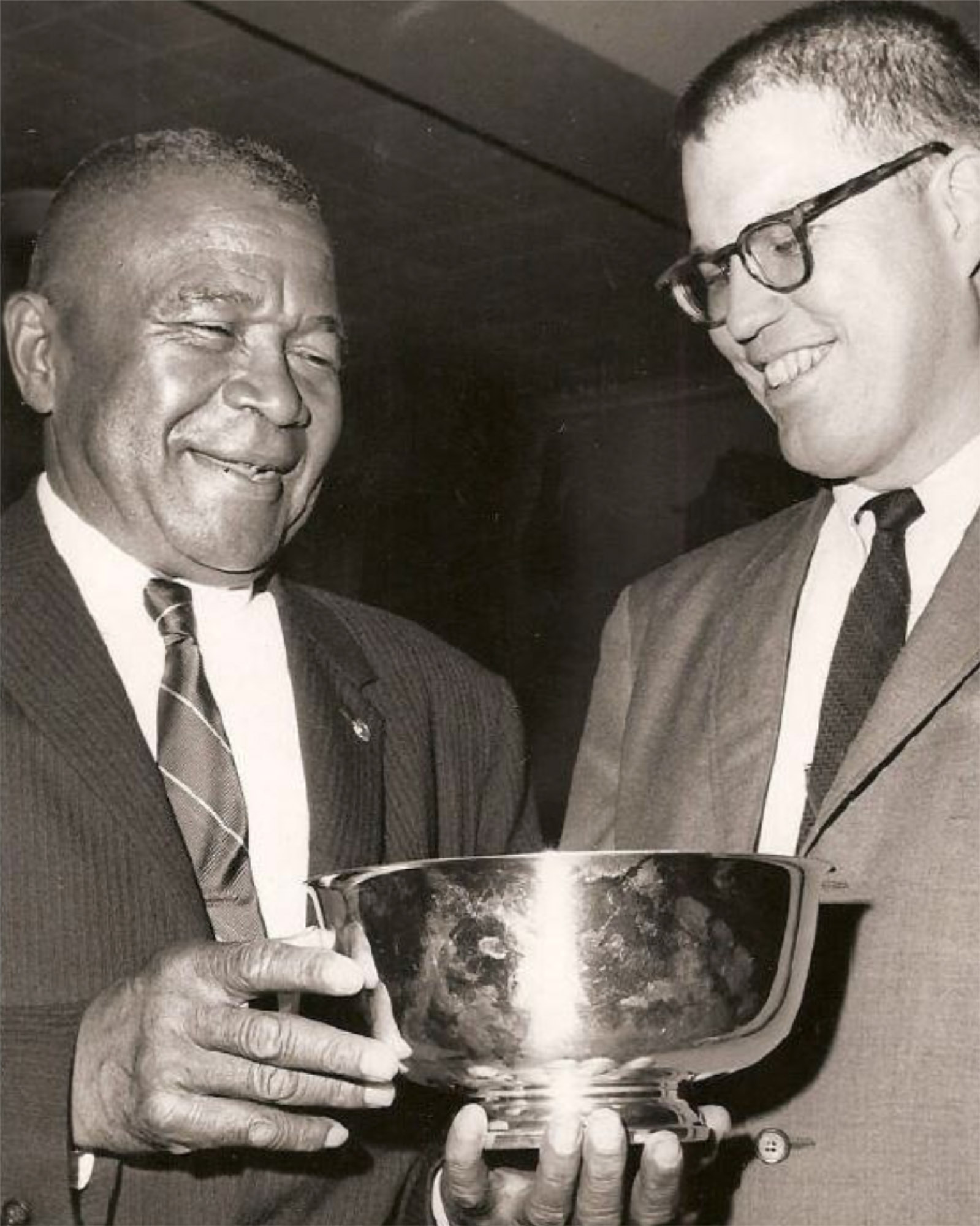

17. “Local 550 Launches Intensive Drive for New Members, New Votes.” Dec. 6, 1948. The Beam. Published by Local 550 United Public Workers-CIO.

18. Maurer, D. “Yesteryears: Randolph White.” Daily Progress. July 29, 2014.

19. Ibid.

20. Lentz, C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 18, 1937. Annual Reports to the President, 1936-1937. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

21. Maurer, D. “Yesteryears: Randolph White.” Daily Progress. July 29, 2014.

22. Sullivan, P. (1996). Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. p. 83.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Lentz, C.S. Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, May 4, 1944. Annual Reports to the President, 1943-1944. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

26. Lentz, C.S. Biennium Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 16, 1946. Annual Reports of the President, 1945-1946. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

27. Letter from J.L. Newcomb to Abram P. Staples. March 12, 1945. Papers of the President 1943-1945. RG-2/1/2.541 Box: 18 Folder: Medical Department--Hospital. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

28. Superintendent Lentz reported that in the spring of 1945 the Attorney General prohibited him from engaging in collective bargaining with the Union. Lentz, C.S. Biennium Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 16, 1946. Annual Reports to the President 1945-1946. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

29. Lentz, C.S. Biennium Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 16, 1946. Annual Reports to the President 1945-1946. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

30. Letter from Ernest B. Pugh to J.L. Newcomb. May 3, 1945. Papers of the President, 1943-1945. RG-2/1/2.541. Box: 18 Folder: Medical Department–Hospital, 1945.

31. Lentz, C.S. Biennium Report of the UVA Hospital Superintendent, Jan. 16, 1946. Annual Reports to the President 1945-1946. RG-2/1/1.381. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

32. Virginia-General Assembly, Regular Session: 985-1056 1946. Senate Joint Resolution No. 12 Unionization of Officers and Employees of the Commonwealth Agreed to Feb. 8, 1946.

33. “Local 550 Launches Intensive Drive for New Members, New Voters.” The Beam. Dec. 6, 1948. Published by Local 550 United Public Workers-CIO.

34. Ibid.

35. “Sisters Gussie P. Harris and Lucile Blakey, Appointed Hospital Aides A Precedent.” The Beam. July 19, 1948. Published by Local 550 United Public Workers-CIO.

36. “U.Va. Hospital Employs Negro Registered Nurses: Trains Negro Girls for Practical Nursing.” Roanoke Tribune, XI:28. Aug. 9, 1952.

37. There were 255 regularly employed Black men and women in UVA Hospital’s Housekeeping, Attendant, Dietary, and Housekeeping Departments. “210 U.Va. Hospital Negro Employees win Job Reclassifications, Salary Boosts, Retroactive to July 1, 1948.” The Beam. Aug. 30, 1948. Published by Local 550 United Public Workers-CIO.

38. “Report of an Investigation of Compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act on the Part of the University of Virginia Hospital.” April 30, 1965. Papers of the President, 1964-1965. RG-2/1/2.681 Box: 25 Folder: Medical Center-Hospital 1964-1965. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

39. “Report on the Racial Composition of the Housekeeping Department.” Nov. 3, 1967. Hospital Executive Director’s Office Papers. MS-7. Box: 21 Folder: 18. Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

40. Letter from John M. Stacey to Reverend R.A. Johnson. Sept. 24, 1963. Papers of the President, 1963-1964. RG-2/1/2.671. Box: 24 Folder: Medical Center-Hospital-General, 1963-1964. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

41. Ibid.