The history of student writing at the University of Virginia goes back to the arrival of the first class on Grounds in 1825.

From the beginning, students showed concern for robust inquiry and intellectual rigor in their formal academic writing. They often wrote about the most urgent issues of the day.

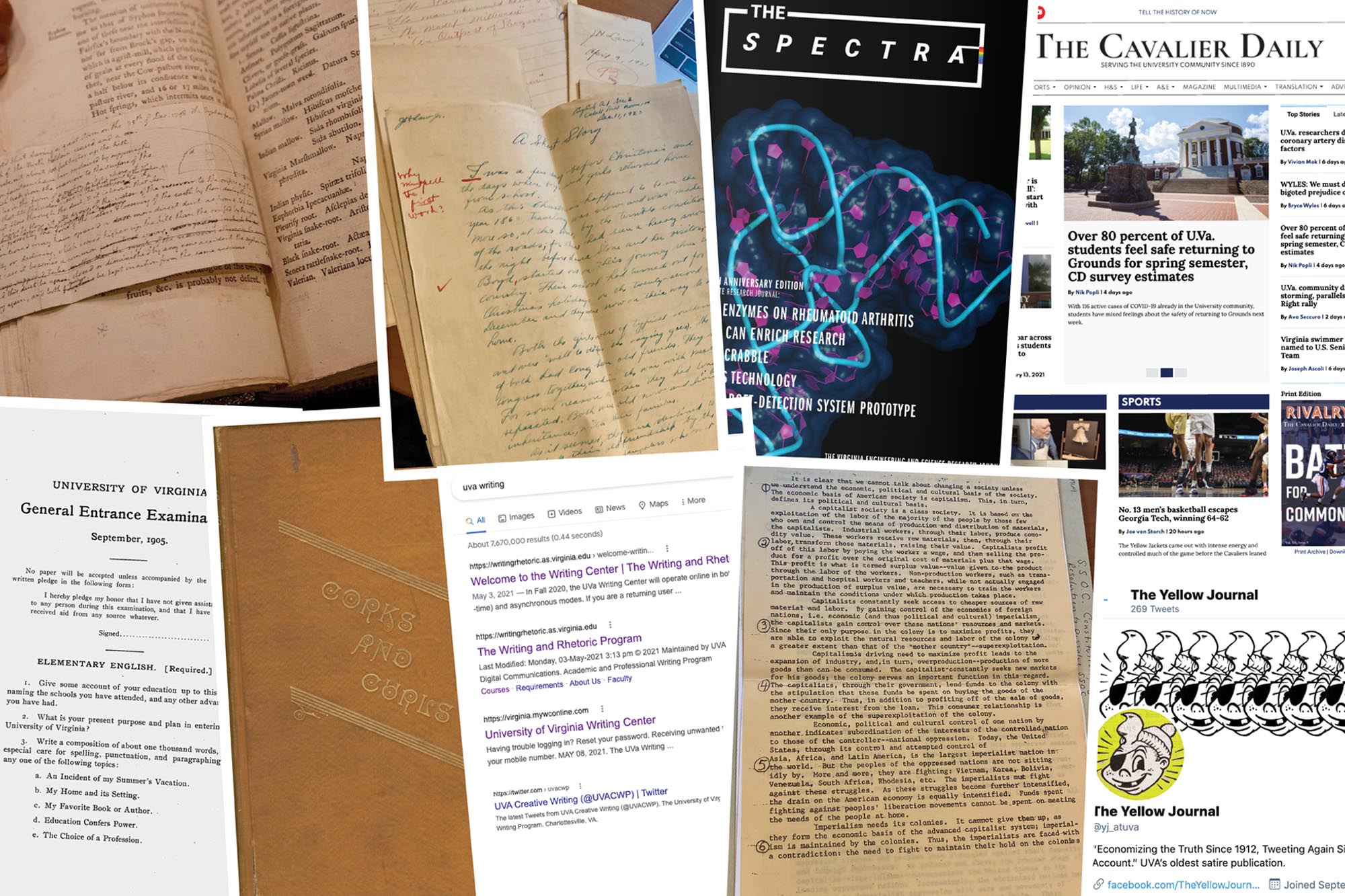

In those early days and decades, however, students also wrote in dog-eared journals, adding doodles and notes about the weather; they penned letters home asking for money, and collected pictures for scrapbooks; they typed documents and copied drink recipes from secret societies.

Stashed in folders and boxes in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library are also student papers from the 1930s making the case for eugenics and the genetic superiority of wealthy, elite white families, followed by student papers from the 1960s to the ’80s on war protests and advocating for Black student well-being. Women wrote to each other about their new roles when they were first admitted and wrote essays on how they were treated.

Media, technology and creativity have produced new ways for today’s students to communicate, from old-school forms such as painting messages on Beta Bridge to using online channels and social media apps like Instagram.

A new course this spring considered all these kinds of writing – the first course devoted to the “History & Culture of Writing at UVA,” said Heidi Nobles, assistant professor of English, at least as far as she can tell.

Students both researched and contributed to the culture of writing at UVA by analyzing mostly unpublished writing of past students and faculty members – “to see where we’ve come from,” Nobles said. In the present, they conducted surveys and interviews to investigate current writing activities across Grounds, and they created their own original writing – letters to future readers; poetry and short stories – to add to the University’s archives for future generations to read.

Following safety protocols due to the pandemic, they worked mostly in a virtual setting, but several small groups did tour the Special Collections Library with instruction librarian Krystal Appiah, and took specially arranged tours of the Grounds with University Guides.

“We are keenly aware that this university has existed for more than 200 years, and that writing has founded and guided our identity throughout all that time,” Nobles said, explaining that she created the course to enhance the culture of writing already here.

It’s part of a larger University plan to cultivate and sustain the culture of writing at UVA under the “Writing Across the Curriculum” program, which seeks to embed writing in every department and school, at every level, beyond the first-year requirement.

“We are keenly aware that this university has existed for more than 200 years, and that writing has founded and guided our identity throughout all that time,” Nobles said. (Contributed photo)

“History & Culture of Writing at UVA,” an elective course, qualifies for the second writing requirement. The seminar attracted 15 first-, second- and third-year students across different majors and a wide range of interests. It will be offered this fall for Echols Scholars, and will be open to all students in spring 2022, with enrollment capped at 16.

Throughout the subsequent courses, the students will continue to analyze writing at UVA and add their own.

“In spring 2021, our class began to investigate, ‘What IS the ‘culture of writing’ at UVA?’” Nobles said. “What has writing looked like historically here? What kinds of writing are people doing here now?”

Nobles said the students juggled conflicting feelings of pride in belonging to UVA and shock and dismay about some of its negative aspects, revealed in their studies of historical writing. The students recognized that most of them – women and racial minorities – would not likely have been admitted in previous days, she said, and they have been mature in handling the hard parts of UVA’s history.

“They’re doing their best to fulfill the spirit of the school the way it was intended,” Nobles said. “It has gone better than expected,” she said, adding, “The students have taken the idea and run with it. It’s been so rewarding.”

From her work in the course, first-year student Casey Nestor wrote, “Today’s writing culture at UVA is marked by an ardent desire to preserve our institution’s history. … I am emerging from this semester with a much greater appreciation for how writing plays an integral role in defining a culture and how impactful and permanent even my seemingly impermanent personal writing can be.”

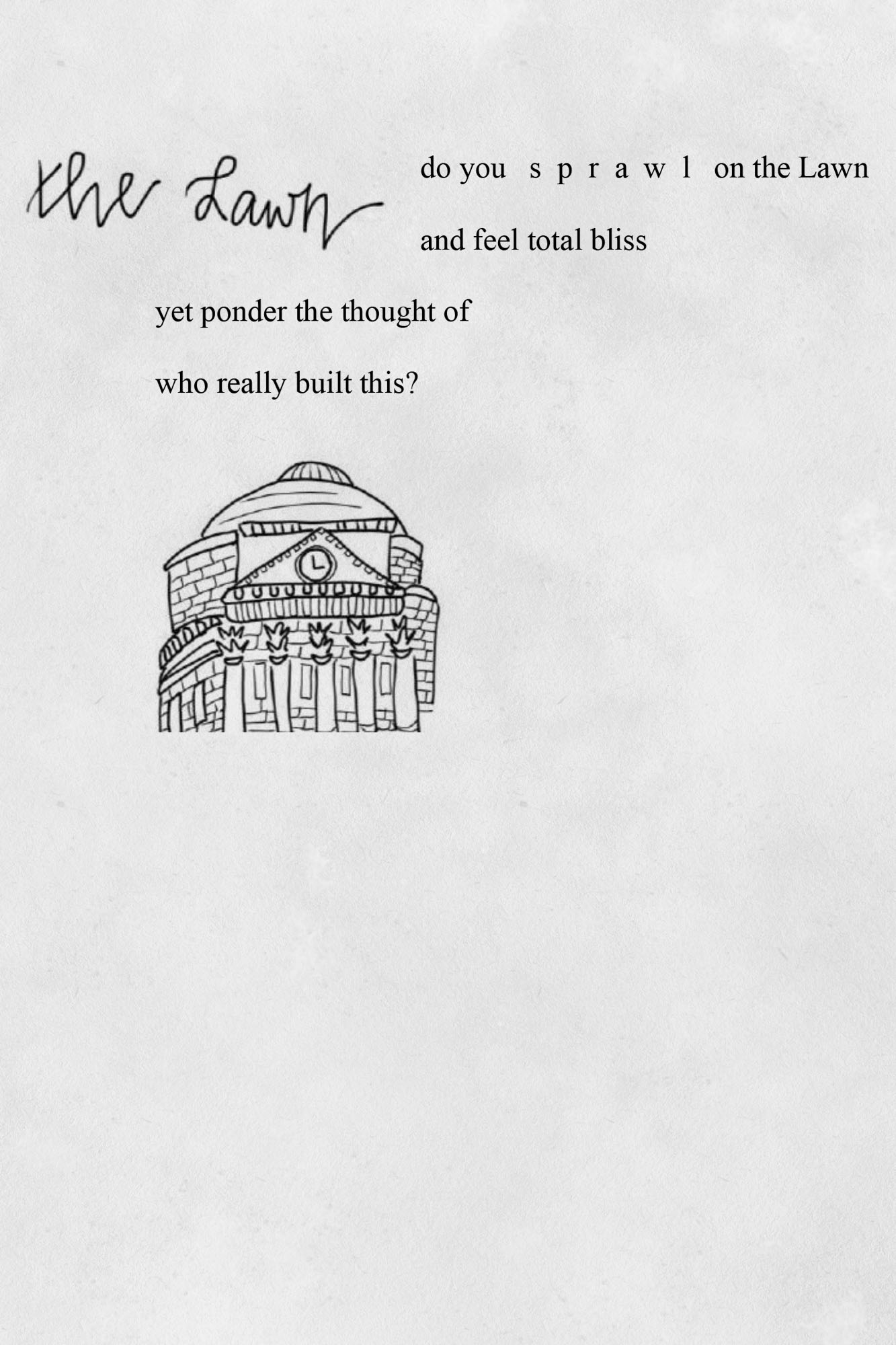

To an imagined future reader, Nestor wrote, “Reflections on joy amidst imperfection at UVA.” About her series of short verses and notes, she wrote, “These poems [are] for you, as well as for myself, to capture my experience as a UVA student and how I perceive my role as one character in our University’s greater story.”

About a short poem, “the Lawn,” she wrote, “The external beauty is overwhelming, but there is also the reality that this view would never have been possible without the toil of the enslaved laborers who built this university. My poem is formulated as a question reflecting this dichotomy that seems impossible to reconcile. I am, however, beginning to realize that maybe me loving the Lawn does not discount the moral atrocities but rather in some personal way honors those forced to construct the buildings surrounding it. I choose to love the Lawn for what it is today without forgetting the immorality woven into its history.”

Nestor said, “I recognize more fully that I was never the ideal student Jefferson imagined attending UVA, but, like so many past students, my voice as a writer and as a student still belongs here.”

Sivan Ben-David, a rising second-year student and history major from Weston, Florida, also said only because UVA has changed has she been able to find her place here as a queer woman. Getting to explore a bit in the Small Special Collections Library was especially meaningful, she wrote in an email, because she would love to work in museums someday.

“In getting to read the words of others in the UVA community, I feel like I have much greater insight into UVA as a whole,” she wrote. “I am a much stronger writer after this course, but I also feel many of my own biases have been challenged with regard to writing as a discipline.”

“Developing as a writer, in a university setting, often means developing as a researcher, a problem-solver, a thinker. This is key for future employment, yes, and this is also key for life.”

- T. Kenny Fountain

director of Writing Across the Curriculum

For one project, Nestor and Ben-David paired to compare past student writing with current writers and other professionals who wouldn’t call themselves writers. For instance, they interviewed UVA alumnus Craig Kelley, an archeologist at Monticello, and he emphasized the importance of all writing, no matter how informal, in providing insight into a find, saying he wanted to let future archeologists know even their notes could be useful.

The students conducted informal surveys and enlisted the help of UVA’s Institutional Research and Analytics office to run a formal survey of students’ experiences with writing beyond the classroom.

Nobles summarized what they found was change. In the past, student writing was more formal and constrained, or focused on a particular style; nowadays, there are more outlets for writing and modes of expression.

On one hand, the more informal writing used in social media might have expanded the breadth of topics, but given up depth; on the other hand, it’s also possible to dig deeper with a narrow focus.

Also, from having almost no formal writing from women and minority groups over the University’s history, the breadth of student expression has expanded to include the spectrum of voices participating in UVA’s ongoing writing culture.

The English department and Writing and Rhetoric program offer dozens of courses each semester to get students excited about developing their writing. As associate director of the Writing Across the Curriculum program, Nobles also works with the University’s schools, departments and programs outside of English, by helping to design a curriculum that incorporates writing as a means of improving student understanding, achievement and retention.

“There is a lot of writing going on that is not recognized as writing,” Nobles said. Student writing, however, can be enhanced with a little attention.

To that end, one major initiative, the Faculty Seminar on the Teaching of Writing, will be held online May 24-27. T. Kenny Fountain, director of Writing Across the Curriculum, is co-leading that seminar, which is designed for faculty across Grounds seeking to incorporate writing into their disciplinary courses.

“Our culture of writing seems marked by our idealism, our shared sense of responsibility beyond ourselves, and a joyous blend of dignity and raucous good humor. Yet the full story is complex …”

- Assistant Professor Heidi Nobles

“Learning to write is not like learning data. You can’t just memorize facts,” Fountain said. “It’s more like learning another language, or developing as a musician or an athlete.” Improving as a writer offers long-term benefits across a student’s life.

A 2021 report by the Association of American Colleges & Universities found that not only do employers value workers with strong writing, communication and research skills, but many employers seek out candidates whose college coursework involved significant writing assignments.

This is no surprise to Fountain: “Developing as a writer, in a university setting, often means developing as a researcher, a problem-solving, a thinker. This is key for future employment, yes, and this is also key for life. Writing-enhanced courses provide students multiple opportunities to develop in all those areas.”

As she wrapped up her first semester of teaching this course, Nobles reflected: “Our history shows our great triumphs and our undeniable moral failures. Our culture of writing seems marked by our idealism, our shared sense of responsibility beyond ourselves, and a joyous blend of dignity and raucous good humor. Yet the full story is complex, and even after months of collaborative work, we are well aware that we are working on a small piece of a large narrative. The work continues.”

Media Contact

Article Information

May 19, 2021

/content/telling-uvas-never-ending-story