Facial recognition can identify people in a crowd. Can the same be done for fish in a river with “fish-ial” recognition software?

University of Virginia data scientist Sheng Li is determined to find out.

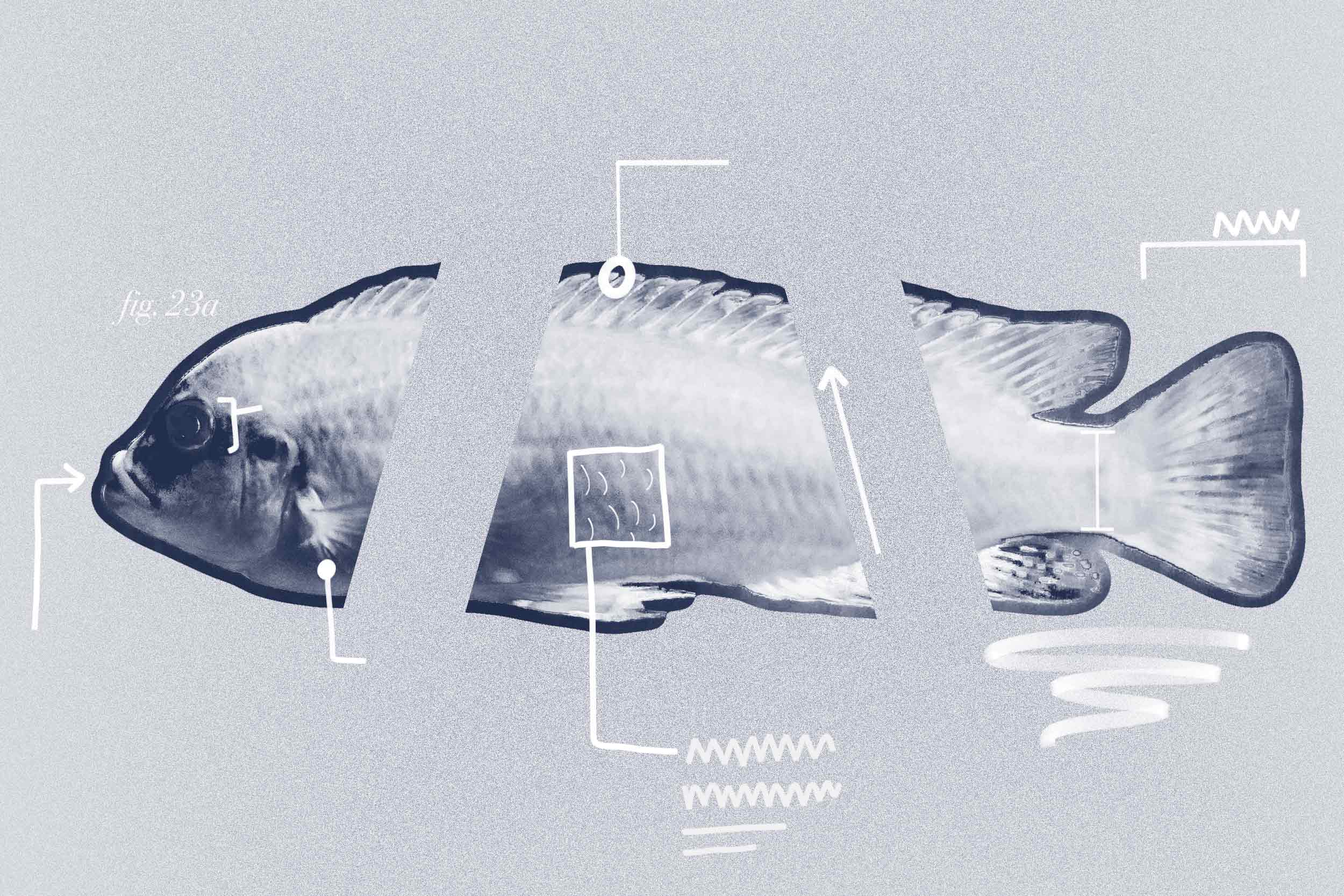

Illustration by Emily Faith Morgan, University Communications

Facial recognition can identify people in a crowd. Can the same be done for fish in a river with “fish-ial” recognition software?

University of Virginia data scientist Sheng Li is determined to find out.

In collaboration with the U.S. Geological Survey, which has provided a five-year grant, Li and his two research assistants are training a deep-learning algorithm to recognize nuances in individual fishes’ faces and scale patterns.

Sheng Li, an assistant data science professor, said it may be possible to recognize individual fish within a school by their scale patterns. (School of Data Science photo)

“It sounds impossible, but after investigating many fish images and talking to fish biologists, we realized that it might indeed be possible,” the assistant professor said.

The goal is to help fisheries and wildlife conservationists not only assess the size of fish populations in large, dynamic aquatic environments, but to track the metrics of individual specimens, with an eye toward how their health and well-being might impact the larger ecosystem.

The deep-learning project is starting with catalogues of publicly available fish imagery that will be refined over time.

New fish photos, including underwater shots, will be collected in a controlled environment by the U.S. Geological Survey researchers.

Just as with software focused on human faces, the algorithm will “look” for structures in facial topography, converting the information into data points. The program will then compare against the database of fishy faces, again and again, until differentiation begins to take hold.

Still, fish don’t have the same level of facial complexity as human do. That’s where Li hopes to put his finger on the scales – by combining information.

And in some ways, a fish’s scales are like its fingerprint.

“We all know that a fingerprint is a very reliable biometric,” he said. “The major patterns of fingerprints – i.e., loop, whorl and arch – are unique and quite stable over years. If we look at fish’s scales, they are not as ideal as fingerprints, because the pattern is simple, and the size of pigmentation might be slightly changed over time. However, even the simple patterns of scales – on brook trout, for example – still show some uniqueness that could be leveraged for fish identification.”

Li’s team is debuting its plan this month at the annual International Conference on Big Data, sponsored by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

The researchers include School of Data Science doctoral students Zhongliang Zhou and Weili Shi, as well as Nathaniel Hitt and Benjamin Letcher of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hitt, a research fish biologist, said the use of artificial intelligence may end up being preferable to the existing method of tracking fish by tagging, which is labor-intensive and physiologically stressful on the animals.

Even when the fish adapt well enough and the tags aren’t lost, only so many fish can be tracked.

“We believe this application of AI may be vital for conservation of declining fish populations,” Hitt said.

Communications Manager School of Engineering and Applied Science

williamson@virginia.edu (434) 924-1321