Being a kid isn’t as simple as it used to be. In the last 30 years, children’s lives and activities have become so much more monitored, structured and confined than they were a generation ago, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking childhood is becoming as regimented as a prison term.

Brooke Dinsmore’s research indicates that modern approaches to protect and guide kids work, but can have negative side effects on mental health. (Contributed photo)

Brooke Dinsmore, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology in the University of Virginia’s Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, researches the impact these changes are having on children’s lives and their well-being – especially their mental health. She finds that, although the increase in efforts to monitor, structure and protect the lives of children since the end of the last century have made kids healthier and safer, the benefits haven’t come without a cost.

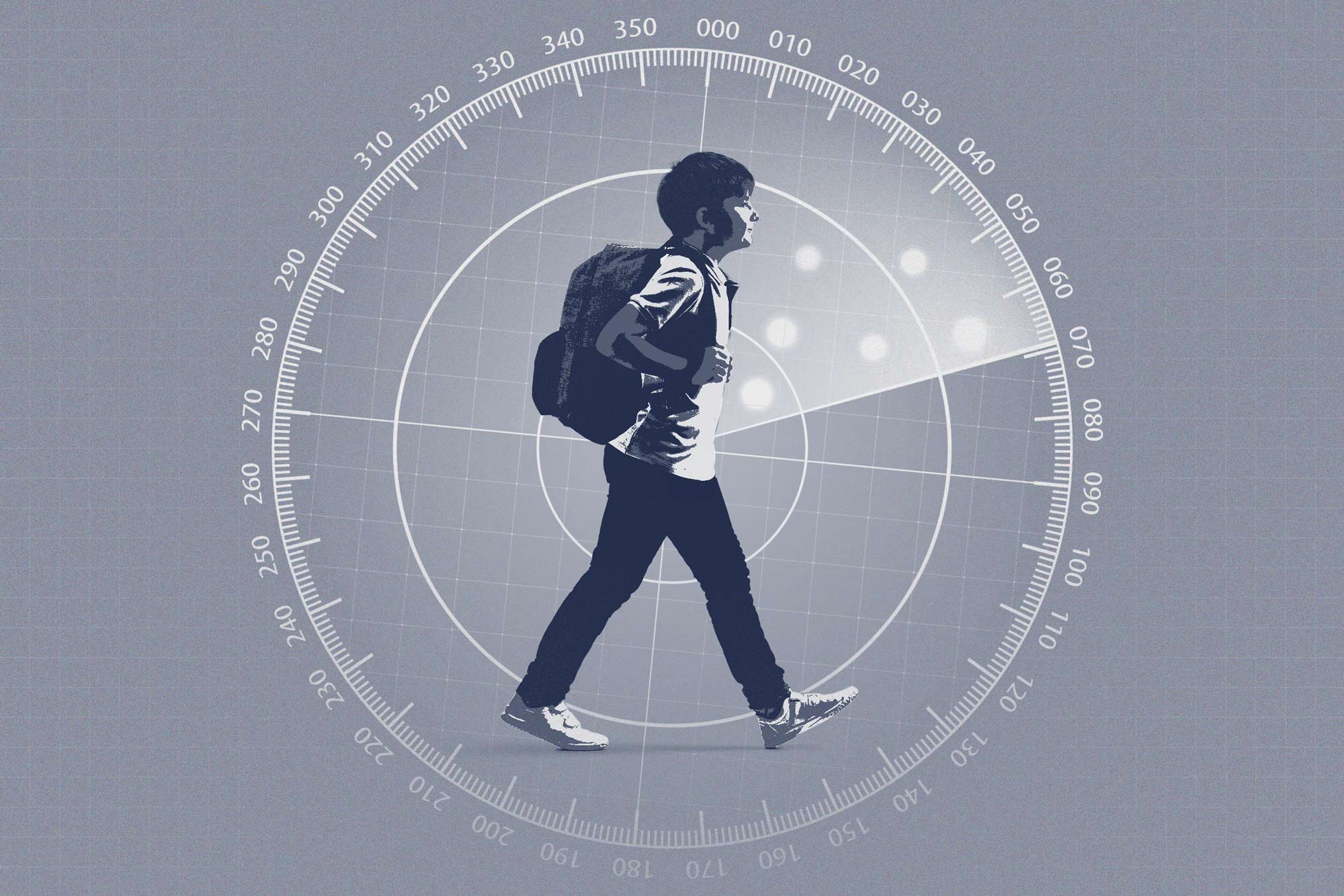

In just three decades, Dinsmore explained, children’s lives have come under increased surveillance – and not just watching, but “systematized watching,” in ways that have long been employed by the criminal justice system. Before the 1990s, it was rare to find schools equipped with metal detectors, camera systems and police officers, or school resource officers who are employed to enhance security. But few schools are without them now, a response to the modern surge of mass shootings in schools.

In addition to those physical forms of surveillance, Dinsmore explained, there has also been a drastic increase in what is known as “dataveillance,” which describes tools like standardized testing and new technology like social media that are transforming youths’ lives into data. It also includes the information that police and family services organizations are collecting on communities. And all those efforts are continuing to expand as technology makes them faster and easier to achieve.

“Youth now have a huge amount of data that’s being collected on them and on their lives, from the time they’re very young children,” Dinsmore said. “From the time their parents start taking digital photos of them.”

There’s an adjacent trend, Dinsmore explained, called “intensification,” which sociologists use to describe the increase in the expectations placed on parents to monitor their children and to structure their activities.

Children’s ability to walk to school or anywhere on their own has dramatically declined since the 1990s, Dinsmore said. Childhood has transitioned from being an activity that involved playing outside with neighborhood kids to being, especially for middle-class families, about piano lessons, karate classes and soccer leagues, which means they have far less unstructured time than they once did.

“The sum of these trends is in part a reduction of the social space of children and the independence they have in our society,” Dinsmore said.

From one perspective, according to Dinsmore’s research, high-level data suggest that the sum of these changes in the experience of childhood are leading to safer, more productive kids who are making better choices. Over the last few decades, teen pregnancies have decreased, teenage drinking and drug use are declining, achievement in school is improving and kids are doing much better on a range of health measures.

.jpg)