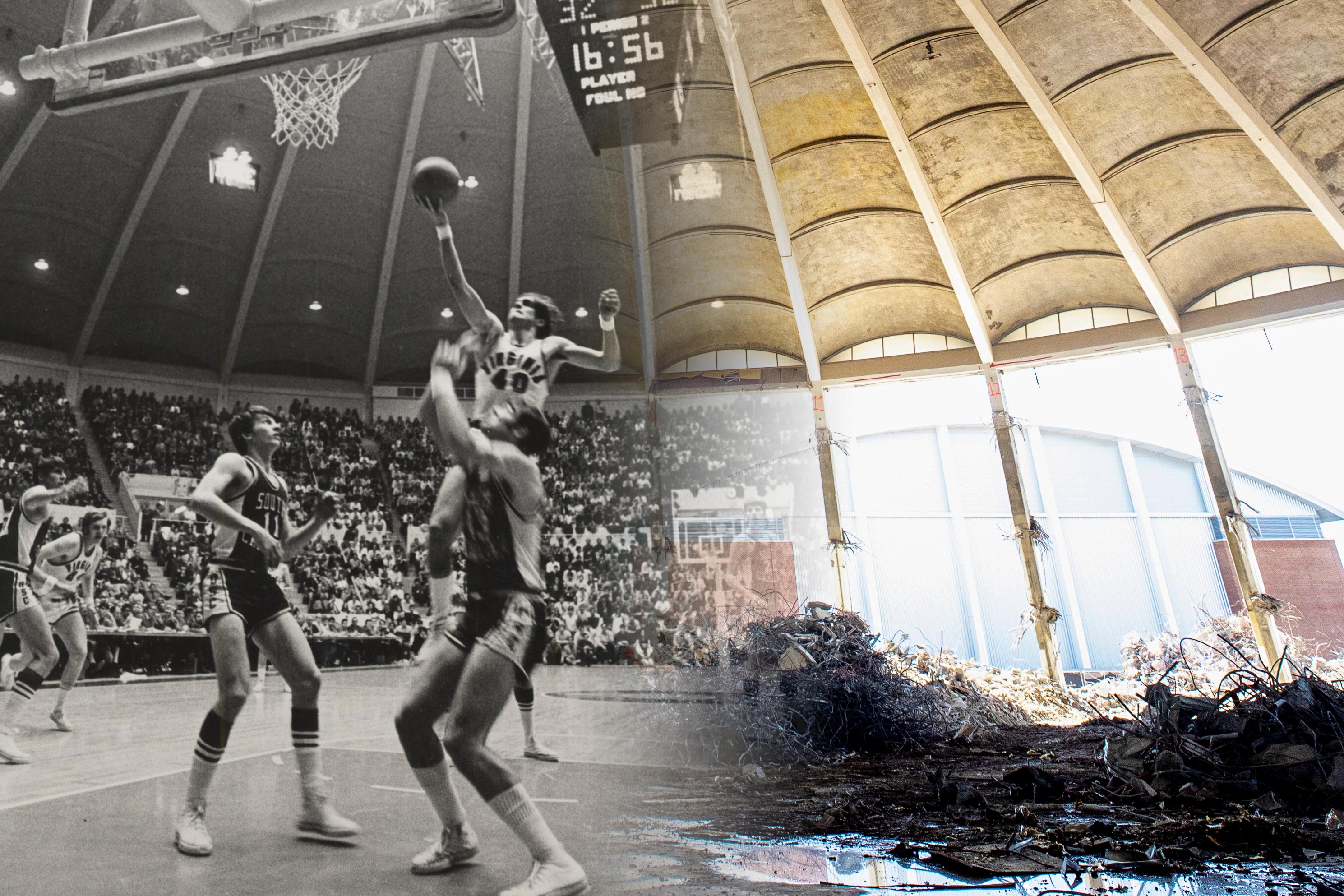

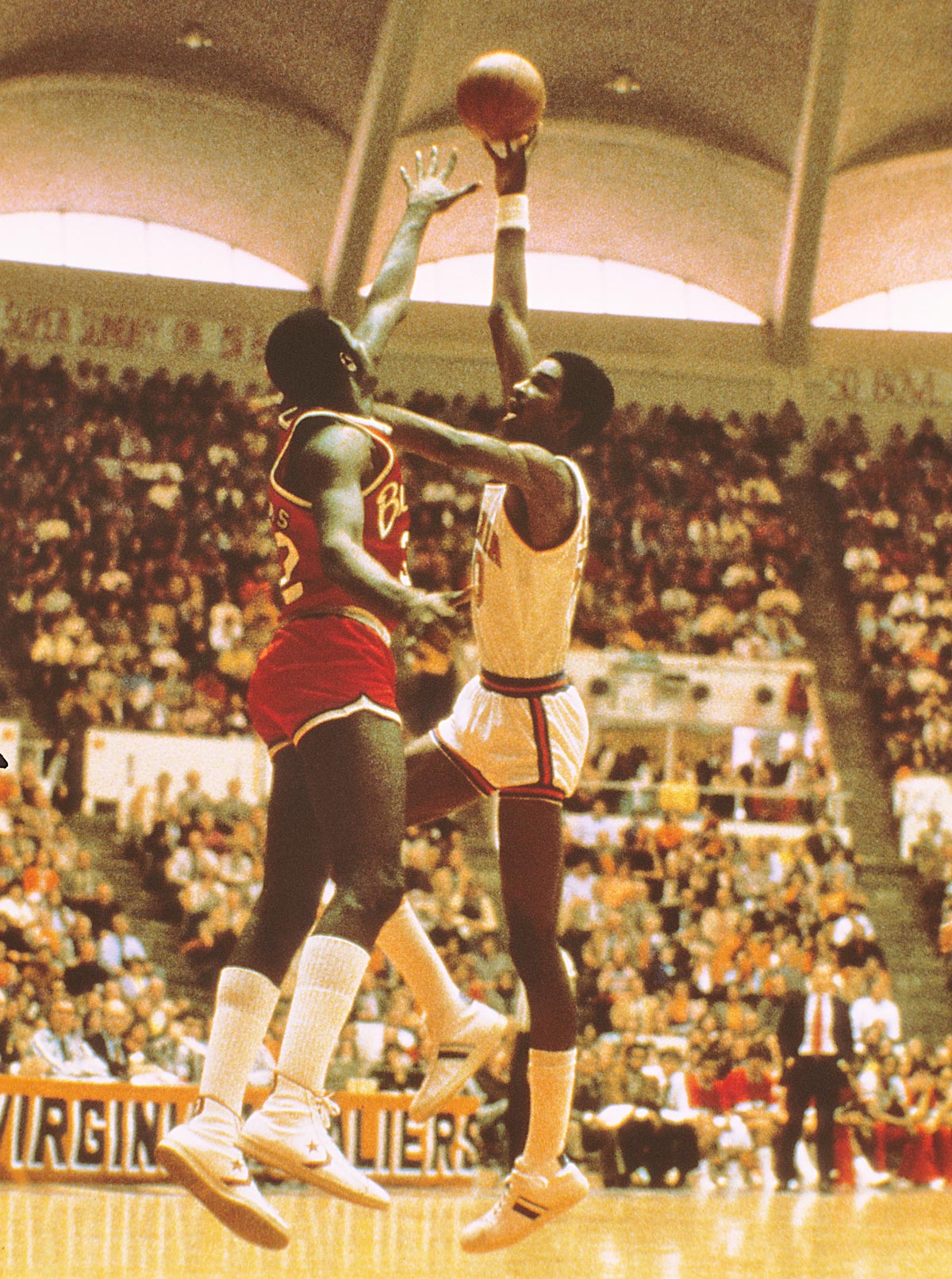

Of course, basketball took center court. An irreverent nickname, “The Pregnant Clam,” gave way to “Ralph’s House,” in honor of graceful, 7-foot-4 giant Ralph Sampson, the most prominent of many players who helped lead the Cavalier men’s team from mediocrity to the national spotlight. The Wahoo women, too, rose from an upstart program to national title contenders under Hall-of-Fame head coach Debbie Ryan.

In fact, basketball success eventually contributed to U-Hall’s demise, as demand for seats outstripped the supply, and the economics of big-time college athletics required more capacity and improved facilities. University Hall hosted its last basketball games in 2007, before the excitement moved across the street to the brand-new John Paul Jones Arena. It hosted a few more small events before increasing safety concerns forced its closure to the public.

Today, after months of demolition work, U-Hall is literally a shell of its former self, little more than a faded, stained roof and some massive supporting ribs. Even that will come down Saturday morning, when the remainder of the building is imploded. Once the rubble is cleared, the land it stood upon will become the site of grass practice fields – part of a major new vision that will transform the UVA athletics precinct.

All that will remain – besides some cool virtual recreations – are memories. Here are a few.

The ‘BP’ Era

Truth be told, the men’s basketball team that moved from Memorial Gymnasium to University Hall in 1965 was not very competitive. The Cavaliers had not posted a winning season since 1954.

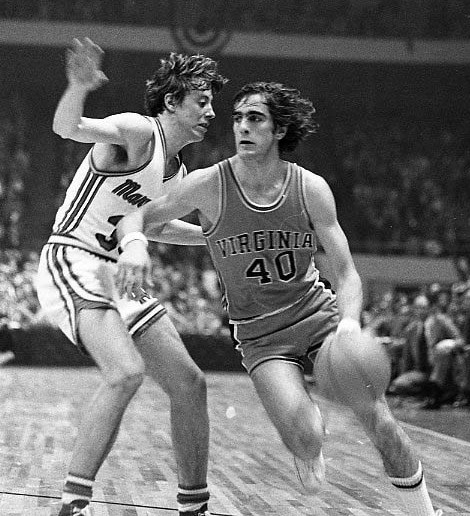

That all began to change in the fall of 1970, with the arrival of a second-year student, Barry Parkhill, on the Cavalier varsity (first-years were ineligible at the time). A sharpshooting guard, “BP” would lead the team in scoring in all three of his varsity seasons; he once dropped 51 points on a Division III team, Baldwin-Wallace, which still stands as the program’s single-game record.

Dan Plecker was a first-year student at the time. “We heard about a guy named Barry Parkhill who was supposed to be pretty good, so we started going to games,” he said.

Plecker and his friends were certainly not alone. The Parkhill-led Hoos were drawing some notice.

On Jan. 11, 1971, UVA celebrated its first-ever appearance in the Associated Press Top 20 rankings by upsetting the No. 2-ranked University of South Carolina, 50-49, on Parkhill’s buzzer-beating jumper – “a fade-away from the right baseline,” Plecker, now a Harrisonburg resident retired from the printing industry, said with assurance. “I can still see that shot. I had a piece of the net from that game.”

The stunning upset was the second of four wins in a span of eight days – all in a jam-packed University Hall – that pushed the Cavaliers’ record to 11-2.

“That place was loud,” said Parkhill, now an associate athletics director at UVA. “When we were there, winning was a novelty. It was new.”

Student seating at the time was first-come, first-served, and the student section would fill in the afternoon for an 8 o’clock tipoff, Parkhill recalled.

“I can remember waiting in line to get tickets,” Plecker said. “Then I remember they went to a lottery system because they didn’t have enough student seats.”

Parkhill’s favorite place in U-Hall? The playing floor – in the dark of night, honing his shooting stroke. “I spent many hours there at night. I just went in there all the time – I was just a typical gym rat.”

Though the 1970-71 season sputtered to a disappointing end, the program continued on its upward arc the following season, going 21-7 – the first 20-win season in 44 years. It all set the stage for the arrival of head coach Terry Holland, UVA’s first Atlantic Coast Conference Tournament championship in 1976, and the debut of a certain 7-foot-4 phenomenon from Harrisonburg.

‘Ralph’s House’

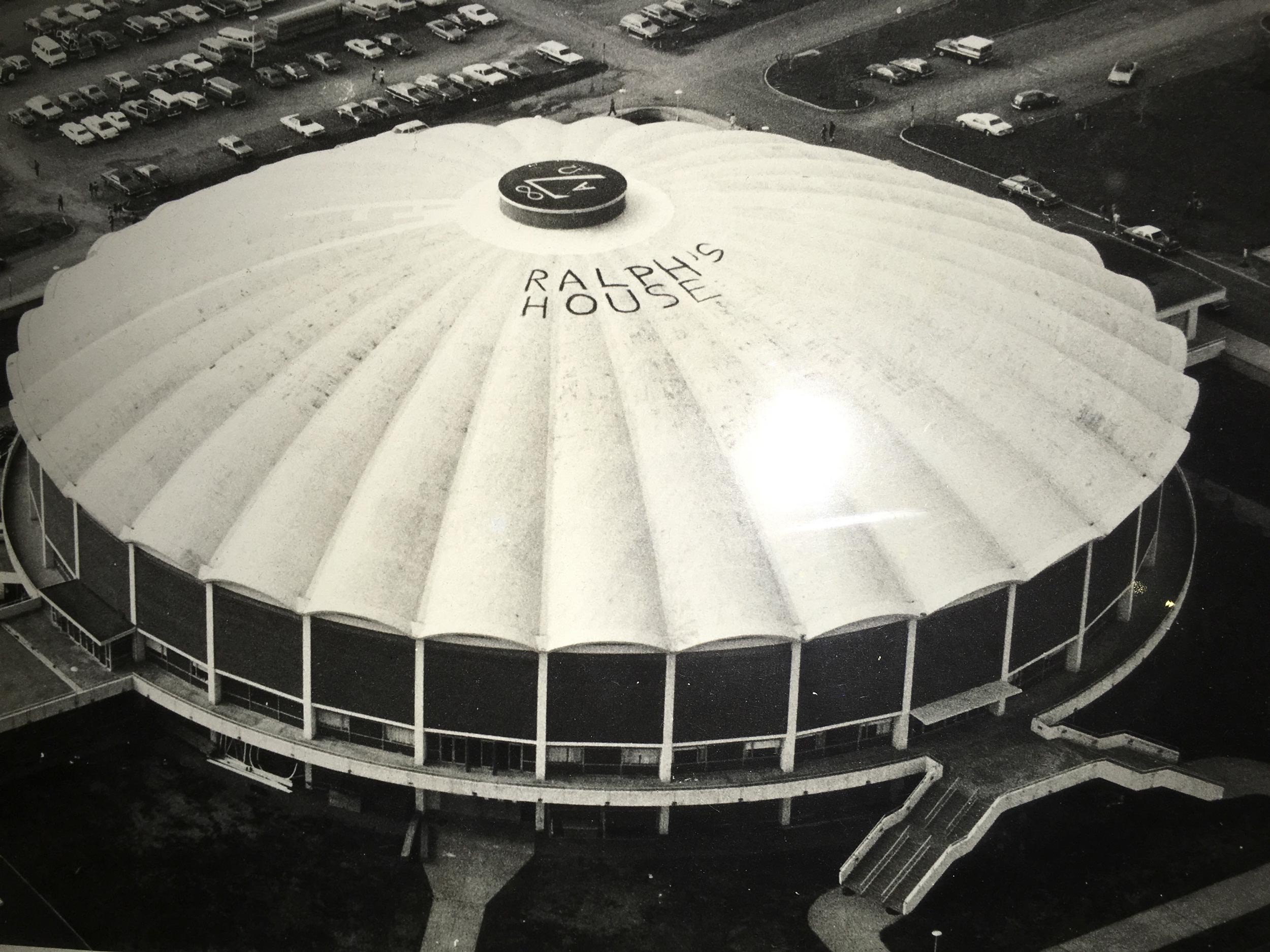

As Tom Hicks remembers it, the scheme was hatched in the Charlottesville home of Landon Birckhead, where Hicks was living after finishing his last season of basketball at UVA in the spring of 1979.

“After my senior season, we were sitting around the table one night, brainstorming about crazy things to do before we graduated,” Hicks said, naming as his accomplices Birckhead and fraternity brothers Bobby Edwards and Rusty Cleveland.

What they came up with was “a little outside the box,” Hicks admitted, and would live on in Cavalier lore.

Hicks came clean in a phone call this week. “I think the statute of limitations has expired,” he quipped.

The group was aware that Cavalier head basketball coach Terry Holland was in a fierce recruiting battle for Ralph Sampson, a gifted 7-foot-4 center from across the Blue Ridge Mountains in Harrisonburg. They also knew that Holland had arranged to helicopter Sampson in for his official recruiting visit.

Hicks was familiar with the innards of University Hall, including the catwalk under the giant roof, having explored it after practice one day. At the center of the roof, there was a padlocked hatch that led outside – key elements of the plan born around the Birckheads’ table.

Around 2:30 a.m. on the day of Sampson’s visit, Hicks, Edwards and Cleveland parked across Emmet Street from U-Hall and stole across the grass practice fields, carrying two backpacks filled with 30 to 35 cans of spray paint (paid for by Birckhead, Hicks recalled) and some tools, plus a key to the arena that Hicks had secured.

When they reached the door, they found it unlocked. “That set off some alarms with us, that people might have gotten wind of it,” Hicks said. They debated whether to continue before deciding to go ahead.

The catwalk swayed as they made their way to the center of the roof, Hicks said. Then they managed to defeat the padlock. “Like a submarine, we just popped the hatch, climbed out, and there we were, with a great view of Charlottesville,” he said.

The roof’s slope was gentler near the center, but got more precipitous toward the edges, so they stayed close to the hatch. They divided up the spray paint and the letters of their planned message, and went to work.

There was one close call. Just as a security truck rolled into the arena’s parking lots, one of the spray paint cans fell out of a backpack and clattered down the roof before clanging loudly against the concrete sidewalk below. Remarkably, the security guards never saw or heard it, Hicks said.

By dawn, the “artists” were done and retraced their steps back to the car. When they got home, they made one phone call, to alert the Charlottesville Daily Progress. (What good was a caper if no one knew about it?)

Hours later, when Sampson and Holland flew over University Hall, there were two words spray-painted boldly in black against the shining white roof: